Unionize MGNREGA for more impact

N.S. Bedi, Manisha K. & Ganesh Iyer, Andhra Pradesh

Our article is a response to two stories which were published in the June and July issues of Civil Society. First, your cover story, ‘Migrants in the mirror, where do we go from here?’ which had interviews with Chinmay Tumbe, Rajiv Khandelwal and K.R. Shyam Sundar. Secondly, your interview with Nikhil Dey, ‘MGNREGA money will run out with rising demand for work.’

We counter Nikhil Dey’s claim that MGNREGA was designed as a programme to be activated only in cases where households faced some form of shock or disaster. The design of MGNREGA is much stronger as it is an Act and, through the rights legislated in it, it could transform and reduce rural poverty. We also argue that the endorsement of bypassing the state government and having wage payments go directly from the Central government to the MGNREGA wage seeker is wrong. While good on paper, this design tips the checks and balances of the system by undermining the accountability of the state government to the rural poor. Through this, it is perpetuating and enabling fraud and wage payment delays.

In response to both articles, we argue that there is a simple solution to ensure that MGNREGA works as it is designed: To inform and organize the rural poor on their legislated rights under the employment guarantee law and to enable them and state governments to access these rights. This cannot happen without civil society taking up the role of helping to inform and organise the rural poor.

MGNREGA was legislated to enable rural labour to come out of poverty. Rural labour is not unemployed. It is underemployed. MGNREGA is giving them an additional 100 days of work at the minimum wage of Rs 205 (equal for men and women) plus for travel, water and sharpening of tools. The Below Poverty Line (BPL) yardstick in rural Andhra Pradesh is an annual income of Rs 52,000 for an average family of four. With a slightly higher MGNREGA wage of Rs 250 and 100 days of work, the rural poor could earn Rs 55,000 yearly and move above of poverty. This is so long as fraud, violation of rights and delayed payments do not take place.

But all this is still taking place daily, preventing poor households from being able to provide and feed their families. We are failing the rural poor.

Yet, there is a simple solution, which we have shown,that works.

But it is not going to be the National Electronic Fund Management System (NeFMS) system, as endorsed by Nikhil Dey. The NeFMS system, which started end 2017 with the Central government transferring wages directly into the bank accounts of wage seekers, bypassing the state government, is contradicted by field reality.

The biggest cause of violations of the rights of MGNREGA workers is NeFMS currently. It is, first of all, causing months of delay in wage payments to the rural poor. How can we deny wages to those who need it the most for the work they have done? Secondly, it is causing misuse of funds by splitting wage payments from material funds. Through this separation, the states are enabled to use material funds to undertake non-MGNREGA works.

In 2019-20, Andhra Pradesh’s MGNREGA budget was Rs 6,500 crores of which Rs 3,900 crores was for wages, and Rs 2,600 crores for materials and skilled labour (the Centre's share was Rs 1,850 crores and the state's share, Rs 750 crores). The YSR Congress transferred Rs 1,750 crores to 175 MLA constituencies to enable the MLAs to take up non-MGNREGA works.

To counter both articles, we must understand the design of MGNREGA. The article, ‘Money will run out with rising demand for work,’ has an inaccurate understanding that MGNREGA was legislated and "designed to help people in distressful situations such as drought or floods." The writer is confusing MGNREGA with NRES (National Rural Employment Scheme) which was an ineffective employment generation central government programme that was replaced by MGNREGA.

Unlike NRES, MGNREGA gives the right to rural labour to demand and receive guaranteed employment. It is important to understand why it was legislated, versus being created as a programme, as this shows the ability of this Act to help counter rural poverty if allowed to be implemented as designed.

Young India Project (YIP), an NGO, has been working with landless, marginal, and small peasants since 1972 in Anantapur district of Andhra Pradesh. From 1972 until 1983 we implemented programmes such as state bank funded farmers cooperatives, which included middle and large farmers, undertaking extension work. Our goal was to increase agricultural production.

In 1983, we decided to do an in-depth study on what impact our work had on landless and marginal peasants, as they are the poorest in the areas we were and are working in. Our study gave us two very eye-opening responses:

- The lands which the landless had been cultivating for generations had been registered illegally in the names of relatives and friends of big farmers.

- Over the years, work available to rural labour, landless and marginal landowners, had been going down annually because of mechanization and new cropping patterns to increase profits. This had reduced their wages to Rs 90 for men per day and Rs 50 for women per day -- basically to starvation wages. Rural labour was being reduced to abject poverty.

As a result of this study, we at YIP, asked them what would they like us to do for them. Their answer was first, help them get their lands back, and secondly, help them get more employment. They did not want handouts, they wanted to be able to provide for themselves.

