Street power has its limits

Civil Society News, New Delhi

Two months after the Union government appointed a committee of five ministers and five activists chosen by Anna Hazare to draft a bill on the institution of a Lokpal to fight corruption, deep differences persisted on what powers should be bestowed on such an ombudsman.

The committee was given a 30 June deadline. But till 20 June it could make little progress on substantive issues. It was agreed to disagree and put up to the Union Cabinet a draft bill with the views of both sides. The government on its part sought an all-party meeting. And Hazare threatened to go on one of his hunger-strikes again if Parliament does not produce a law by 15 August.

But by now thinking people were somewhat weary of such developments. Several questions presented themselves: Is the use of random street power the way to finding solutions to national issues? Did the Hazare group really represent civil society or had many other points of view been left out? Should an arbitrarily chosen committee have been drafting a complex law or should there have been a wider, more inclusive debate with buy-ins from different power centres and shades of opinion?

An agitation which had seemed to work so successfully at Jantar Mantar sputtered when it came to consultation and debate. The Hazare group - consisting of Arvind Kejriwal, Prashant Bhushan, his father Shanti Bhushan and Santosh Hedge - didn't just have problems with the government. The group's methods and its definition of a hugely empowered Lokpal were not endorsed by a large number of well-intentioned people either.

The result was that the key sticking points remained:

- Should the Prime Minister come under the purview of the Lokpal?

- Should the higher judiciary come under the purview of the Lokpal?

- Would the Hazare group’s demand of an elaborate investigative machinery adding up to 15,000 people, including a vigilance officer in every district of the country to report corruption, be a workable mechanism?

GRANDSTANDING

The UPA government has to take its share of the blame for the spread of corruption. But there is concern that civil society had been trivialised by demanding instant laws on matters of national concern and seeking to dictate terms to Parliament. The Hazare group wants the Lokpal Bill passed by 16 August. It is felt that the role of civil society is to suggest and influence and be the space in which more voices can be heard. It cannot seek to replace the political class much less Parliament itself.

Any number of ex-judges, lawyers and bureaucrats known for their integrity felt that the Hazare group's suggestions involved changes in the Indian Constitution that would not deliver results and may even do a lot of harm because they sought to disturb the current framework without adequate discussion.

The National Campaign for the People's Right to Information (NCPRI) is drafting a Lokpal Bill. The NCPRI sees the Lokpal dealing with grand corruption. But for the rest it is looking at a basket of measures that include judicial accountability, protection of whistleblowers and so on. The idea is to create processes which can deal with corruption at various levels by improving existing institutions.

But with the Hazare group holding centrestage and the media hoping to cash in on middle-class sentiments, there has been little room for other voices.

It also didn't go down well that members of the Hazare group berated Parliament and used intemperate language against the government and its ministers. It made many people feel that democracy itself was being dented by such an agitation. After all, the bill would have to be passed by elected representatives in Parliament. The support of the political class was important, particularly in the states.

As expected, an efficient and honest chief minister, Nitish Kumar in Bihar, refused to be part of rushing through a law. Mayawati in Uttar Pradesh told the campaigners to get elected first and then implement their ideas. Sheila Dikshit in Delhi said there was no need for a Lokpal. It would be better to strengthen existing institutions.

CONSTITUENCY MATTERS

Part of the problem seemed to be the Hazare group's lack of a well-defined and demanding constituency. Corruption affects everyone. But the Hazare group's support has been from the middle-class, film stars and so on - people who make whimsical choices and have little staying power. There was also support from godmen, the RSS and BJP front organisations. However, none of these elements made up a committed constituency. They either had instructions to be present or were there to enjoy the tamasha.

Ashok Chaudhury of the National Forum of Forest People and Forest Workers (NFFPFW) says the manner in which activists negotiate is determined by the constituency they represent. Activists working with marginalised groups don't have the luxury of returning to their constituency empty handed. The people they represent, who don't have access to health, education, food, jobs or even basic dignity place their faith in them, expect them to at least bring them some relief from Delhi. For them it's a question of survival.

"When we meet the government it is to achieve results because our constituency wants us to come back with something. Hazare and his followers have no real constituency except a vacillating middle-class and upper middle-class. They don't have to show results," says Chaudhury.

