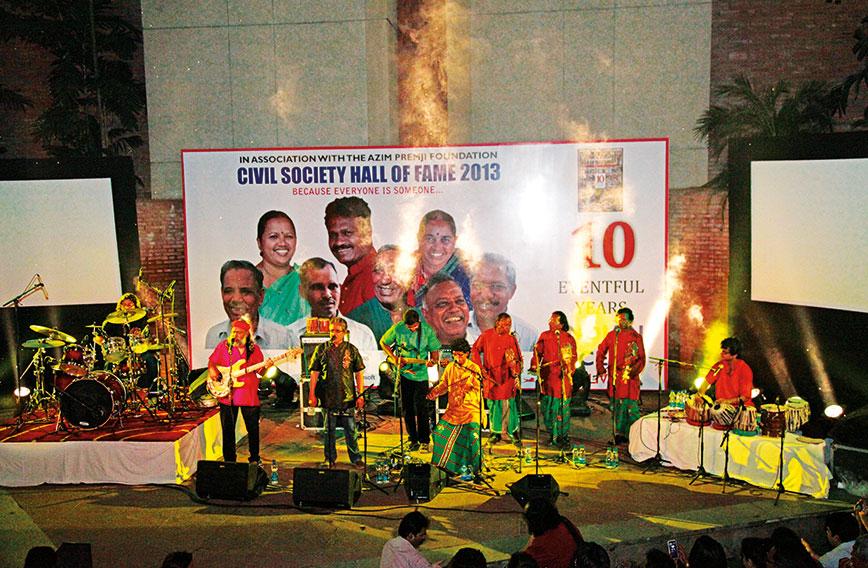

Indian Ocean performing with tribal musicians at Civil Society’s Everyone is Someone Concert

Lyrics, scales and a modern sense of Indian-ness

How did your band come up with the name Indian Ocean? This is a question we have been asked countless times. To many people the name perfectly captures the feel of the music of our band. In the words of a friend, “Fiercely Indian, effortlessly global.”

How did your band come up with the name Indian Ocean? This is a question we have been asked countless times. To many people the name perfectly captures the feel of the music of our band. In the words of a friend, “Fiercely Indian, effortlessly global.”

The truth is that the name was suggested by A.K. Sen, the father of Susmit Sen. Susmit was a co-founder and guitarist of Indian Ocean from its conception in 1990 till 2013. Apparently, according to Asheem Chakravorty (our other co-founder), there was a naamkaran (naming) meeting over lunch at Susmit’s house and lots of names were being thrown around, when Susmit’s father suggested, a bit hesitantly, “How about Indian Ocean?” The name was accepted instantly!

So there was no great plan, and the name came about serendipitously. In a sense, this applies to the entire career of the band. We never really had a plan. We were and are pretty bad at the business part of running a band, and our PR is fairly non-existent.

So how did Indian Ocean come to be known as a band that seems to exemplify modern India? I think we represent that part of civil society in India that is very comfortable with its Indian-ness, without feeling the need to beat others over the head with it, or to shy away from the not-so-pretty side of our culture. We openly acknowledge the absorption of all manner of musical influences without getting hung up on roots and purity, as exemplified by our use of Western instruments.

Another small part of the answer lies, of course, in our sheer longevity! The band has entered the 29th year of its existence, and has performed over 1,100 shows across the globe. Thus, a vast number of Indians have heard us. Young people who heard us in the 1990s are now fairly senior in their professions. They bring their kids to our shows, and relive their college days! Our audiences range from people my parents’ age to toddlers — many of whom force their parents to play Indian Ocean songs ad infinitum. I have had parents urge me: “Please bring out new material, we keep hearing the same songs over and over.”

The main answer to why Indian Ocean is the best musical representative of civil society in India lies, of course, in the content of our music. Our music uses Indian scales, and very Indian-sounding melodies, for the large part, and our rhythm patterns are strongly Indian in sound and feel. Our lyrics are in a range of Indian languages (10 at last count), but mainly in Hindi.

But then, one can say this about a lot of Hindi film music as well. What does stand out, in my mind, is that, in addition to the relative complexity of our music, our lyrics speak to a range of emotions and issues in ways that most lyrics do not. I shall try to loosely transliterate a few lines from a couple of our songs to illustrate.

Dhoom machi, har nabh mein phootey ras ki phuharein

Anhad ke aangan mein naachey, chanda sitarey

Noise everywhere, the skies are full of emotions.

The moon and stars dance in the courtyard of the infinite (Khajuraho, 1999).

These lyrics were written by Sanjeev Sharma for a song we performed at the temples of Khajuraho, a celebration of 1,000 years of existence of the main temple there.

Then there is our biggest hit, Bandeh, from the movie Black Friday, a song written by Piyush Mishra in 2004. The movie told the story of the serial bomb blasts that ripped through Bombay in 1993.

Arre ruk ja re bandeh, arre tham ja re bandeh, ki kudrat hans padegi ho

Arre neendein hain zakhmi, arre sapney hain bhookhe, ki karvat phat padegi ho

Stop, my man, desist, and nature will laugh. Wounded sleep, starving dreams, torn apart, tossing restlessly.

From spiritual contemplation of the infinite to horror at the carnage human beings can wreak…that’s quite a range! There is a lot of spirituality in Indian Ocean’s lyrics but very little overt religiosity. In fact, a couple of us are atheists.

