Mass appeal: Teeming crowds at a Modi election rally | Money Sharma/AFP

Poor put faith in powerful Modi

Sanjaya Baru

The common perception about Narendra Modi’s first term as Prime Minister is that he was first elected in 2014 on a platform of development and has since been re-elected, in 2019, on the platform of Hindutva nationalism. On the contrary, Modi’s consistent political platform is best described as Developmental Hindutva. He has been able to widen the political support base for the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) core ideology of Hindutva by focussing on the tried and tested mainstream Indian political narrative of “growth with social welfare” (Indira Gandhi), “growth with social justice” (Janata Party) and “growth with a human face” (Narasimha Rao - Manmohan Singh).

The verdict of May 2019 is, therefore, best described as a vote for Narendra Modi’s brand of Hindutva with its emphasis on social and economic development and nationalism. The difference is that Modi personalised that experience by entering a poor household’s kitchen, by installing a toilet nearby and letting the poor know he is battling the rich on their behalf.

The verdict of 2019 marks a tectonic shift in Indian politics taking forward a trend that began almost two decades ago with the decline of the Indian National Congress and its gradual replacement by the BJP as India’s natural and national party of governance. The BJP is no longer a fringe party grabbing the political centre. That was and remains the position of the various Communist parties even when the undivided Communist Party of India (CPI) was the largest single national opposition party in the Lok Sabha of 1952 to 1967. Even as the original CPI tried to move to the political centre, under the leadership of S.A. Dange, the CPM and CPI(ML) broke away taking the bulk of the Left to the sidelines of national politics, leaving the centre to be occupied by the Congress and its many splinters.

As the Congress’s hold over the centre weakened and the Left remained regionally and politically confined, that centre space of Indian politics was then occupied by a clutch of caste-based and regionally confined political parties. Through the 1980s and 1990s the BJP, a fringe ‘right-wing’ party at the time, challenged both the Congress and the caste-based parties, while aligning with various regional parties (Telugu Desam, the Tamil parties, Akalis, Trinamool Congress, Biju Janata Dal, Shiv Sena and so on). The BJP’s first priority was to replace the Congress as a national party. Second, it had to decimate the caste-based parties (Lalu Prasad Yadav, Mulayam Singh, Mayawati, Ajit Singh, and so on). This is precisely what it managed to achieve over the past decade.

Entering the campaign for 2019 the BJP had to move on the third and final front of challenging ‘regional’ parties, once its allies. It has succeeded in that effort in West Bengal, made a dent in Telangana and Odisha, but has so far failed in Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Going forward, the BJP will seek to gain ground both in Odisha and Telangana where the existing regional parties in power are excessively dependent on the personality of the incumbent leader. Kerala may remain outside the BJP’s reach, like Punjab, for some time to come.

This political evolution and expansion of the BJP has been made possible by its platform of Developmental Hindutva, with development defined not just as economic growth, but in terms of a variety of social policies that have made the government the source of livelihood security and betterment for many citizens. Note the fact that Modi has adopted most of the ideas of social development that came out of Sonia Gandhi’s National Advisory Council (NAC) and introduced new ones of his own like Ayushman Bharat that give the State a larger role in civil society.

In pursuing this model of paternalistic development, where the State rather than the market once again becomes the source of livelihood security, Prime Minister Modi has reverted to the pre-neo-liberal model of government-supported development. In many ways this is in keeping with a trend around the world where the State has returned to play a larger role in economic development. From Donald Trump’s America to Xi Jinping’s China and across Europe, citizens are expecting more from the State than they did during the era of neo-liberalism.

Those who imagined that Modi’s ‘right-wing nationalism’ would also mean ‘right-wing’ free market economics have been disappointed. Modi, like Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump, is a believer in the power and the role of the State. Hence his commitment to paternalistic development. Modi brings gas stoves into your home. He brings electricity to your village. He builds toilets for you. He is the provider. The mai-baap of a 21st century sarkar.

With economic growth slowing down globally and world trade, too, governments around the world are being expected by their voters to do more. State capitalism is making a comeback as markets fail to provide answers to structural changes brought about by demographic shifts, technological change and geopolitical rivalries. In the era of geo-economics the government is expected to steer the economy. Modi has won the trust of the Indian voter as a reliable captain who can steer the ship of the Indian economy and polity through uncertain waters. What then are Prime Minister Modi’s priorities as he begins his second term?