Chaudhury, who worked hard to get the historic Scheduled Tribes and Other Forest Workers (Right to Forests) Act, 2006, passed, says negotiations require give and take. There is a need to sit and talk. It is not about confrontation. "When we go to Jantar Mantar in Delhi it is come to an understanding and not to confront and belittle the government," he says. "When you call everyone, including the Prime Minister corrupt, what space have you left for negotiations."

The NFFPFW made innumerable presentations to Parliamentarians, lobbied with every political party big and small and did whatever it took to convince them about their draft law which would give land and community forest rights to tribals and forest people. It was not easy. There were powerful interests, like the wildlife lobby and the forest department bureaucracy, working against them.

Ravi Chopra of the People's Science Institute says: "Consultations should take place at the widest feasible level. No one likes to take to the streets. But governments are sometimes so obdurate and unwilling to listen that one is forced to do so. However, convincing people is the critical test."

Chopra played an important role in the campaign that led to the dismantling of dams on the Ganga. Elderly Dr G.D. Agarwal, a venerable environmental scientist, had to go on a hungerstrike during that campaign to make the government take note of the damage the dams would do.

But the hungerstrike would have been of little use if serious efforts hadn't been made to engage with the government and place scientific evidence against the dams before it. Solid research plays an important part in convincing the government.

The central law on right to information (RTI) came out of a long process. Activists examined the working of RTI in the states, collected evidence from the grassroots. The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) went through a similar exercise.

Nikhil Dey of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) says: "Nothing is open and shut. You can't cut back on the consultation process. Laws like the ones on right to information and rural employment were passed with a lot of give and take. As activists we didn't always have our way."

Kavita Srivastava, general secretary of the People's Union for Civil Liberties and a right to food activist says: "What the media finds sexy gets projected. Anna Hazare's fast gets coverage but there have been so many fasts which have been ignored. In 2007 when 200,000 people gathered in Jagdalpur to protest against Salwa Judum, there was no one to cover them."

"The agitation against corruption has caught the mood of the country, but its leaders have not succeeded in going beyond that. Corruption has to be dealt with at various levels. There can't be any single solution to it like having a Lokpal. Nor can there be only one point of view. The fight against corruption has to be seen in the larger context of globalisation and privatisation."

Like Chaudhury, she believes the constituency makes a difference: "For the poor, corruption is a right to life issue. But for the middle-class it is not. It is important to have the support of the middle-class on an issue. I work with the middle-class. But the middle-class has to also realise that complex issues don't have simplistic solutions. There is a lot of corruption within the middle-class."

She believes that street power is important. Without it no one listens to you. "But it is simultaneously necessary to create the space for dialogue and negotiation. In the right to food movement we have found that it is not enough to agitate. It is as important to meet MPs and ministers and get one's point of view across."

Ravi Agarwal of Toxics Links says: "There is obviously great anger amongst people about a sense of injustice of having been betrayed by the political establishment for years on end. Those guilty of corruption have hardly ever been punished and carry on regardless. However changing this situation needs a cool head and rational thinking, and not mere television grandstanding."

"No one disagrees with the need for systemic reform to reduce corruption. The question is how," says Agarwal. "Holding a government to ransom, especially one which we have elected as ours, cannot be the way forward. Tinkering with basic Constitutional checks and balances needs great caution else the consequences can be far too serious. We must broaden the Lokpal debate to include the variety of opinions and expertise which already exists on the issue. It is the only way."

A.V. Balasubramanian of the Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems in Chennai agrees. He says one of India's strengths is its political stability - that elections are free and fair and held regularly. It is this stability which has created space for civil society groups and they would do well to look at other countries in the Asian region and value what India has.

"We know that if we don't like a government we can remove it," he says. "Nevertheless street power is justified. It is merely a means of applying pressure so as to bring something to the notice of the government and influence policy. Companies and industry lobbies use advertising to the same end."

LACK OF DIALOGUE

Civil society gets its legitimacy from the issues it raises. But it also has to accommodate different shades of opinion and be pragmatic about the ways in which it seeks to connect.

Members of Hazare's group, like Kejriwal and Prashant Bhushan, have instead delivered hammer blow after hammer blow. They have been strident in their views and insisted on their version of the Lokpal Bill.

