SANJAYA BARU

A committee set up by the Central Election Commission of India has come out with a curious, if amusing, ruling. It has said that the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) should be amended to ensure that political parties release their manifesto “at least 72 hours before voting ends in the first phase of polls”. In other words, at least two days before voting is due. Given that campaigning, with its speeches, begins at least a month before voting, if not more, and that many political parties have started printing voluminous manifestos, it is worth asking if 48 hours is adequate time for a voter to read a manifesto and make up her mind as to who she will vote for.

But all this fuss assumes manifestos play a role in determining electoral outcomes. Sure, some key elements of a manifesto would. Major promises like farm loan waivers and temple construction would sway voters one way or another. These promises are repeatedly made in campaign speeches and their appearance in a manifesto lends weight to the promise. But, if a manifesto is about a few key promises, why produce a 50-page document? Some political parties have done that in the past.

Indeed, manifesto writers take themselves seriously. Political parties name a senior party leader as chairman of the manifesto committee to ensure that it is properly written and says all the necessary things. Given the time and effort that go into manifesto writing, any effort to make sure that it is read is a good thing. So kudos to the Election Commission for its ruling. It will at least be welcomed by those charged with the responsibility of writing a manifesto.

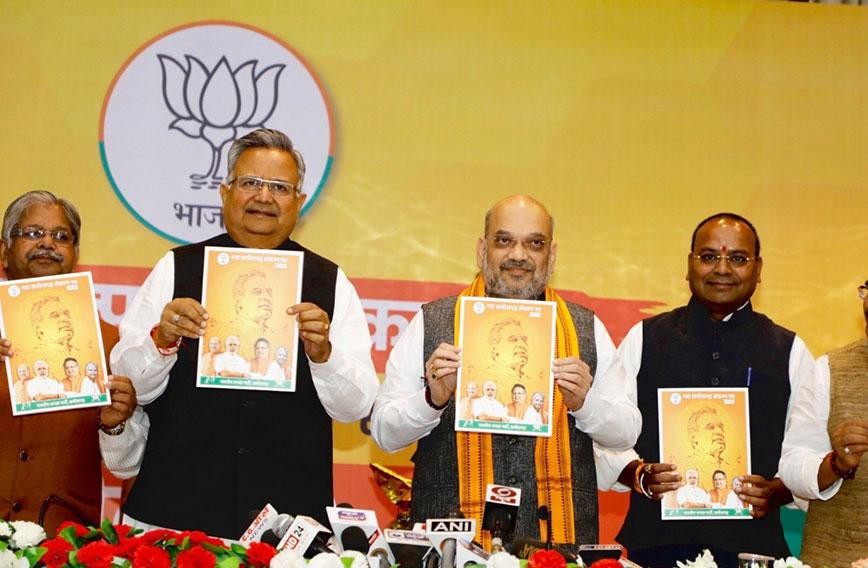

What has been the experience with election manifestos in the past? In assembly elections manifestos rarely matter, except with the Left Front parties. At the national level the major political parties — the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress — take manifestos seriously. Party members of repute and experience write these manifestos and the party president and head of government read the document carefully to make sure that no wild promises are being made.

In recent years, it was not a pre-election manifesto but a post-election ‘common minimum programme’ that really gained prominence in the actual running of a government. This was the famous National Common Minimum Programme (NCMP) of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) and the Left Front, drafted after the poll results to the 14th Lok Sabha (2004-09) were out. The NCMP was drafted initially by Bibek Debroy, now a member of the NITI Aayog in the Narendra Modi government and at that time an economist working closely with Dr Manmohan Singh, and finalised by Jairam Ramesh and Sitaram Yechury.

As prime minister, Manmohan Singh took the NCMP commitments very seriously. He created a unit in the PM’s office under a senior official that classified the NCMP into a hundred-odd specific commitments. For each commitment made, the relevant implementing ministry/agency was identified. The prime minister would chair a monthly review of the implementation of each promise made. The Left Front would demand a report from time to time to satisfy itself that the government was serious about the NCMP. Even after the Left Front withdrew support to the Manmohan Singh government, the PMO continued to monitor the implementation of the NCMP.

Interestingly, when the Left Front claimed that the India-US civil nuclear energy agreement was not a part of the NCMP and charged the PM with pursuing an agenda of his own, the NCMP was fished out to identify appropriate phraseology in the sections on foreign and economic policies that supported the view that the nuclear deal was very much a part of the NCMP.

Something similar happened with Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee when he chose to authorise the conduct of nuclear weapons tests and then declared India a nuclear weapons power. This was not an electoral commitment, claimed the BJP’s critics. The PMO promptly pulled out a stray sentence in the party’s election manifesto to argue that a commitment to go nuclear had in fact been made in the manifesto.

One reason why manifestos may play a lesser role at the assembly level and why even at the centre their relevance may have gone down is the fact that parliamentary elections have become presidential in the era of 24x7 television. Personalities seem to matter as much as policies. If a party gets the right mix between leadership personality and party manifesto, it can hope to score better — like K. Chandrashekar Rao and K.T. Rama Rao did in Telangana.

The reason the Election Commission had to come out with its observation on manifestos is because of the comically last-minute publication of manifestos during the recent assembly polls. Despite such cynicism, the fact is that major political parties are increasingly realising that the voter does judge a government by its ability to deliver on the promises made at the time of the elections. The Kamal Nath government in Bhopal had plans to set up a manifesto implementation committee, on the lines of the UPA’s NCMP, at least partly because it had come to the view that by April-May 2019 the government’s performance will be judged against promises made and that this will influence voter behaviour in the Lok Sabha elections.

It is also a fact that Prime Minister Modi’s standing has suffered from the fact that he is seen to have promised more and delivered less. Dr Singh’s motto used to be the opposite — promise less and deliver more. In the end, that approach delivers better electoral results.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer based in New Delhi

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!