Women cheer Modi in West Bengal

Women cheer Modi in West Bengal

Priority 1: The economy

In an assessment published last week the Paris-based Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) — the rich countries’ club — saw national income growth in India in 2019-20 to be around 7.5 per cent. “This growth will come from higher domestic demand due to improved financial conditions, fiscal and quasi-fiscal stimulus, including new income support measures for rural farmers, and recent structural reforms. Lower oil prices and the recent appreciation of the rupee will reduce pressures on inflation and the current account.” Underscoring the fact that India would still be among the G20’s fastest growing economies, the OECD observed, “Investment growth will accelerate as capacity utilisation rises, interest rates decline, and geopolitical tensions and political uncertainty are expected to wane.”

Not everyone would share this optimism. Not only is the global economic environment expected to become more challenging as the United States- China trade war continues, but even the geopolitical environment around India may get destabilised if the US injects more instability into West Asia. Clearly, Prime Minister Modi’s Priority Number One will remain macro-economic management. The fiscal assumptions and forecasts made in the interim budget, presented by interim finance minister Piyush Goyal this February, must hold. Given the sweeping mandate received, Modi can afford to go slow on some of his fiscally demanding promises. It is quite normal for governments in democracies to turn fiscally conservative after an election, ensuring that the political business cycle gets turned down.

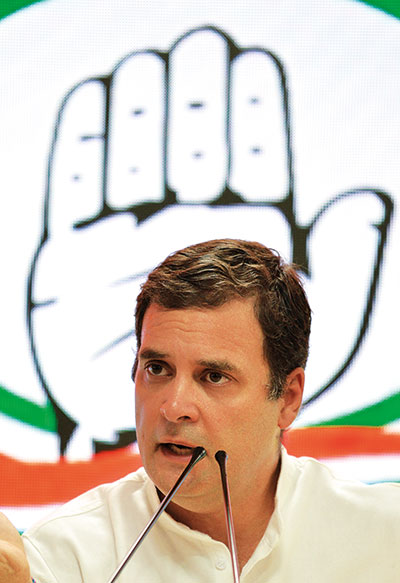

Rather than boost growth through public spending, the government should aggressively pursue ease of doing business, reversing the highly arbitrary functioning of various regulatory agencies, including the Securities and Exchange Board of India. The Indian private sector requires a more sympathetic hearing from the second Modi government. At least one reason why Rahul Gandhi appeared larger than his real self over the past year has been because of the support he has been getting from small, medium and even big business who have been unhappy with various measures of the Modi government. It was politically sensible for Modi not to be seen worrying too much about their concerns at a time when his electoral prospects depended on wooing the poor and the middle class. But now that he is firmly in saddle, he should pay more attention to them.

An early initiative could be in increasing the pace of the Make in India programme in defence manufacturing. India’s first industrial era, in the 1930s, was based on the growth of agro-processing industries like cotton textiles and sugar. It’s second industrial era, in the 1950s, was based on the growth of public sector capital goods industries. The third industrial era of the 1980s and 1990s was based on the growth of consumer durables, including automobiles. The share of manufacturing in national income has stagnated over the past decade and a half at around 16 per cent. Both the Manmohan Singh government and the first Modi government tried their best to increase the pace of manufacturing growth but have largely failed. Given the flattening out of demand for consumer durables it is possible that many of the existing industrial sectors may face slow growth till demand picks up in the next cycle. What can be attempted in the interim is a rapid escalation of investment in defence manufacturing.

There is industrial growth to be attained by boosting the income of farmers and the lower middle class whose desire for manufactured goods, ranging from farm equipment to household gadgets, remains unsatiated, indeed unaddressed. Management guru C.K. Prahalad asked businessmen to seek ‘fortune at the bottom of the pyramid’. The financial media continues to focus on declining demand for automobiles. There may be a bigger market for a range of less sophisticated manufactured products.

Priority 2: Socially inclusive politics

The verdict of 2019 has meant that the BJP has replaced the Congress as the natural and national party of government. However, for it to govern as such the Modi government must take visible measures to win the confidence of the Muslim community. This is not about minority appeasement. This is about credibly reinforcing the message of sabka saath, sabka vikas. Prime Minister Modi’s post-victory tweet that said, “Together we will build a strong and inclusive India”, is, therefore, of great value and importance. His government and party must get the message loud and clear. The BJP must end its obsession with individual food habits and social choices.