At a convention held in Delhi by The Foundation for Media Professionals to hear activists' views on the Lokpal, Kejriwal brought along his supporters who cheered as he spoke and left with him even before activists with another point of view had spoken.

However, several substantial points were made. On bringing the judiciary under the Lokpal, Justice AP Shah said the office of ombudsman exists in 129 countries but the judiciary does not come under it. He said it was unfair to say the judiciary is wracked with corruption. Action against those responsible for the 2G scam has been taken by the Supreme Court. Many notable orders had been issued in other cases too. The judiciary was also sensitive to the issue of corruption in its ranks. He agreed that the judiciary needs to be made accountable but not to the Lokpal. It should be accountable to itself.

He felt that the Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill pending in Parliament needed to be strengthened, but bringing the judiciary under the Lokpal was unwise.

Usha Ramanathan, the civil rights lawyer, said India's democracy has done well due to a clear separation of powers between the executive, legislature and judiciary. This arrangement should not be tampered with in any way. There was no absolute certainty that the Lokpal would be completely insulated from the executive or the legislature so it is safer to leave the judiciary out of its purview.

The Hazare group proposes that the judiciary could investigate complaints against the Lokpal. And the Lokpal could order an FIR to be filed against a judge accused of corruption. But Justice Shah said this circuitous arrangement could create a conflict of interest - supposing a judge was called upon to investigate the Lokpal who in turn was giving orders to investigate the very same judge?

On putting the Prime Minister under the Lokpal there has been rough consensus, but this is a sensitive issue. Justice Shah suggested a two-third majority of members in the Lokpal decide if an inquiry should be initiated. The Prime Minister would not need to resign and the President of India should be the person who can give sanction for an investigation. There are other views as well.

The Hazare group wants a Lokpal with 11 people with impeccable reputations found through a search committee. The Lokpal will enforce the Prevention of Corruption Act and have a nation wide staff strength of 15,000. At district level there would be a Vigilance Officer to act against complaints of corruption. Every department will have a Citizens' Charter and if work is not done within a specified time, it will be assumed delays were due to corruption.

Former bureaucrat, Satyananda Mishra, pointed out that it is difficult to get 11 people of unimpeachable character so finding 15,000 people would be even tougher. Who would see to it that this entire staff did their jobs honestly?

The same ills which beset existing institutions could befall this one, it was felt. At the grassroots people face problems in getting their entitlements or may be a ration card or passport. Nobody goes to the police because they are corrupt and they have a stick. "Now we are saying lets give another body a bigger stick and it will sort things out. Will it?" asked Nikhil Dey.

Interview:

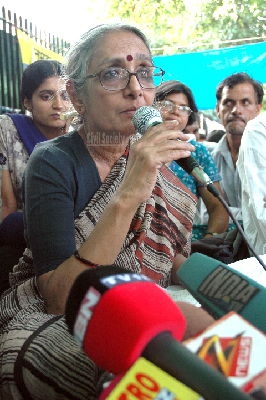

'Let Lokpal deal with grand corruption'

Aruna Roy has been one of the respected social leaders who believes that a strong Lokpal is needed but overburdening the Lokpal with so many responsibilities has serious downsides. A founder member of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS), she has been an important voice in the campaign for the right to information and employment guarantee. Roy is a member of the National Advisory Council (NAC). She spoke to Civil Society on the need for systemic improvements to deal with corruption at all levels.

What are your key points of difference with the Jan Lokpal Bill mooted by the Anna Hazare group?

We support the need for a strong, effective and comprehensive legislation to tackle corruption, misgovernance, and are therefore basically in agreement with the major goals of the draft Jan Lokpal Bill. However, we believe that the Lokpal should be an independent body that has a focused and actionable mandate of dealing with grand corruption, and corruption in the highest echelons of power. This is an urgent need because of the number and scale of scams that are tumbling out, and there is complete impunity for those at the top. Of course there are problems of accountability at almost every level of government. Our major concern is that the Jan Lokpal Bill seeks to place too much power and responsibility in one institution.

Expanding the mandate of the Lokpal to include grievances, misconduct, judicial accountability etc will over burden the Lokpal. In mandating the Lokpal to correct everything, it may end up doing nothing effectively. Equally important, this would concentrate too much power in the Lokpal, not be subject to adequate checks and balances, and might violate the basic constitutional principle of separation of powers.