While we have had quite a number of songs written for us specifically, we perform many versions of pre-existing songs and poetry. We sing two hymns: Ma Rewa (a song from the Nimad region of MP in praise of the Narmada) and Kandisa (a Syrian Christian hymn in Aramaic, believed to be over 1,900 years old); there are songs with Sanskrit shlokas from the Vedas and the Upanishads (Khajuraho, From the Ruins, After the War); a couple of poems written by Sant Kabirdas; a folk song from Karnataka (Tandanu); modern poetry written by activist-poets (Hille Le by Gorakh Pande, Gar Ho Sakey and Chitu by Shankarbhai Tadavala, Boll Weevil by Vahru Sonavane, Zindagi se Darte Ho by N.M. Rashid)…the spread of songs is wide, the content varied, and the fun singing them is, of course, beyond measure.

Of the songs written specifically for us, almost all are in Hindi, written mainly by Sanjeev Sharma, whose lyrics have a strong spiritual and Sufi-ish bent. Piyush Mishra wrote the three songs for Black Friday and Varun Grover has written the songs for Masaan. We tend to try and evade the verse-chorus format, and our lyrics are, by and large, sparse.

But this is still not the entire story. Indian Ocean, somehow, manages to do things with their songs that take history, culture and politics and make rocking songs out of these. We peer into forgotten nooks of our culture, and we tend to explore issues that nobody sings about.

My favourite story involves the song, Chitu. My good friend, Amita Baviskar, was doing research on the Narmada Bachao Andolan, and went to the national archives to look up the recorded history of the region. She found histories of the Bhils who had fought the British, and told these stories to Shankar Tadavala, who is a poet-activist with an organisation called the Khedut Mazdoor Chetna Sangath, which operates chiefly in the Adivasi-dominated Alirajpur tehsil of Jhabua district in Madhya Pradesh. Shankarbhai composed an extremely catchy song using these stories, and I learnt it from him one day in February 1993.

Chitu Bhil was a local chieftain who fought the British in 1857-59. When the British finally killed Chitu, they converted his small bungalow into a police station. Just two days after learning this song, I, along with another activist called Ashwini Chhatre, now a professor in an American university, was arrested and sent to Chitu’s bungalow, to the police lock-up.

Amazed at this coincidence, we sang Chitu loudly in the lock-up. The thanedar was so impressed with our singing that he brought us wonderful warm food — bajra rotis with ghee, dal and jaggery — from his house!

More than 20 years later, we recorded Chitu. We had the amazing kanjira player, Selvaganesh, play this song with us, since we felt he would love the 10-beat cycle of the song. This is, I feel, the essence of what makes Indian Ocean stand out in contemporary Indian music. We have had audiences sing along to the chant that is an essential part of this song.

Another story involves the song, Roday. I had heard a song in Bhili sung by this extremely pretty Adivasi woman named Jimli, in the Gujarat part of the submergence area of the Sardar Sarovar Dam. This, too, happened in February 1993. For years, we tried to complete this song, but we were getting nowhere past the first three minutes.

One day, in January 2014 at our practice place in Ghitorni, a discussion between Amit Kilam and me led to the thought that we should look upon this song as relating to displacement, since Jimli’s village now lies submerged under the waters of the dam, and her villagers are scattered. I felt that Amit, a Kashmiri Pandit, too is a displaced person, as his family fled the Kashmir Valley in the early 1980s, when Pandits were being threatened to leave while the government stood aside and watched this ethnic cleansing.

Soon enough, Amit’s mother wrote some lines in Kashmiri, about a tree that had to be moved…it lived, but without all that had sustained it earlier. Then we approached Vishal Dadlani (Indian rock star and film musician) with this song, who said that he, too, came from a displaced community since he was a Sindhi, and they were forced to leave during Partition. Vishal came up with these extremely powerful lines and tune in Sindhi.

Thus was Roday born…a song in Bhili, Kashmiri and Sindhi, which is about displacement in modern India! I’m sure there is absolutely nobody in our audience who understands the complete lyrics of the song, but it is a powerful song, and totally rocking when played live!

So this is us. We sing songs of spirituality and philosophy, songs of history, songs that show our love for our fascinating complex culture. We also have instrumentals that leave the audience in raptures. In addition, individuals in the band have varied political, philosophical and religious attitudes. One of our members was very opposed to the idea that our music is political. We have people who vote for very different parties.

But here is what we have in common, a sort of common minimum programme, if you will: We never play for any political party; we are completely non-communal; we shall never make a song that is discriminatory about religion, gender, caste or colour; we work rather democratically, in that everybody contributes to the music; a song is never complete, it can constantly be reworked; our songs tend to be way longer than most contemporary popular music; we pay as much attention to the instrumentation and arrangement as we do to lyrics, so that no two songs sound the same, yet we have an instantly recognisable sound; we tend to sing in pitches that are a bit on the high side!

In short, we are proud of our culture, but not blind to its shortcomings.

We are also, by and large, surprisingly free of angst regarding our parents. Susmit’s father gave us our name. All our parents encouraged us in our chosen careers. Amit’s mother has written partial Kashmiri lyrics for two of our songs — another reflection of the Indian ethos, where generations live together relatively amicably.

In recent years, after Asheem died in 2009 and Susmit left the band in 2013, I feel the sound has tended to become more rock-like, with a touch of Carnatic (thanks largely to our guitar player, Nikhil Rao), our tabla parts have become more complex (thanks to Tuheen Chakravorty) and our vocals have a touch of the classical (thanks to Himanshu Joshi). Amit Kilam (drums, recorder, gabgubi, clarinet and vocals) and me (bass guitar and vocals) have now become the grand old men of the band (as has Dhruv Jagasia, our manager who has known us now for over 20 years), and we continue to love what we do, as apparently do our audiences.

Rahul Ram is a founder-member of Indian Ocean

Comments

-

Indrajit Dasgupta - Dec. 10, 2018, 8:28 p.m.

Rahul, I was already a great admirer of Indian Ocean. I now have become a 'bhakt'. Seriously, Ram, a great article.