Avalanche to disaster: What really happened

Civil Society News, New Delhi

On February 7, the Rishiganga in Uttarakhand suddenly turned virulent. Laden with boulders, water and ice it crashed through its banks in Chamoli district causing an unexpected flash flood which reverberated all the way downstream.

Bridges and dams were destroyed and lives lost. The scene of death and destruction that unfolded evoked memories of the terrible Kedarnath flood of 2013. Clearly no lessons had been learnt from that tragedy. Dams, tunnels and road construction in this ecologically sensitive region had continued, leaving no scope to absorb a natural occurrence.

After the Kedarnath flood, Ravi Chopra, director of Peoples’ Science Institute (PSI) in Dehradun, was appointed to an expert committee tasked with assessing the environment damage caused by dams in this region.

Civil Society spoke to Chopra, now retired from PSI, about why this flash flood happened and what had been done since 2013 to reduce the risk of damage from natural occurrences.

It is being said that the current disaster is due to glacial melt. Nothing to do with dams. What is your assessment?

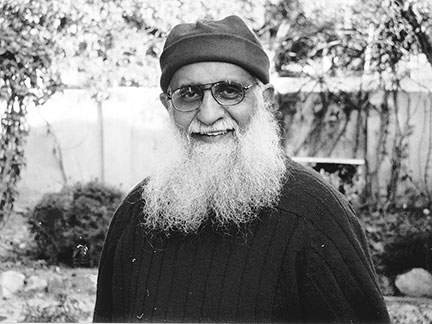

|

Ravi Chopra |

A number of terms have to be carefully understood. Two separate events occurred on February 7. The first was an avalanche that came down a small mountain stream valley, a tributary of the river, Rishiganga. When this colossal mass of snow, water, ice, sediments, debris, rocks, boulders hit the Rishiganga it created a flood in the river. This was a natural event. Such events are not infrequent in the region.

The second event was the disaster. When such a colossal flood meets a barrier, it smashes the obstruction and moves further downstream with greater energy. In the process it picks up more sediments — rocks and boulders lying on the river bed — and more energy, until the riverbed slope decreases.

The first barrier, a bridge across the Rishiganga, was easily destroyed. The second was the small 13.2 MW Rishiganga hydroelectric project. That was removed. Then the flood entered the valley of the larger Dhauliganga (West) river. The first barrier on this river was the barrage of the large 520 MW Tapovan-Vishnugad dam. That was swept aside and here the water also entered the intake tunnel. The mouth of the tunnel was blocked by the boulders and other flood-borne sediments. This trapped the labourers working inside the tunnel. The flood then continued downstream, destroying a suspension bridge near Joshimath and petered out a little later.

Putting obstructions in the path of the flood was the cause of the disaster and this was manmade. Had there been no barrier in the path of the flood, it would have entered the larger Alaknanda Valley and gradually petered out as the bed slope decreased. The damage would have been minimal.

Do we know enough about glacial lakes in the upper reaches of the Himalayas? Have these been mapped?

No, we do not know enough about glacial lakes in the upper reaches of the Himalaya, though a glacial lake inventory of Uttarakhand was created using Landsat images and it was published in 2005. I am not aware about how thorough the inventory is.

It is important to understand, however, that the evolution of glacial lakes is a dynamic process. Due to global warming glaciers not only recede but they also shrink and fragment. Smaller glaciers tend to fragment or break up more easily and form glacial lakes. The lakes which develop in the front and at the margins of a glacier are prone to GLOFs (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods). The latter can create havoc in populated valleys like the Kedarnath flood in 2013, though that flood was not the result of a GLOF.

Satellite imagery of the Himalayan ranges is available. Uncoordinated efforts are underway in different institutions to study these images. There was talk about establishing institutions for glacial research. Two institutional proposals were made in 2008 and after 2013. But both the ideas have been dropped recently.

After the flood disaster of 2013, what has the government done by way of policy to protect this ecologically sensitive zone in the Himalaya?

Immediately after the June 2013 flood disaster a lot of contrite statements of good intents were made by decision-makers -- ministers and bureaucrats. Unfortunately, there was little follow up on the ground, except that some research studies were commissioned. Soon after, however, with the short political horizons of the party in power, all focus on developing sustainably was abandoned in favour of a strong push for rapid economic growth. Caution was thrown to the winds.

Court orders to build away from river banks were ignored. A hasty and ill-conceived programme to widen almost 900 km of the Char Dham highways was begun. There have been constant demands to relax regulations in the Bhagirathi Eco-sensitive Zone (BESZ). Eco-sensitive zones around designated wildlife sanctuaries are constantly violated in planning and building roads. There are calls by senior political leaders to shrink or de-notify protected areas. Similarly, there is constant lobbying by state officials and ministers for restarting hydropower projects stayed by the courts or by the central government.

What action did the government take on the report of the Committee you headed to assess how far such projects caused the flood disaster of 2013?

Two members of the Committee from the Central Water Commission and the Central Electricity Authority, both strong pro-dam agencies, submitted a separate report as a protest against the report submitted by the rest of the committee. The Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) did not accept their report.

In December 2014, the MoEF filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court stating that it had accepted the report and all the recommendations in it. Soon after, organizations/agencies whose six dams had received prior approvals challenged the report’s recommendation that their projects be cancelled. Thereafter, a Supreme Court appointed committee endorsed the decision to scrap the six dams. MoEF then appointed a third committee in which, to my knowledge, no environmentalists and social sciences experts were included, to get a report in favour of building hydro power projects. The original case continues in the Supreme Court.

The residents of Srinagar town blamed the sudden release of water by the Srinagar HEP and the massive amounts of sediments piled downstream of the dam for the destruction of their homes and businesses. Based on scientific data in the report, they went to the National Green Tribunal (NGT) demanding compensation from the hydropower company. The NGT awarded over Rs 9 crore to the victims. The case was appealed by the company and a final decision is still awaited.

What is the status of the 100 km stretch from Gaumukh till Uttarkashi which was declared as eco-sensitive zone?

The Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone (BESZ) from Uttarkashi to Gaumukh, notified in December 2012 under the guidance of Jairam Ramesh then Union Minister for Environment & Forests, still survives with its sensitive slopes and beauties intact. But ever since its notification, politicians and the contractor lobby has been pushing for its denotification. The original notification was amended in April 2018 under great pressure from the Uttarakhand government to relax the regulations. Fortunately, however, due to strong opposition from environmentalists and some sensitive officials at the Centre, 10 hydropower projects in the stretch have finally been cancelled and the Uttarakhand government has accepted that decision.

The Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRTH) is lobbying very hard to relax the BESZ regulations in order to widen the highway under the Char Dham Pariyojana.

I am strongly opposed to any relaxation in the original regulations, except the minimum required for defence purposes and transport safety.

A lot of destructive activity takes place because of tourism. Is there any regulation or any policy at all on tourism?

A good decision was taken a few years ago by the Uttarakhand government to limit the damage due to uncaring tourism. Only 150 persons and 20 ponies are allowed to travel from Gangotri to Gaumukh every day. This followed the heavy damage and litter caused by hundreds of daily visitors going to Gaumukh after the Kanwar festival every year. The state government has prepared a policy to promote home stays and spread the benefits of tourism in Uttarakhand.

Otherwise, major programmes like the Char Dham Pariyojana to enable lakhs of tourists to visit the four shrines in the inner Himalaya, the preparation of a master plan for urbanizing Badrinath, the modernization of Kedarnath, the construction of large hotels in sensitive locations are all indicative of a massive push for expanding tourism at the cost of the environment.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!