We felt that it was more useful for us to examine the possibilities of formulating a basket of measures that would create separate institutions to deal with the lack of effective oversight and accountability in each sector. Protection for whistleblowers, misconduct, reform of the CVC, grievance redress, and grand and petty corruption have thrown up unique challenges. Each sector needs its own framework that is appropriate, adequately empowered, independent, and is eventually accountable to the people. That is why we proposed to work on each of these issues separately, while building a campaign for them to come into effect simultaneously.

Do you think the Lokpal can resolve the problem of corruption from the grassroots upwards?

The current framework of the Lokpal is a top-down structure not just for fighting corruption but also for redress of grievances, providing whistleblower protection and ensuring judicial accountability. This framework is suitable for investigating corruption at the highest levels, but cannot effectively resolve problems at the grassroots. Even in grievances, the role of the people affected is that of mere complainants without any forum for participation for resolution. For instance, grievances in rural areas stem from a range of issues like uncooperative administration, elite capture of government schemes/programmes, faulty implementation, infrastructural deficits etc. Such grievances can be best dealt with by improving the departmental response to these grievances and by infusing transparency and accountability in their functioning. While we feel that there is a need for an independent authority that deals with the outcomes of people's monitoring and complaints, we don't believe that the Lokpal Bill is the best suited legal instrument to do so. Bottom up systemic improvements are needed for effective grievances redress. We feel that the law needs to incorporate processes like social audit, which are reflective of a bottom-up, and people-centred approach to fighting corruption and mal-administration.

Are you in favour of putting up an alternative draft, which expresses your concerns?

The NCPRI is developing a framework and basic principles for any law/s that seek to address these multiple concerns. This set of principles and framework will be the base for open discussion and public consultations with people and subject matter experts in the coming months.

How would you like to define civil society in India and what should its role in pre-legislative consultation be?

"Civil society" is amorphous, and the term is used at will to denote any institution or anyone outside the State. There is a risk of assuming universal legitimacy, and subsuming a plurality of views with the arbitrary use of such nomenclature.

The concept needs to be unpacked. The claim of one group or the other to represent civil society becomes dubious and therefore suspect. There will and should be a plurality of views and differing groups in the large population outside the State. It is a sign of a healthy democracy.

Civil society can help ensure that debates take place in the true spirit of democracy, where differing views are aired, respected, and incorporated within the larger picture. Civil society must in fact ensure that people do not fight shy of airing their views. The politics of ideas extends beyond political parties, and civil society must not depoliticize the wider politics of change and reform.

The pre-legislative process is an example of where civil society intervention (of whatever hue) can enrich the process of decision making without stepping on executive or legislative prerogative. If "civil society" denotes "citizens" unattached to a party or government, then the very notion of democracy mandates active participation of the citizenry in all forms of governance. Therefore pre- legislative consultation is an important area for civil society to enlarge spaces for citizens' participation in the framing of law and policy.

There is concern that civil society groups leading the current agitation against corruption have a political agenda and are seeking to foist solutions upon the country. Would you agree with this?

Every group is likely to push the solutions it believes in. However if the group becomes part of the formal State apparatus (like the Lokpal Joint Drafting Committee), then it becomes its responsibility to throw open the debate and make it inclusive and transparent. Fighting corruption is part of politics, both in the narrow and the wider sense. Therefore political affiliations with a particular ideology are relevant to contextualize their efforts. In terms of a discussion on specific legislative/systemic changes, there is a need for a robust and vibrant debate that can look beyond party politics and allow open discussion, free of the need to follow the party whip.

Fighting corruption is in the larger public interest. Do you think politicization of the issue and the strategy being used currently is actually taking us away from a durable solution?

Corruption is a far more complex issue than is being understood in the current debates. There is a basic politics of power that enables and drives corruption. This needs to be addressed and overcome. Therefore real change will only come about when those relationships of power and issues of injustice are also part of the solution.

On the other hand, corruption is also a convenient political issue to be superficially raised by all mainstream political parties - in particular when they are in opposition. When parties equally steeped in corrupt and unethical practices seek to support and gain mileage from popular movements, the movements are likely to find themselves in the midst of partisan innuendoes, with the search for systemic solutions fading away.

