Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, organisers of the festival | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Watching films in the clouds

Saibal Chatterjee, Dharamshala

In the run-up to its eighth edition, the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF) ran into a roadblock. The expected funds weren’t forthcoming: not unusual for an independent cinema showcase that is uncompromising in its vision, pretty much like the films it celebrates. The response that the prospect of cancellation prompted was, however, anything but usual.

DIFF 2019 nearly did not happen. In September, with sources of funding drying up, festival directors Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, a filmmaking couple who envisaged the annual event as a gift of gratitude to the people of the hill town they have lived in for over two decades, felt they had reached the end of the road and that it would be impossible to pull off their labour of love one more time.

Two months on, DIFF 2019 was rolled out without a hitch thanks to the unstinted support and encouragement that the duo and a team of dedicated festival volunteers received from their long-time well-wishers — individuals and organisations based in Dharamshala and the rest of the country. Solidarity of like-minded people played a key role in pulling the film festival from the brink.

With its complement of acclaimed narrative features, documentaries and short films, DIFF 2019 offered a wide palette of cinematic riches over four days of screenings. The programme, in keeping with the core spirit of the festival, was dominated by deeply personal non-fiction films and path-breaking reality-inspired tales from globally feted directors.

Visitors to the festival enjoy a break in the sun | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Visitors to the festival enjoy a break in the sun | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Filmmakers whose latest works were screened in Dharamshala this year ranged from Portugal’s celebrated Pedro Costa (Vitalina Varela) to first-timers like Palestine’s Bassam Jarbawi (Screwdriver) and Peru’s Melina León (Song Without a Name). Among other feature-length dramas in the DIFF 2019 line-up were the Macedonian film God Exists, Her Name is Petrunya, a feminist religious satire helmed by Teona Strugar Mitevska, and Iranian director Ali Jaberansari’s sophomore effort, Tehran: City of Love.

French New Wave pioneer Agnes Varda’s final film, Varda by Agnes, a documentary offering insights into her formidable oeuvre through excerpts from her films, was one of the highlights of the festival. Varda passed away in March 2019 at the age of 90 soon after completing this introspective cinematic essay.

DIFF also laid out a wonderful spread of documentaries — from the devastating For Sama, a Syrian filmmaker’s letter to her daughter born amid the battle of Aleppo to Kazuhiro Soda’s Inland Sea, an elegiac black and white exploration of a declining Japanese village located near the Seto Island Sea.

Cinema unplugged

Adil Hussain, an actor who has worked in Hindi commercial productions as well as low-budget independent films in many Indian languages besides high-profile international movies, says: “DIFF is India’s best film festival for the simple reason that its emphasis is not on the stars but on cinema. Had it focused on individuals rather than on the films that it programmes, its purpose would have been defeated.” Supporters of DIFF have never had reason for worry on that count.

In the catalogue of the inaugural edition of DIFF in 2012, the festival directors had written: “Among the many reasons that impelled us to finally try and make this dream (of staging a film festival in Dharamshala) a reality, two stand out: we wanted to give something back to the place we had made our home; and we wanted to create a truly international event that all communities that live in Dharamshala could participate in and be proud of.” This year’s edition left nobody in any doubt that this is an event worth fighting for.

Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam mingle with attendees | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam mingle with attendees | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Funds certainly weren’t aplenty, but the unwavering commitment that had propelled DIFF’s previous seven editions were on full display. The budgetary cutbacks that were visible in certain areas of the festival did not take the sheen off the quality of the cinema that was on view from November 7 to 10. Some of the films were, as always, handpicked by Sarin and Sonam. Others came (a first for DIFF) via submissions made on FilmFreeway. Both selections reflected a level of critical discernment that lends the festival its unique character.

DIFF returned, after a three-year hiatus, to the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), where it had all begun in 2012. The main auditorium, now a sturdy structure with full-fledged film projection facilities, was a completely transformed space. The grounds of TIPA also had a portable movie theatre courtesy Picture Time, a company that puts up mobile digital screens at short notice. A smaller auditorium on the premises screened DIFF’s programme of short and children’s films and received a heartening response from the audience.

Nowhere were the footfalls more apparent than in the acting masterclass conducted by Adil Hussain. It was a Sunday. The interaction was set to take place in TIPA’s smallest auditorium. But so overwhelming was the demand for seats that the masterclass had to be shifted to the spacious terrace. It was a ‘sold out’ show.

This was the second such DIFF event in three years featuring Hussain. In 2017, the actor was in Dharamshala with two of his films — debutant Shubhashish Bhutiani’s Mukti Bhawan and Iram Haq’s Norwegian drama What Will People Say. There is something about DIFF that enthuses anyone who makes the trip to the capital of the Tibetan diaspora to keep coming back for more.

Hussain attended DIFF in 2014 as well. That was the year of Partho Sen-Gupta’s Sunrise, an Indo-French co-production that had the actor in the role of a father grieving the abduction of his daughter and looking for her many years later. Has he seen any changes in DIFF? “It has improved,” he replies. “It is better organised now.”

