Lakshadweep troubled, can it be like the Maldives?

Susheela Nair, Bengaluru

WITH its shimmering lagoons, coral reefs, a line of silver sand beaches and rows of coconut palms, the serene Lakshadweep archipelago is a paradise for tourists and environmentalists. But in recent weeks Lakshadweep has been making it to the front pages not for its natural beauty, but regulations that the administrator of the islands proposes to impose on them.

Praful Koda Patel, administrator since 2020, has rapidly drafted regulations which local people object to because they tamper with their way of life. The majority of the population, about 97 percent, is Muslim, but the administrator has proposed allowing bars to open and a ban on beef. The people on the islands depend upon dairying and breeding of bovines for a livelihood.

He has proposed limiting local self-governance, which the islanders cherish, and centralizing key decisions in education, health, fisheries, animal husbandry and so on. This authority is being passed on to respective directorates under the administrator, undermining local self-governance.

In addition, it is proposed to allow detention for up to a year without citing reasons under the draft Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation Bill (PASA), 2021. But Lakshadweep has one of the lowest crime rates in the country, according to the 2019 report of the National Crime Records Bureau.

What has angered islanders the most is the draft Lakshadweep Development Authority Regulations (LDAR) 2021, by which the administration can acquire residents’ land for development without safeguarding their rights. There are plans to build roads 15 metres wide, but locals say Lakshadweep does not need highways and that such projects will damage the islands’ fragile ecology. The size of the largest island, Androth, is just 4.9 sq km.

Though the Integrated Island Management Plans (IIMPs) stipulate that all development envisaged in the IIMPs shall be implemented in consultation with the elected local self-government bodies, LDAR regulations completely ignore the recommendations in the IIMPs.

The idea seems to be to turn Lakshadweep into a tourist paradise akin to the Maldives. Environmentalists and scientists studying the islands say they can’t be transformed into a tourism hub because of their ecology and the increasing pace of climate change in the Arabian Sea.

A fragile ecosystem

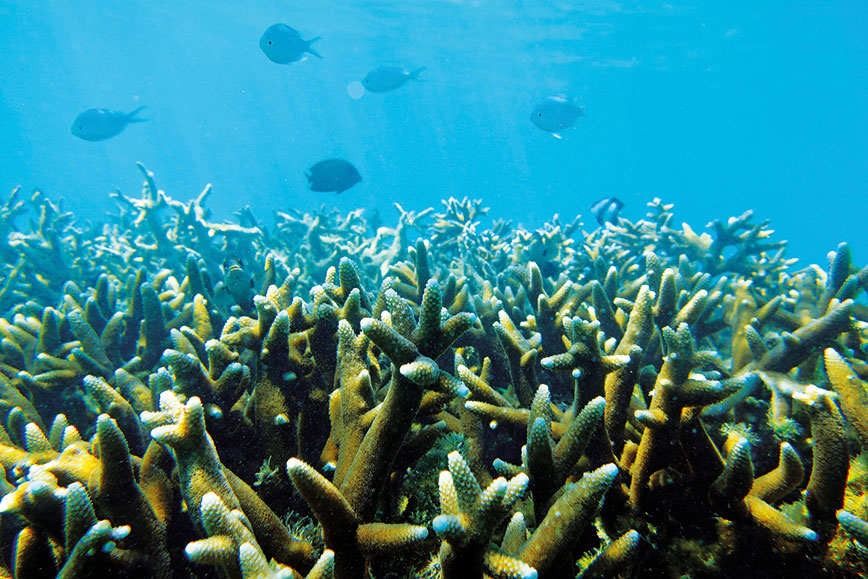

“We have been working in Lakshadweep, one of the most climate vulnerable locations in the world, for the past two decades, unpacking the ecological consequences of climate change on the islands’ reefs,” says Somesh S. Menon, project associate, Oceans and Coasts Programme, Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF).

“Our studies reveal that rising sea surface temperatures and frequent El Niño-related coral mortalities have resulted in dramatic losses to the reef. With the death of coral, fish and other creatures that depend on them also decline. Our research has shown that with each subsequent coral mortality, the ability of the reef to recover reduces drastically.”

Activists go underwater to protest

Activists go underwater to protest

“The habitability of low-lying oceanic atolls like Lakshadweep is heavily dependent on the health and growth of its coral reefs. When healthy, the outer reefs form a self-repairing fortress of living coral around the atoll, which ordinarily keeps the highly sensitive terrestrial and marine systems safe from major ecological turbulences. The decline of the reefs represents a loss of biodiversity and ecosystem function, but more critically, undermines the very habitability of atoll islands. By many accounts, these atoll systems are expected to become uninhabitable within a generation because of catastrophic coral mortalities and rising sea levels,” says Menon ruefully.

According to Menon, at present rates it will take more than three decades without another major disturbance for complete recovery in Lakshadweep. This is unlikely because the pace of climate anomalies is increasing in the Arabian Sea.

Even more worrying, the loss of coral signals a loss of physical integrity of the atoll structure that protects islands from storms, reduces coastal erosion and ensures precious freshwater resources are preserved.

This precarious ecological balance is being further strained by an export-oriented reef fisheries industry. Once a marginal fishery, it has been steadily growing in the islands over the past decade, resulting in the removal of key fish species, crucial for reef recovery after mass disturbances. As reef fishing becomes increasingly commercialized, it will not be long before the natural limits of survival in Lakshadweep are breached beyond repair.