In addition to demanding systemic reform, anti-corruption movements need to identify and demand action on those instances of corruption that exemplify their specific area of concern. This makes it clear that fighting corruption is not merely seeking a legal remedy, but in fact part of a long and sustained campaign where the law is only one part of the solution. Eventually, solutions lie in the socio-political framework.

You are personally being accused of being pro-government. What is your response?

As an RTI activist and a member of the MKSS, I do believe that the government has been created to work towards guaranteeing people access to their needs and rights, enshrined in legislation, the Constitution, and in democracy. Government, as commonly understood and used for a variety of institutions and structures, has to be accountable. I am neither pro nor against government per se. It is an institution which must deliver.

As a member of a workers' organization and as believers in democracy, we believe that the government carries with it the onus to protect and deliver constitutional and other legislated rights to the people. It is a powerful protagonist in the lives of common people, regardless of the name or ideology of the political party in power. It is the face of a huge organization created through the vote, where, along with civil servants, a structure has been created to implement promises made to the people. But government has acquired more power than the people who are theoretically the sovereigns of a democratic structure. Those of us who work with the poor and marginalised, demand transparency and accountability in engaging with the government so that it follows its basic mandate to serve all people, regardless of their political leaning.

The government in India has often been hijacked by classes of people who have selfish and subverted designs on the system to make it deliver to suit their interests. What in old fashioned vocabulary was called 'The Establishment.'

I have never hesitated in speaking out against decisions or policies that I disagree with. I have opposed positions even while I have been in the NAC , in recent times, policies such as the UID project, the government's stand on non payment of minimum wages to MGNREGA workers, the BPL cap etc, POSCO and many others. Most importantly, I joined the NAC to further the cause of the people I work with - most of whom are poor and marginalised. The stands I have taken have come from my personal convictions and what I perceive to be the impact of a particular policy on the ordinary citizen. That is the tilt I believe in.

One view is that what we are seeing on the streets today is the result of having an NAC which is being described as having no legitimacy and being extra constitutional. What do you have to say?

The NAC is only a part of the support structure like many other councils and committees set up for specific purposes, that renders advise to the government on social policy. Members are not from one campaign, ideology, sector or grouping. The members represent varied interests of different marginalized groups, and hence the NAC has to deal with debate and disagreements within its forum. The Chairperson is a part of all the deliberations of the full NAC and in matters where there is a difference of opinion the final decision is taken by the full NAC and the Chairperson.

The NAC is a formal advisory body constituted by the Prime Minister, with the chairperson of the ruling body as its Chairperson. It is purely advisory in nature - where all policy and legislative recommendations merely feed into the deliberative process of the Executive, including the Cabinet, where they are extensively debated and changed. From the Cabinet the draft law goes through the regular Parliamentary process. It is worth noting that no draft of the NAC has been passed by the Cabinet unchanged. Therefore, it cannot be seen as an extra constitutional body, in theory or practice.

The NAC in fact serves as a platform for citizen's engagement with the government, and to that extent furthers democratic processes. It needs to be seen as a new and evolving institution for formal engagement with people who represent varied interests of the poor, but who may not be in a position to find space to impact government. It is one kind of process of legislative consultation, but the concept and fora have to evolve, and more such platforms need to be created. The immediate need is to clearly define NAC processes, and thus make its functioning transparent - the NAC could then serve and evolve as an important platform for participatory democracy.

What is the consultative process followed within the NAC?

The NAC has a mandate to serve as the interface between the government and the people potentially affected through its laws/policies. It focuses particularly on social sector laws and their effect on marginalized and disadvantaged communities. The NAC is mandated to hold public consultation of laws before they are forwarded to the government as draft bills. In other words, it attempts to ensure people's participation in the process of drafting law and policy. As part of its procedures, the NAC prepares draft Bills (or framework/basic principles). The NAC procedures lay down a process of consultation to be followed by working groups set up to work intensively on issues. The working groups, draw upon opinion from experts and affected people. The report prepared on the basis of consultations by the working groups are presented for discussion in the full NAC.

After extensive consultations between members, and with considerable engagement with government ministries, these drafts are made public, for comment. The NAC attempts to incorporate the feedback, received till the process of consultation is complete. The NAC then forwards its view to the government as a series of recommendations.