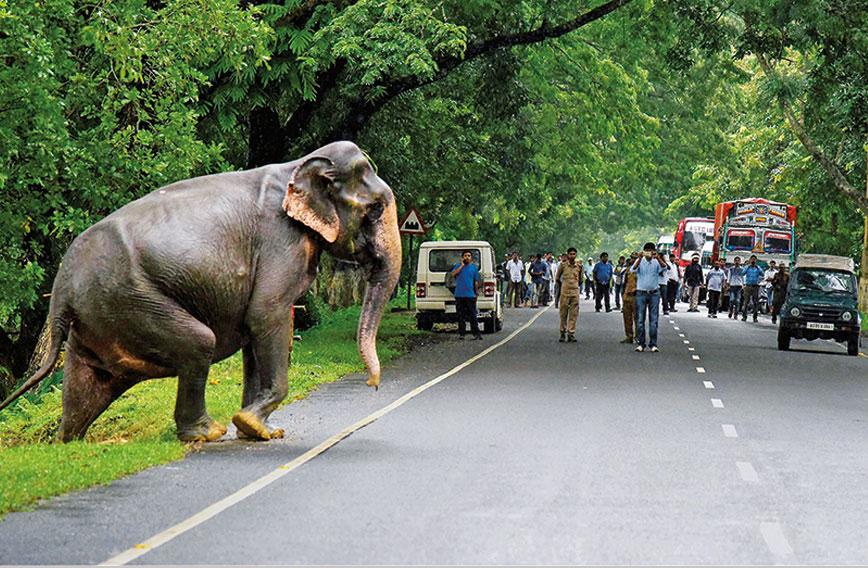

Roads that go through wildlife areas should be closed at night to give animals relief

Cruel road ahead for animals on the edge

Slumped on the road, the leopard attempted to rise, but fell. She hauled herself up only to crumple again. Somehow, she stumbled and crawled, every movement agony till she reached the forest across and collapsed under the shade of a tree.

Slumped on the road, the leopard attempted to rise, but fell. She hauled herself up only to crumple again. Somehow, she stumbled and crawled, every movement agony till she reached the forest across and collapsed under the shade of a tree.

Ordinarily leopards, the smallest of the big cats, are masters of stealth, making up for size with their versatility and agility. But this wild cat was broken. She was the victim of a hit-and-run case on May 14 on the recently widened Mul-Chandrapur road that skirts Maharashtra‘s Tadoba Tiger Reserve. The leopard lives — wounded, disabled and caged in a ‘rescue’ centre, until death releases her.

She is one amongst the many animals maimed and killed on this road — deer, tigers, a sloth bear, snakes, skinks, boars, birds, butterflies, frogs…innumerable in death, creatures that don’t count.

The Mul-Chandrapur road is not the only hotspot for such high mortality. Vehicles are voracious predators. Highways, railways, canals and other such linear projects crisscrossing wildlife reserves and habitats as well as speeding vehicles running over wild animals are one of the main drivers of extinction, globally.

Roadkills, a crowdsourced ‘Citizen Science’ initiative launched by the Mumbai-based Wildlife Conservation Trust (WCT) to document wild animal mortality in India, estimated that 20 elephants, 25 leopards and one tiger were killed due to linear infrastructure in just 100 days earlier this year.

This is a conservative tally. It mainly enumerated large, charismatic animals. The regions covered were opportunistic, rather than exhaustive. Milind Pariwakam, a biologist with WCT, says the number of animals killed on roads across India annually “would likely be in millions”. This isn’t an exaggeration but probably an underestimation.

Railway lines are equally destructive. More than 1,200 trains crisscross India’s Protected Areas (PAs) — national parks and sanctuaries. According to Gajah, a report by the Elephant Task Force appointed by the Union environment ministry, out of 88 identified elephant corridors, 61 have highways and railway tracks cutting across them.