Erosion is indeed a problem on many of Lakshadweep’s beaches. Earlier, Lakshadweep had 36 islands but due to coastal erosion, at present there are only 11 inhabited islands and 15 uninhabited ones. The island of Parali I, part of Bangaram atoll, one of the biodiversity-rich islands of Lakshadweep, has vanished due to soil erosion and other similar territories are fast shrinking.

There is also an assortment of open and submerged reefs, sandbanks, and so on. “While wave action on beaches is a common geological process, extensive beach erosion and accretion (the creation of new sandy areas) from ‘unscientific, indiscriminate dumping’ of concrete tetrapods (structures used as a seawall to reduce wave action) has already impacted the islands’ beaches, says the 2015 IIMP that governs management activities on 10 islands of Lakshadweep,” points out Menon.

Despite occupying an area of less than 32 square km the islands are home to more than 70,000 people, making them one of India’s most densely populated regions. “The fragile ecosystem with limited freshwater resources and absence of surface water bodies such as streams, lakes and rivers has added to the woes of the islanders. Despite receiving high rainfall, the low availability of subterranean storage coupled with the high porosity of the aquifers which allows for the infiltration of seawater into groundwater, makes freshwater a precious commodity for the islands,” adds Menon.

Taking into consideration the recommendations of the Justice Raveendran Committee appointed in 2012 by the Supreme Court, the Lakshadweep Coastal Zone Management Authority (LCZMA) and the National Coastal Zone Management Authority (NCZMA), the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) finally approved the Integrated Island Management Plans (IIMPs) for all 10 inhabited islands of Lakshadweep, namely, Kavaratti, Agatti, Androth, Amini, Kadmat, Kalpeni, Chetlat, Kiltan, Bitra and Minicoy.

A gentler touch

The Maldives-like development model is not recommended for Lakshadweep as it is detrimental to the fragile ecological system of the islands and likely to devastate the islands. The multi-crore tourism project proposed by the NITI Aayog to make Lakshadweep a high-end destination is not in consonance with the larger vision statement of sustainable development of the IIMPs.

The proposed water villa projects in Minicoy, Kadmat and Suheli in collaboration with the NITI Aayog on the lines of those in the Maldives has met with vociferous protests from the community. Already, two of the inhabited islands where the villas are to be built are reeling under a water crisis.

Further, the pillars for the villas’ construction will be driven through coral rock, destroying the very resource that people visit the islands for. It is an expensive project, and hazardous to the coral reef. The floating solar panels could restrict fishermen’s access to the lagoon and affect fishing.

Moreover, the energy and water needs of such a project are of major concern. The floating panels will also get in the way of the green turtles that graze on the sea grass. Then, the artificial shading that they cast on the lagoon floor would be ‘disastrous’ for sea grass meadows and reefs. Whether the solar panels will withstand the turbulent monsoon remains to be seen.

“Lakshadweep has barely 26 islands while the Maldives has over 1,000, with more than 950 of them uninhabited. The population density there is therefore half of what it is in Lakshadweep. Hence they have ample area to spare to indulge in all kinds of tourism development activities. For one, the Maldives is a separate country and due to a lack of alternative economic options has had to rely on and invest heavily in tourism. Whereas this is not true for Lakshadweep, which exists as a part of India and can thus be reliant on many other economic opportunities without having to subject its fragile areas to the burdens of tourism,” asserts Menon.

The tourism route taken by the Maldives has not translated into a great quality of life for the local populace. International tourism businesses are the ones raking in most of the profits — some statistics suggest nearly 60 percent of employees in the different resorts are foreigners, meaning even employment opportunities are few and far between for the locals.

“Society for the Promotion of Recreational Tourism and Sports (SPORTS), a nodal agency of Lakshadweep Administration constituted for the promotion of tourism in Lakshadweep, should continue their package tours like Samudra, covering Kalpeni, Minicoy and Kavaratti, and also air packages to Kadmat, Bangaram and Thinnakkara,” urges Ranjan Abraham, MD, Clipper Holidays, a licensed travel agent who has been promoting Lakshadweep for more than 25 years. Now these trips have been suspended due to the spread of COVID-19 in the islands.

But the regulations introduced by the new administration intend to aggressively push for tourism development across all islands, and are likely to further the agenda of the controversial lagoon villas for Minicoy, Suheli, Cheriyakara and Kadmat, which had been introduced through the Tourism Policy document of 2020. Expansion of tourism is also likely to bring with it concerns about waste disposal, strain on freshwater supply, reef damage and other issues.

In 2014, the Justice R.V. Raveendran Committee, appointed to evaluate the IIMPs, made some strong recommendations which are now part of the IIMPs. It is “highly essential to protect corals, sea grass and other ecosystems from anthropogenic activities,” the report said, going on to list activities such as waste disposal, port development, dredging of navigational channels, construction of breakwaters, tourism and related activities, sand mining, and intensive fishing. The paucity of potable water and the delicate water table would lead to depletion of potable water availability for the islanders. The committee emphasized that sensitization of officials and education of the islanders to create awareness about the fragile ecology of the islands and the need for conservation of the corals, lagoons and other ecosystems should be taken up on priority. As part of such education and sensitization, there should be emphasis on the need for reduction of polluting motor vehicles, conservation of water and energy, creation of non-polluting alternative sources of energy and of efficient non-polluting sewage disposal.

Comments

-

Chandralekha Anand Sio - July 7, 2021, 6:53 p.m.

The voice of the inhabitants should be heard in making any decisions regarding making Lakshwadip a tourist destination.

-

Shamantha DS - July 7, 2021, 1:20 p.m.

As usual Susheela Nair's unique perspective towards tourism is brilliant.