SANJAYA BARU

INDIA is a psephologist’s and electoral data miner’s delight. Not only does the country generate an enormous amount of electoral data but does so on a regular basis. It is, therefore, not surprising that almost every major political party now hires data miners and data analysts to generate political strategies. Some have even made a fortune in this start-up business. Despite the availability of more data and access to cleverer ways of processing and analyzing that data, election outcomes continue to baffle political analysts. The voter, like the consumer, is queen!

Indian election analysis has deployed several concepts such as swing vote, anti- and pro-incumbency vote and, a very Indian idea, Prannoy Roy and Ashok Lahiri’s ‘index of opposition unity’ (IOU). Interestingly, in the media analysis of the recent assembly elections, one mostly heard of the pro- and anti-incumbency factors and very little about the ‘index of opposition unity’. It would be useful to analyze the outcomes in Goa and Uttar Pradesh using the IOU concept. I would assume the score would have been very low.

Given the fact that we are once again in a political era in which there is one major national political party facing a plurality of opposition parties, the IOU concept would be once again relevant. This is the one big message for the Sonia Congress. It has been splitting the opposition vote in state after state, pretending to be the old single largest national party facing the new single national party. The fact is that the Sonia Congress is now just another regional party that has to work with other regional parties to keep the new single largest national party in check.

This is what the Sonia Congress was forced to come to terms with in Maharashtra where it is in coalition with Sharad Pawar’s Nationalist Congress Party and Uddhav Thackeray’s Shiv Sena. While the three partners did not come together before elections to exploit the IOU and win an election on their own in Maharashtra in 2019, their subsequent unity has allowed them to remain in office, keeping the BJP out.

The Sonia Congress could have made Mamata Banerjee’s victory in West Bengal in 2021 easier through a pre-election alliance with the Trinamool Congress. Or, maybe not. There is a view among several regional political parties that the Sonia Congress is at present more a political liability than an asset. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, many have argued that Akhilesh Yadav preferred to go it alone rather than seek an alliance with the Sonia Congress. While this may be true, it is possible to argue that if the Sonia Congress had more modest ambitions and had agreed to be a junior partner of the Samajwadi Party, the outcome may have been at best marginally different but a new political platform would have been crafted for the future.

It is still not clear what precisely was the Sonia Congress strategy for UP given the fact that the collapse in its vote base in the state had occurred as long back as in the 1985-1991 period. The Congress vote share has remained low and stable since 1991. With neither Rahul Gandhi nor Priyanka Gandhi Vadra offering themselves as potential state leaders for the party, what incentive was there for the Congress party voter to return to it?

Going forward to 2024, the ‘index of opposition unity’ will remain a critical factor in determining electoral outcomes. It is helpful to recall that, of the 16 Lok Sabha elections held after the first one of 1951, the outcome was pro-incumbent in the first four (1957-1971) and in the next eight general elections (1977-1998) it was pro-incumbent only once, in 1984, after Indira Gandhi’s assassination. In the subsequent five general elections (1999-2019), three (1999, 2009 and 2019) delivered pro-incumbent outcomes.