The death toll is enormous. In April this year, four elephants were hit by a train in Odisha’s Ganjam district. In December, five died while crossing a railway track in Assam. One of the worst accidents was in North Bengal in September 2010, when seven elephants were mowed down by a speeding train as the herd tried to save a calf that got stuck on the Sevoke-Rangpo ‘killer track’. Over 2004-15, no less than 50 elephants met their death here. Yet the line is currently being expanded, meaning more trains, greater speeds and more fatal accidents.

The massacre is not always so blatant. Death comes by stealth. A telling example is of the Mughal Road which was upgraded and widened from a kutcha path to make a supplementary connect between Srinagar and Jammu. It cuts through the Hirpora Wildlife Sanctuary, home to one of the last viable populations of the Pir Pinjal markhor, a rare wild goat emblematic of these mountains.

Road construction began in 2007. The blasting, consequent soil erosion and dumping of debris destroyed critical markhor habitat. The markhor is a hardy animal, surviving harsh winters and negotiating sheer cliffs as well as tough terrain. Yet, it is unlikely that the markhor will survive the advent of the Mughal Road. In the past decade, markhor numbers in Hirpora have halved to about 30, and experts fear that the species may become extinct here.

There are other less obvious but equally lethal effects of linear intrusions. One implication is greater access. In the Hirpora sanctuary, the Mughal Road gave easy access to graziers who brought in sheep in truckloads. The sheep flocked the meadows, leaving no feeding grounds for the markhor, who risk starving to death.

Power transmission lines can be equally fatal, as in the case of the Great Indian Bustard (GIB) of which fewer than 150 survive in the wild. The GIB’s last remaining habitats in the desert of Rajasthan and Kutch are where renewable energy projects are concentrated. Wind and solar projects, while critical as a clean source of energy, are land-intensive and can have fatal impacts on biodiversity. Five GIBs have been electrocuted by transmission lines since June 2017. When such a small population continues to lose its habitat to development, the loss of each bird is catastrophic.

Linear intrusions splinter landscapes, making tiny, dysfunctional fragments of a thriving ecosystem. Think of an heirloom Persian carpet which is priceless in itself but worthless if shredded into pieces.

They cut off time-worn migratory paths of wild species, enclosing them in small forest patches. The spill-over effects are visible on either side —thinning, dying trees, decaying vegetation, intrusion of invasive species and retreat of wildlife. Biologists call this the ‘Edge Effect’. Species in such broken forests decline, and are more likely to become locally extinct.

Consider the Central and East Indian Tiger Landscapes, one of the finest, largest habitats of the big cat in the world. If wild tigers are to survive in the long term, this is one of the few places they will flourish, if we don’t slice and snip through them. This landscape spreads over eight states and harbours about a third of the country’s 2,226 tigers in a network of PAs connected by increasingly fragile wildlife corridors.

The Wildlife Institute of India estimates that in an inviolate space of 800 to 1,000 sq km a population of about 80 to 100 tigers is essential to ensure their safe future. A smaller space is not genetically viable on its own. By this yardstick, not even one sanctuary or park in this entire landscape can sustain itself. Hence connectivity between these small PAs is important to allow tigers to travel and retain genetic vigour.

Let’s zoom in further to the region which inspired Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book — the tiger reserves of Kanha and Pench which straddle both Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Pench’s 411 sq km is inadequate for a viable tiger population. But it is connected to the more sizeable Kanha Tiger Reserve through a living corridor. The 200-odd tigers of this 16,000-sq-km landscape thrive because of landscape contiguity, which is now threatened by the expansion of National Highway (NH)-7 and the Gondia-Jabalpur railway line. Increasing fragmentation will irrevocably break up this vast landscape, confining tigers into isolated reserves, eventually leading to their extinction — poaching kills instantly, while in the long term, genetic decay over generations will annihilate the tigers.

Another example is the Mul-Chandrapur road that felled the leopard. It runs along the southern periphery of Tadoba, severing animal movement to Telangana’s Kawal Tiger Reserve. Kawal is a young reserve, notified in 2012, and has been battered over the years by deforestation and hunting. Its tiger population is very low and needs to be secured, protected and nurtured. Vital to its survival is connectivity with Tadoba which has a ‘source’ breeding tiger population that can populate Kawal. Widening of the road, plus the recently approved Ambedkar Pranahitha canal project, further disturbs this corridor. For Kawal, such isolation is suicidal.

