SANJAYA BARU

Economics is a political science. In the 18th and 19th centuries the discipline was in fact known as ‘political economy’. The earliest economists were all focused on policy and politics and right into the middle of the 20th century they grappled with real-life problems. When political economy entered the ivory towers of academia it was reshaped by mathematics and statistics and became an increasingly esoteric discipline.

It was the economic crisis of the interwar years of the last century, the 1920s and 1930s, that elevated the status of economists from that of problem-solvers to that of social saviours. Robert Skidelsky, the historian and biographer of John Maynard Keynes, put it well in his biography of the ‘great saviour of capitalism’ when he said: “Keynes and his fellow economists viewed themselves as members of an activist intelligentsia, claiming a right of direction, vacated by the aristocracy and the clergy, by virtue of superior intellectual ability and expert knowledge of society. They saw themselves as the frontline of the army of progress.”

So, it is not surprising that so many want to know the views of professional economists on what I believe was an essentially political decision of Prime Minister Narendra Modi — the de/re-monetisation of `500 and `1,000 notes.

The fact that the de/re-monetisation decision has been defended in the media more by the government’s political spokespersons than its economic policymakers also suggests that the government views the decision and its consequences more in political terms than just economic ones. Perhaps it is just as well that the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India and the Chief Economic Advisor of the Government of India have stayed away from public debate, though much to the chagrin of bankers, financial analysts and economists.

The views of most economists, at any rate, appear divided along political lines. Thus, economists known for their Left-leaning views have all criticised the government. Most economists who have worked for Congress party governments have also criticised the decision. There are economists with other political affiliations whose views also reflect their political preferences, like Amit Mitra in West Bengal. Even if all their arguments are well-informed and important, most are bound to discount them for their political leanings.

Who, then, are the ‘objective’ and ‘politically neutral’ economists whose views on demonetisation/remonetisation one may regard as professional and politically unbiased? I cannot think of many and, in any case, I would not waste my time looking for them. That is not because I do not value their views, but because I believe we would be barking up the wrong tree.

Prime Minister Modi took a political call on the currency issue. He would certainly have been aware of the short- to medium-term problems it would create for most people. Perhaps he imagined that these costs would be less than what they are proving to be. After all, as I have said so often, Murphy’s Law works unfailingly in India. If something can go wrong, it will. So, one can charge Modi with having under-estimated the magnitude of the disruption to the economy, but not with being unaware of such disruption.

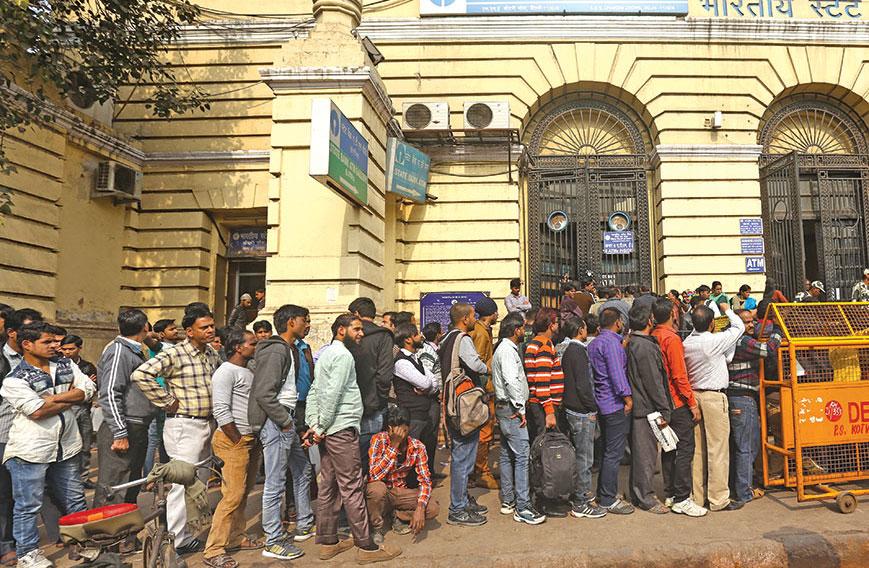

After all, within a day of his announcement, on 8 November, he asked for 50 days to restore normalcy. The decision was a post-dated cheque. Today’s pain for tomorrow’s gain. Interestingly, though, through the entire first month, upto 8 December, we have not had any reports of widespread public discontent. The Opposition political parties continue to try hard to mobilise public opinion against the Modi government but with little success so far. It remains to be seen if a tsunami-like wave of public anger will suddenly hit the government or if the government is able to restore near-normalcy in time, preventing such a political challenge to its popularity and authority.

In all this, what is interesting is the fact that the critics of the government continue to put forward economic arguments to defend their criticism of the government, while the government’s spokespersons keep changing the economic arguments in defence of the Prime Minister’s essentially political decision.

In the end, the politics of demonetisation will trump its economics. If Modi is able to convince the electorate that he has imposed this enormous burden on ordinary Indians in the interests of the country he will have won the political argument. On the other hand, if the political mood goes against the government, no amount of economic logic can save it.

There is one political gain that Modi has already secured from his monetary move. He has embedded himself firmly in the consciousness of almost every Indian across the length and breadth of the country. No other policy intervention since Independence has touched every citizen in the way this one has.

One can think of many politico-economic decisions that have had a wide social impact, like Indira Gandhi’s nationalisation of banks and P.V. Narasimha Rao’s termination of the licence-permit-quota raj. But even these major economic policy interventions did not have the kind of widespread social impact as Modi’s de/re-monetisation drive. Overnight, the name of the Prime Minister has become a household name across India.

In terms of branding and name recognition this is a coup that every marketing manager dreams of. Hate him or love him, you cannot ignore him. Having lodged himself in the mind of every voter, Modi has to now make sure that the voter will prefer him to someone else the next time she is at the hustings.

Viewed this way, the de/re-monetisation decision has profound consequences for the Delhi Darbar. For centuries the average Indian believed a Mughal ruler sat on the Delhi Darbar’s high throne. Even when the British ruled large parts of India, many did not realise that real power had slipped away from the occupier of the Red Fort. The British then built a huge new capital with enormous buildings to show one and all that they were now in power.

In free India generations have come to believe that the natural masters of the Delhi Darbar are members of the Nehru-Gandhi family. The rest were interlopers or pretenders. With one simple decision Prime Minister Modi has let it be known to citizens across the country that there is now a new ruler on the throne in the darbar. He has minted new currency for which you have to queue up. The Rupee is Dead! Long Live the Rupee!

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!