KIRAN KARNIK

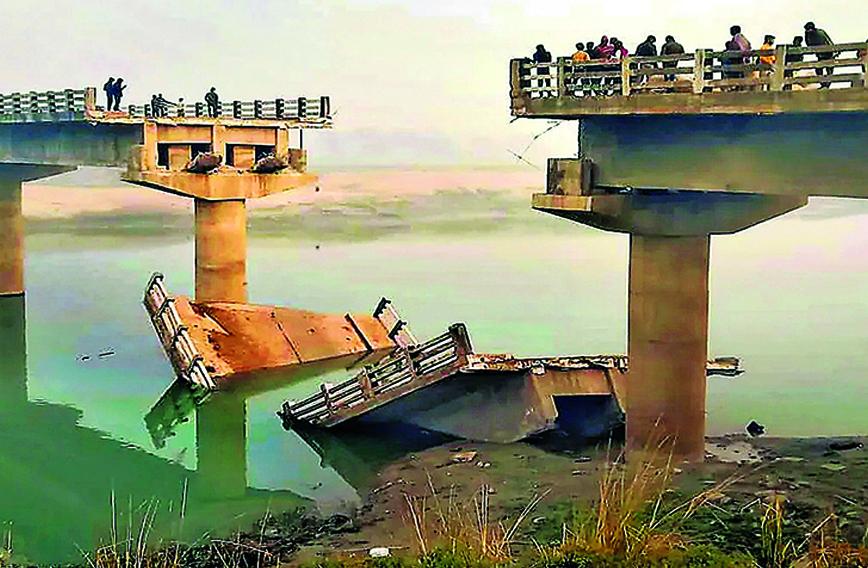

AT the recent Conference of Governors, Prime Minister Narendra Modi urged governors to serve as “an effective bridge between the Centre and the state”. Unfortunately, it seems that these have been built by the contractors who specialized in self-destruct bridges in Bihar! Delhi’s “broken bridge” problems seemed unique, an aberration, caused mainly by the complexity of being a state but not quite, and also the lack of clarity about division of powers. As court battles continue and new laws further erode the powers of the elected government, citizens pay the price.

Now, many other states too are amidst governor-government battles. It seems every “opposition party” state is embroiled in a controversy vis-à-vis Centre-appointed governors. Increasingly, it is evident that these disputes are political battles and are affecting overall Centre-state relations. These differences, and the blame game of mutual finger-pointing, have resulted in no accountability, no monitoring, and inefficient execution. The full force of the negative impact is felt by common people in their daily lives.

In cities and towns, civic services have broken down. Flooded streets, water shortages, power outages, sewage overflows, traffic jams, unbreathable air, lawlessness: these and other problems plague us. The never-discussed devolution of power and funds to the third formal level of government (local bodies/panchayats) and the lack of decentralization is a major factor contributing to this sorry state. Exacerbating this is chaotic structuring of local responsibilities. With multiple agencies often involved in delivering a service, it becomes easy to play the blame-shifting game and to avoid accountability.

The justice system is a major pillar of governance, but is now as broken as the Centre (governor)-state relationship. Sadly, the police are seen as extensions of those with money or power, serving as an appendage of the government and the parties in office. Between them and the courts, they have ensured that the process is the punishment. FIRs are filed at the drop of a hat; arrests are immediate, except for the powerful; jail rather than bail is the norm, despite pious statements by the Supreme Court; and trials go on forever, with adjournments as frequent as ads in IPL cricket matches. A wide and ever-growing number of laws allows arrests and long detentions with no recourse, thumbing their nose at concepts such as “innocent till proven guilty”. Intended as a deterrent for terrorists, these draconian laws have over the decades steadily filled the rule book, with their use becoming ever more frequent with wildly wide interpretations of “anti-national activities”. All political parties, when in power (whether at Centre or state) are complicit in their enactment and use (or misuse).

Numbers are a poor indicator of the impact on individuals, but the fact that 76 percent of those in jail (figures available for 2022) are undertrials — not convicts — is a telling statistic. Despite all the judicial pronouncements you read — from the Chief Justice of India (CJI) downwards — this figure has actually increased, from 70 percent in 2018. More significant — 11,000 have been in jail for five or more years, a doubling from 5,000 four years earlier.

A recent case from Delhi epitomizes the situation better than figures. A man driving his vehicle at 20 km per hour was arrested and kept in jail for four days, before getting bail, but the case against him apparently still stands. His crime: the water from the flooded street entered a basement because of the waves caused by his car, sadly drowning three students trapped there. While the court made scathing observations (“luckily you have not challaned the water”) and expressed surprise that no official had yet been held accountable for the flooding, it did not follow up by punishing the police for the frivolous FIR and arrest. Even Kafka could not take absurdity to this level.

Another example: Gurugram, along with the rest of the NCR (National Capital Region) and most other cities, has unbreathable, near-poisonous air. At the same time, thousands of trees — the best natural air-purifiers — are being cut with the permission or connivance of officials. While it is reported that the millennium city is consuming 240 percent of its water recharge, the government has decided that only 75 of the 5,000-plus acres of the Najafgarh wetland/jheel are worth conserving (the rest, presumably, can be sold to real estate developers). The same government continues to fight cases to allow “development” in the protected Aravalis. Just further evidence of a dysfunctional, citizen-unfriendly governance system.

What is noted above is indicative not only of the problems of poor governance, but also of correctives needed. Key amongst these are decentralization and devolution. Not only more power to the states, but to local authorities (the third tier of governance).

Looking ahead, one also foresees:

- The institution of governor, a hangover from colonial times, being altogether scrapped. In rare and very exceptional cases (ideally, to be approved by the Supreme Court), the Centre can appoint an administrator (members of political parties/organizations will be barred) for a limited period, till a new government is in place.

- Drastic reforms in the judiciary and police, along with independent oversight of regulatory agencies, so as to ensure their independence.

- More and smaller states with greater devolution; city mayors or CEOs with powers similar to a chief minister within their area, and bearing full responsibility for the smooth functioning of the city or panchayat.

- Single agencies with full responsibility for a complete task (e.g., sewerage, or road maintenance, or waste disposal), with no scope for buck-passing.

- Mandatory social audits of citizen services by recognized CSOs or professional agencies, along the lines of the statutory financial audit.

- All constraining amendments to the RTI Act scrapped to ensure that citizens have easy access to all information, thereby improving accountability.

- Grievance agencies with teeth, at various levels.

These changes are both necessary and inevitable for the country to fulfil its ambitions and for citizens to have a better life.

Kiran Karnik is a public policy analyst and author. His most recent book is ‘Decisive Decade: India 2030, Gazelle or Hippo’

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!