Roads and other projects are being pushed through eco-fragile areas, including national parks. The cruellest of cuts is the proposed National Highway that goes through the heart of the Corbett Tiger Reserve, which has 15 to 17 tigers per 100 sq km — amongst the highest densities of tiger in the world. Corbett is one of India’s oldest tiger reserves. This is where Project Tiger, a pledge of the government to commit to protect its national animal, was launched in April 1973. If you can knowingly violate Corbett, what hope is there for other PAs?

Another controversial plan is the ongoing road widening of the 900-km Char Dham route in Uttarakhand. The road will cause untold pressure on the delicate Himalayan ecology. The blasting and denuding of mountains will increase the threat of landslides manifold and accelerate the devastation caused by natural disasters. The losses can be colossal, as witnessed during the floods and landslides in Uttarakhand in 2013.

The environment ministry’s guidelines state that expansion of an existing highway less than 100 km does not require a green clearance. So, the ministry of road transport and highways has chopped the Char Dham road into segments of 53 stretches — all less than 100 km — to avoid the rigours of environment scrutiny. This means that the cumulative impact of cutting trees, blasting slopes, deforestation and disposal of debris has not been considered.

The road ahead looks grim. Yet the carnage can be minimised and animals allowed their right of passage.

One way is mitigation. Culverts, underpasses and overpasses can be built and maintained. Mitigation must be done keeping in mind the behaviour and ecology of the species concerned. For arboreal animals, artificial canopy ‘bridges’ at vital points allow for safe passage. So will maintenance of a natural canopy and green cover along the edges of roads. It is vital to build in ecological considerations at the planning stage with meetings and dialogue between all relevant stakeholders.

One simple engineering quick-fix is to create speed regulations in wildlife-rich areas and to deploy speed breakers.

Certain roads which go through important wildlife areas can be closed at night, giving the animals relief and room for movement. This is currently in place on the highway that passes through Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka and links the state to Kerala, though in a recent move the Union ministry of road and transport is putting pressure on Karnataka to open the road to night traffic and also proposes to widen it.

We need to question the social and ecological costs of roads. A Global Strategy for Road Building by W.F. Lawrance et al pinpoints areas with high ecological value that must remain roadless, and those where benefits to human beings in terms of agricultural development, employment and so on come with relatively little environmental harm.

A similar strategy for India with comprehensive mapping of wildlife habitats and corridors should form the basis on which road infrastructure is planned. PAs, pristine habitats, river catchment areas, wetlands, and crucial wildlife corridors should be left alone. Where roads must be built, the extent, width and type of road should be carefully planned. Scientific, ecological inputs must be inbuilt into mitigation plans.

As a member of the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), we were overwhelmed by the number

of proposals for road projects within and around PAs and prepared comprehensive guidelines in

2013. The thumb rule for PAs and pristine habitats was to avoid new roads and seek alternative

routes. No upgradation and expansion was advised for existing roads in sanctuaries and national parks. The environment ministry accepted these recommendations, but failed to put them into practice.

For instance, an alternative route to the contentious NH-7 was recommended. It added another 80 km and about 90 minutes of travel time but it would save a forest, and its tigers. Similarly, when faced with the decision to allow construction of a road that would go through Kutch Wildlife Sanctuary and endanger the only nesting site of flamingos in the Indian sub-continent, an alternative route was suggested by the NBWL’s Standing Committee. But the suggestion wasn’t taken on board.

We do make and take bypasses through cities. Would we consider building a road through the Taj Mahal, which if, God forbid, is defiled could conceivably be built again. But a species lost, a forest destroyed, vanishes forever. Why then do we still consider forests expendable?

Comments

-

Asphalt Mixing Plants - April 1, 2019, 11:46 a.m.

Your personal post is very good. Private insight. I like it completely. I am browsing for a answer in connection with roads construction for my clients. I will share your personal article with our consumers. With regard to his reference. all the best