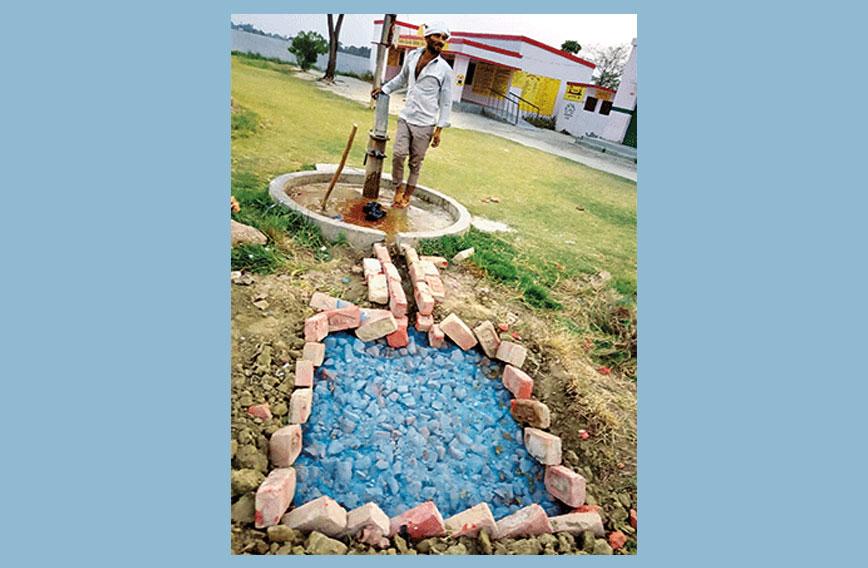

A village soak pit in Popraich block of Gorakhpur district

Gorakhpur digs pits to keep diseases at bay

Sandeep A. Chavan, Gorakhpur

One day Dharmendra, a field worker with Project Prayaas, a Tata Trusts initiative, spotted Babulal, a local resident, emptying waste water from a pit in front of his house in a village in Pipraich block of Gorakhpur district in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The pit was full of foul-smelling water with mosquitoes rampantly breeding in it.

Obviously, Babulal wasn’t happy emptying his pit. But he had to. The pit was full of dirty water coming out from his house. He had to empty it manually before it overflowed.

What he needed was a soak pit or a Swachh Sokhta Gaddha. Dharmendra offered to help but how was he to go about doing it?

Pipraich block is in the Terai region, close to the Nepal border. It is infamous for repeated epidemics of diseases including encephalitis and malaria. Nearly every other year, children die of Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES), a deadly disease.

A key factor for the spread of encephalitis is the poor state of hygiene and sanitation in Gorakhpur district. Project Prayaas is implementing community-based health promotion strategies in Pipraich block and Uska Bazaar in Siddharth Nagar district.

Under the Swachh Bharat Mission people are either thinking about making toilets or have already constructed them. But the drainage system is a picture of neglect. There is either no drainage system or drains are blocked. The topography of the area encourages mosquito breeding sites.

The Prayaas team carried out a social mapping exercise with villagers and identified all the blocked surface drainage channels and waterlogging spots around hamlets and households. These visual maps were reviewed by the community and a dialogue was started to identify simple solutions like soak pits.

Soak pits are not an innovation. But they are not popular and their value is underrated. People were under the impression that such pits were expensive and could only be constructed with government schemes.

The Prayaas team decided to construct a soak pit near a village school with low-cost technology so that villagers could see for themselves that making a soak pit was easy and inexpensive.

The team received technical guidance from Col (Dr) M.P. Cariappa, a public health specialist and an adviser with the Tata Trusts.

Cariappa broke down the method of making a soak pit into four simple steps called Triple Four. First, dig an unlined pit four feet deep, four feet long and four feet wide. Second, fill it with brick rubble and not stones. Brick rubble absorbs water easily, unlike new bricks. Third, the surface of the pit is to be covered with an old mosquito net or a mesh to keep out leaves and debris. The surface margins of the pit must be lined with brick pieces to give the boundary a neat appearance. Finally, the outlet of the hand pump roundel (or from wherever wastewater is draining off according to the natural gradient) is connected to this soak pit at one end.

A similar soak pit named the Swachh Sokhta Gaddha was made in a village school compound, draining wastewater from a public hand pump so that children and passers-by could observe its benefits.

Dharmendra explained to Babulal how an inexpensive soak pit, using locally available material, could be easily constructed. Babulal would only have to pay for brick rubble and it would take just a couple of hours to make, using ordinary implements. Once Babulal made his soak pit, other villagers saw it and asked for technical guidance to make similar soak pits for their homes.

Apart from technical inputs, the Prayaas team did not contribute anything to construct these pits. Individual families financed their own pits or accessed funds from the gram pradhan. Pits around public facilities were fully funded with panchayati raj funds up to `3,000 per pit. Around `600 was spent on labour and a small sum on brick rubble if it needed to be bought. If brick rubble was available, the cost of the soak pit was minimal.

There is provision under MGNREGA for construction of soak wells or pucca soak pits. Different villages have come up with different models.

It is to be noted that the Prayaas soak pit is not intended for sewage or for large quantities of sullage or rainwater.

It is essentially for domestic drainage requirement and for low-usage public hand pumps.

Maintenance of these soak pits is quite simple. Lallan Prasad, the block coordinator of Team Prayaas, explained: “Every month, the brick rubble should be removed and dried for a day. Leaves and debris inside the pit should be emptied.”

“During the monsoon, it is best to just leave the pit as it is and do the cleaning and drying after the rains are over on any sunny day,” said Cariappa.

The gram pradhan takes on the responsibility of maintaining soak pits in public spaces. Most villages have youth groups who clean up this facility. One gram pradhan said he paid labour charges from government funds to maintain soak pits in public areas.

Another option would be to pay maintenance-related labour charges through the Village Health and Sanitation Committee funds or MGNREGA funds by putting up a labour cost.

“Soak pit technology is a key component in reducing vector-borne diseases like dengue and malaria. Actually, this is an age-old practice that people seem to have forgotten,” explained Indrajeet Kumar, Project Officer of Project Prayaas in Gorakhpur.

Team Prayaas has also engaged with the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme team at the block and district level. The objective is to play a catalytic role in implementing vector control strategies through the public health system with community participation. The strategy includes source reduction, use of protective measures such as medicated bed nets, larvicidal measures and so on, to bring down the incidence of vector-borne diseases drastically.

Sandeep A. Chavan is a programme officer for health initiatives with the Tata Trusts. He works in eastern Uttar Pradesh with the Prayaas team.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!