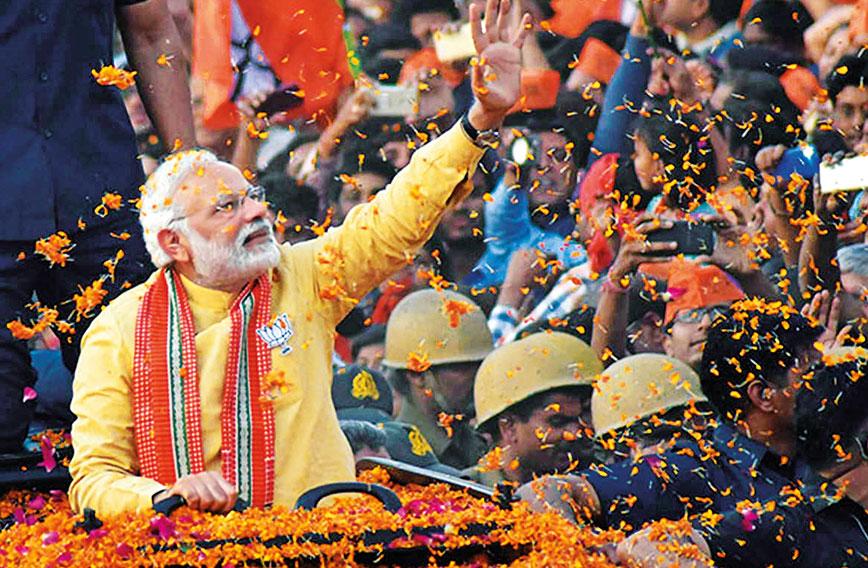

If the present BJP era is viewed as being similar to the Nehru era for the Congress, with successive pro-incumbent outcomes, then one should expect 2024 to go in Narendra Modi’s favour. On the other hand, if Modi’s style of governance and its economic outcomes are similar to the Indira Gandhi era, in which anti-incumbent outcomes far outnumbered pro-incumbent outcomes, then one should expect the 2024 outcome to be open to a real contestation.

What will make a difference to the 2024 outcome will be the ‘index of opposition unity’. Given that the period of 1951 to 1971 was largely pro-incumbent and 1977 to 2014 was largely anti-incumbent, the question is whether the pro-incumbency of 2019 in Modi’s favour will be sustained. Clearly, the ‘index of opposition unity’ can make all the difference.

However, if opposition unity has to bear fruit at the national level the Sonia Congress has to come to terms with the harsh realities of today. To begin with, it must cease to be the Sonia Congress and return to its earlier avatar of being at least the Indira Congress, if not the Indian National Congress. The Indira Congress was home to almost all the ex-Congress leaders of today who are at present in different political parties. If they have the courage, honesty and political commitment to offering an alternative to the ‘Hindu-Hindi’ nationalism of the BJP and are willing to work with a coalition of parties that are more committed to the values of the Constitution then it is still possible for a newly reinvented Congress to become the magnet for a new national coalition that can at least try to generate adequate anti-incumbency sentiment in time for 2024.

If, however, every non-BJP political party remains a one-leader, one-family-led party then the BJP will continue to record victories. Even though the BJP is also now a ‘one leader’ party, it has a national organization that is capable of delivering political victories across the country. The BJP’s challengers, with the sole exception of the Left parties, are all ‘one leader/one family’ parties, with weak party structures and organization. Little wonder then that Modi relentlessly targets parivarvaad and dynastic rule.

If the non-BJP parties have to blunt the edge of Modi’s parivarvaad attack then all regional party leaders — Sharad Pawar, Mamata Banerjee, Naveen Patnaik, M.K. Stalin, Uddhav Thackeray, Arvind Kejriwal, K. Chandrashekhar Rao, N. Chandrababu Naidu (or Y.S. Jaganmohan Reddy, depending on how the chips are likely to fall in Andhra Pradesh), the Yadav boys of UP and Bihar, the Abdullahs

of Kashmir and such like will have to come together, with Sonia Gandhi working with them, to engineer an electoral strategy that multiplies their individual strength.

This may sound bizarre but Indian politics is once again at a point when a range of political parties will have to come together, organizationally and ideologically, to challenge the dominance of the single big incumbent. In the 1960s, few viewed the communist parties as ever being in the position of kingmakers, nor did many regard Chaudhary Charan Singh as being of prime ministerial timbre. No one in the 1980s imagined a bunch of regional players would end the dominance of the Nehru-Gandhis.

If Sonia Gandhi restored power to her family it was by aligning with all such parties that had relentlessly fought the three prime ministers from her family. It is such out-of-the-box solutions that can help restore relevance to the Congress at a time when regional parties constitute the bulwark of a non-BJP platform. The problem for the Congress is that the rising stars of the non-BJP coalition are mostly anti-Congress parties — like the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) and the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS). However, if the likes of a Pawar and a Banerjee can bring Sonia, Rahul and Priyanka to work alongside, if not with, a Kejriwal, Patnaik, Rao, Reddy and Thackeray then a national alternative can potentially emerge. If not, Modi will get re-elected in 2024 and the pro-incumbent phase will get lengthened.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow at the United Service Institution of India

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!