As a result, YIP started forming Mandal unions with chapters in each gram panchayat to take up and support the rights and struggles of rural labour. One of the first rights we took up was their right to land. Over the next 20 years, our unions also took up house sites in the names of women, bonded labour rehabilitation, atrocities committed on Dalits and participation in Panchayati Raj elections under the amended Panchayat Raj Act of 1994.

In 1986, the unions began to address the second demand of the rural poor, which was access to additional employment. In January 1986, the unions started a campaign to demand "the legislation of right to work for rural labour."

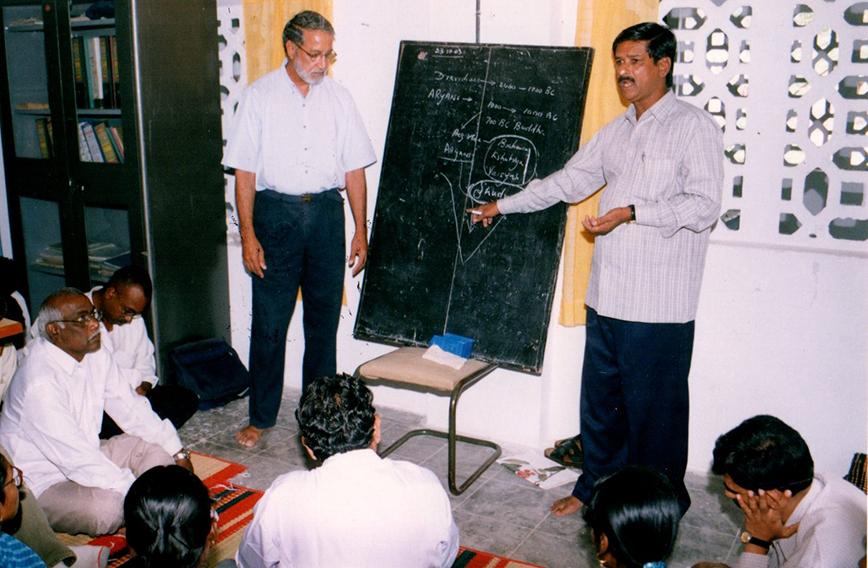

We organized a seminar on "the legislation of right to work for rural labour" in NIRD (National Institute of Rural Development), Hyderabad, with government funding. YIP invited seven prominent economists, including Prof N.Rath, Dr Dandekar, Dr S.S. Mehta and Dr Subbarao among others, as well as 40 NGOs from Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Odisha. At the end of the seminar, it was decided that NGOs would start a movement in each state to demand "legislation of the right to work for rural labour."

A delegation, headed by the president of YIP,N.S.Bedi, met the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, at his residence in 1987. This was made possible because Rajiv Gandhi and Bedi were old boys of Doon School. The PM committed that his government would legislate the "right to work for rural labour." He called up Prof.Hanumantha Rao, head of the Second National Commission on Labour, in the presence of the delegation and informed him that he had decided to accept the legislation proposed by the coalition and mandated that it should be included in the commission’s report.

In 1988, YIP president N.S. Bedi met Prof. Hanumantha Rao at the NIRD and submitted YIP's draft recommendation for the proposed legislation. These recommendations were adapted directly into the commission's report. The movement in Andhra Pradeshwas very successful because it was being conducted directly by the rural poor through the unions formed by YIP. It failed in all other states because the voices of the rural poor were not being heard as NGOs had not unionized rural labour to lead the movement themselves.

YIP unions sustained the movement for 20 years until the right to work was legislatedby Sonia Gandhi's government in 2005. Rajiv Gandhi's commitment had been honoured.

We must give full credit to Aruna Roy for her strong role in Sonia Gandhi's National Advisory Council (NAC) to get MGNREGA legislated.

It is important to understand that the legislation gave underemployed rural labour additional employment for 100 days at minimum wages to enable them to come out of poverty. In Andhra Pradesh, in case of drought, an additional 50 days are given.

By 2005, YIP was convinced that rights given to rural labour can only be demanded and received if they are informed, organised and enabled to do so. It is in this space that NGOs and their cadres can play a central role in making sure this happens.

This is especially important as MGNREGA is neither a scheme nor a programme. It is an Act. In his article, Nikhil Dey continuously refers to MGNREGA as a “programme" or "scheme", which it is not. As a legislated Act, it gives eight rights and four entitlements to rural labour. The crucial rights being the ability of a family to apply for a job card directly. Once they have a card, they are organised into a group. The group has the right to submit a written demand for work for a specified number of days. If work is not given within 15 days of their request, the government has to give each job card holder compensation for each day of delay. Importantly, the Act also clearly articulates that the government has to release wages within 15 days. If wages are delayed, the government has to pay compensation for each day of delay.