Priority 3: Education and health

An important plank of the 2019 campaign was Modi’s healthcare initiative. He must remain focused on healthcare for all as a national objective. The government must address the concern that its policies are neither helping the needy poor nor supporting healthcare providers. A socially and regionally broad-based national public health and healthcare programme is still waiting to be implemented.

If there is one area in which India truly lags behind all the highly performing economies of East Asia, including China, it is education. A report on education reform is waiting to be unveiled. In his first term, Modi allowed his party’s ideologues to mess around with education and educational institutions. This has not served the national interest. In his second term, the PM must focus on bringing India’s educational system up to speed with the needs of the 21st century.

Priority 4: foreign policy

A Prime Minister’s main area of policy initiative at all times remains national security and foreign policy. Even in the realm of economic policy, a PM has to work with other ministers, especially the finance and commerce ministers and the ministers responsible for infrastructure development. It is, therefore, not unusual for PMs to devote greater attention to national security and foreign affairs. Both fronts remain challenging. A stronger economic performance can help increase the space for foreign policy initiatives. Hence, the economy remains a priority even in foreign policy management. With the global economy passing through difficult times, building meaningful coalitions that enable India to remain focused on her economy remains a foreign policy priority.

In foreign policy the past is no guide to the future. India needs a more forward-looking foreign policy for the 21st century. Modi has done well to maintain a balance in India’s relations with the US, China, Russia, European Union and Japan, not getting drawn into the US-China spat and strengthening strategic relations with technologically advanced nations like Germany, Japan and South Korea. This policy must continue. Closer home, sooner rather than later, Modi will have to focus on Pakistan. What India can achieve with Pakistan is a different matter. But India should at least converse with Pakistan. This remains a major gap in Modi’s first term.

The Indian electorate has been exceedingly generous to Prime Minister Modi. It has given him a handsome mandate the likes of which India has not seen in normal times for close to half a century. After all, the Congress victory of 1984 was a consequence of Indira Gandhi’s assassination. In 2019 Mr Modi has won an impressive victory in a normal year. He owes it to the people of India to give them five years of peace, livelihood security and hope for the future.

The BJP took on former ally Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal

The BJP took on former ally Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal

What about the Sonia Congress?

In my book, The Accidental Prime Minister, I argued that the UPA victory of 2009 was an endorsement of five years of the first Manmohan Singh government (2004-09), but the Sonia Congress gave most of the credit for that victory to Sonia and Rahul Gandhi. The complete takeover of the Indian National Congress, which became the Indira Congress in 1969 and the Sonia Congress in 1999, by the Nehru-Gandhi family culminated in the overnight elevation of Priyanka Gandhi Vadra as the party’s general secretary virtually on the eve of the 2019 elections.

The verdict of 2019 has finally exposed the utter bankruptcy of the Nehru-Gandhi brand. The combined number of MPs in the Lok Sabha belonging to parties that broke away from the Congress — YSR Congress, Trinamool Congress, Nationalist Congress and a few individuals who went to other parties — is almost the same as the number of Sonia Congress MPs elected this time.

The verdict of 2019 has finally exposed the utter bankruptcy of the Nehru-Gandhi brand. The combined number of MPs in the Lok Sabha belonging to parties that broke away from the Congress — YSR Congress, Trinamool Congress, Nationalist Congress and a few individuals who went to other parties — is almost the same as the number of Sonia Congress MPs elected this time.

Given this fact, the only way in which the erstwhile Indian National Congress can revive itself is for all the breakaway factions of the Congress to come together and form a single party under a new leader. Clearly, Rahul Gandhi cannot be that leader having failed repeatedly to deliver a victory in New Delhi. The new group will have to reinvent the Congress for the 21st century under a new, democratically elected leader. It will take at least three to four years for this process to be completed. If a new Congress, liberated from the stranglehold of those who led it to two defeats, emerges by the time of the next Lok Sabha it can hope to put up a decent fight against the BJP and at least claim the empty seat of the Leader of the Opposition in Parliament.

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and Distinguished Fellow, Institute for Defence Studies & Analysis in New Delhi

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!