Each of these rights is critical in creating checks and balances that limit potential fraud. This can only work if households know each of their rights and are organised to demand them. This is the gap in the current system. Rural workers are neither informed nor organised. Hence they are at the mercy of a top down system and those who benefit from denying them these rights.

This gap can easily be addressed by civil society. If civil society, including NGOs, were to inform, organise and help the rural poor realise all the rights given to them under MGNREGA, the resulting voice of the rural poor would play a vital role in preventing fraud and violation of rights. This includes demanding compensation for work not released in time, or as currently being experienced, demanding compensation for delay in wage payments. The rural poor are the least able to cope with these delays. How do they feed their families as payments for their work are stuck in a bureaucratic system that seems to be benefiting the higher ups.

Yet, NGOs and civil society are not taking up this role. They are not ensuring that the rural poor are informed and organised to access one of the main Acts that could transform the level of poverty in rural India. One key reason is lack of funding -- there is no money in organising rural labour. Or maybe they feel this is political work and should be done by the left parties, who have never organised rural labour on issues identified by rural labour. In any case, due to this inaction by NGOs and left parties, rural labour is in a helpless position and is consequently at the mercy of governments officials in Andhra Pradesh and sarpanches in the states which are implementing MGNREGA through panchayats. While panchayats may have been elected democratically, they function under the control of local political leaders (the big landowners). This group holds power.

Divided households and their MGNREGA groups, who are often from the most vulnerable groups of society both economically and socially, cannot stand up to them. Is civil society and its NGOs going to sit on the fence and let that happen? Not YIP.

In September 2006, the Andhra Pradesh government asked us to do a social audit, which came about due to Aruna Roy and MKSS bringing in the RTI and social audit: one an Act and the other a monitoring system to expose fraud. We found extensive fraud in taluks by officials in collusion with local political leaders. In Gudibanda and Somandepalli taluks, the frauds committed added to lakhs.

As a result of the audit, we also found that workers did not know that MGNREGA was an Act that had given them many rights. Theythought it was just another government programme. In our report to the government, we recommended that to prevent fraud, job cardholders must be organized into groups and informed of their rights and how to access these rights. Organizations of job cardholders must be formed in each gram panchayat and each taluk.

In neither of the two stories is there any mention of informing and organizing MGNREGA workers to enable them to protect and enforce their rights. This is a major lacuna in both articles.

Andhra Pradesh took this path between 2010 and 2016. An NGO-government collaboration, APNA, was created to inform and organize the rural poor to access their rights under MGNREGA. This programme was originally piloted between 2008-2009 by YIP. The government paid for the training costs of the union mates. The Principal Secretary of Rural Development, Mr Raju attended a meeting with 600 representatives from 20 taluks unions on 22 September 2009 in Anantapur and was convinced that informing and organizing workers into taluks samakhyas and gram panchayat samakhyas was the only way to make MGNREGA demand-driven.

His successor,Mr Subramaniam, met N.S.Bedi in February 2010 and based on a consultation with YIP, he passed a government order creating the Andhra Pradesh NGO Alliance (APNA). APNA was a partnership between the state government and NGOs. The NGOs were made responsible for forming SSS (Srama Sakthi Sangam) groups and organizing them into gram panchayats and guiding them to protect and demand their rights.

The NGOs were allotted taluks and they appointed two Community Resource Persons (CRP) paid by the government to do the work. APNA was very successful. By 2014, 235 NGOs had joined APNA and they were covering 425 taluks out of 625 taluks in the state.

Then NIRD evaluated APNA from October to December 2016 and submitted a very positive report, calling Andhra Pradesh a pioneering state. In November 2014, YIP wrote an article on APNA and it was published by Civil Society, titled, ‘Andhra’s APNA job scheme.’

If APNA is restarted in Andhra Pradesh it will ensure that migrant workers returning to their villages are registered under MGNREGA, receive their job cards, form SSS groups, and demand and receive work. The additional funds needed to do this will have to be coughed up by the Centre. They have no choice. Migrant labour being a part of rural labour is covered by MGNREGA. It will be up to NGOs to ensure that this happens.

Unknown to Nikhil Dey, MGNREGA has been evaluated in Andhra Pradesh. But, despite the positive report of NIRD under TDP, APNA was discontinued in 2017, and fraud, violation of rights restarted. YIP is struggling to convince the YSR Congress to revive APNA. Without informed organizations of MGNREGA workers, MGNREGA is going to fail. The writing on the wall is clear but the government and NGOs refuse to read it.

Contact: [email protected]

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!