Well-known actor Adil Hussain's class in acting | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Well-known actor Adil Hussain's class in acting | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

The DIFF organisers weren’t the only ones happy with the way things turned out this year. “People stepped up and offered to help to keep DIFF running,” said Sarin who, with Sonam, has been travelling around the world with their second narrative feature, The Sweet Requiem, since its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2018. “This year, the public participation in the festival has been greater than in the past.”

At the end of DIFF 2019, this is what Sarin had to say in a Facebook post: “This was a memorable edition. We had record audiences who packed all three venues, engaged in thoughtful Q&As with the directors and generally had a great time…” Talk of thriving when the chips appear to be down.

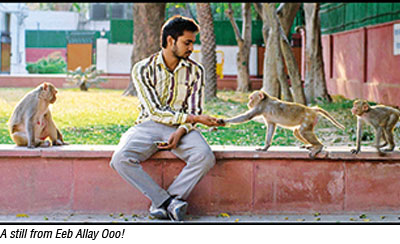

Until last year, a part of DIFF’s funding came from the Himachal Pradesh government departments of tourism, and language, arts and culture. This year was different. “It was a crunch situation and we had no option but to take a call on whether we could continue with the festival,” said Sarin. Once the show began — Prateek Vats’ Eeb Allay Ooo! was the opening film of DIFF 2019 — the creases were gone for good.

Monks strike a pose at the festival | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Monks strike a pose at the festival | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

On the first two days, the weather was fickle and a lot of rain was dumped on Dharamshala. On November 9, the festival woke up to a gloriously sunny day. The final day was no different. It was as if the weather gods were in complete sync with the mood on the ground as DIFF unspooled its slate of memorable films.

Asked which of the films in his selection he particularly liked, Sonam said: “My favourites are Tehran: City of Love, a triptych of stories of the sort of characters we rarely see in Iranian cinema, and (Portuguese director) Pedro Costa’s masterly Vitalina Varela.”

Opening film

Eeb Allay Ooo!, which arrived in Dharamshala after its world premiere in the Pingyao International Film Festival and a subsequent screening in the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival, transported the audience to New Delhi’s Raisina Hill and its surrounding VIP zone where a migrant, Anjani (Shardul Bhardwaj), is hired on contract by the government to rid the offices and homes of the high and mighty of marauding macaques.

The young man, a replacement for langurs whose employment for the purpose of scaring away monkeys has been stymied by animal rights concerns, is required to mimic the aggressive simian breed. Inevitably, his personal dignity is quickly compromised and degradation sets in. The biting satire at the heart of Eeb Allay Ooo!, which is at once deadpan and acerbic, emerges from a free blend of fiction and truthful cinema.

DIFF’s opening films over the past years — Hansal Mehta’s Shahid (2012), Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox (2013), Rajat Kapoor’s Aankhon Dekhi (2014), Kanu Behl’s Titli (2015), Raam Reddy’s Thithi (2016), Shubhashish Bhutiani’s Mukti Bhawan (2017) and Dar Gai’s Namdev Bhau: In Search of Silence (2018) — tell a story in themselves. They, and all the other films that have played here, vindicate the festival’s steadfast commitment not only to showcasing high quality independent cinema but also to promoting up-and-coming filmmaking talent around the country and the world.

Let us cast our minds back to what the two festival directors had written in DIFF’s first catalogue in 2012: “The digital revolution that is shaking the traditional cinema industry has also sparked an explosion in independent filmmaking… These films have to be shown somewhere — and all filmmakers, at heart, dream of their work being projected onto large screens before captive audiences.”

Let us cast our minds back to what the two festival directors had written in DIFF’s first catalogue in 2012: “The digital revolution that is shaking the traditional cinema industry has also sparked an explosion in independent filmmaking… These films have to be shown somewhere — and all filmmakers, at heart, dream of their work being projected onto large screens before captive audiences.”

“In India, which has never had a distinct art-house culture, it is rare for independent films to appear in commercial movie halls. Thus, film festivals are the only viable options… Yes, film festivals like DIFF will not only live on but even multiply. Sparked by the bold vision of new filmmakers, they will increasingly become oases of communal sharing and an open exchange of ideas. That, at least, is our hope!”

Hope still lingers. Confidence has taken a bit of a beating. But Sarin and Sonam are filmmakers who know how difficult the game is for those who operate outside the pale of the commercial movie industry. They are also artists and independent cinema activists driven by extraordinary tenacity and a sense of purpose, attributes that stand them in good stead as the driving forces behind DIFF.

Fourteen years separate their first narrative feature, Dreaming Lhasa (2005), and their second, The Sweet Requiem (2018), but they have kept chipping away not only for themselves, but also for all filmmakers of their ilk toiling away in different parts of India to stay in circulation.

Besides The Sweet Requiem, which was in the DIFF 2018 line-up, Sarin and Sonam’s feature-length documentary When Hari Got Married screened in the first edition of DIFF alongside Umesh Vinayak Kulkarni’s Marathi film Deool, Ashim Ahluwalia’s premiered-in-Cannes title Miss Lovely, Dibakar Banerjee’s political thriller Shanghai and Rajan Khosa’s children’s film Gattu.

Sustained quality

In its first year, DIFF also showcased Korean director Hong Sang-soo’s Hahaha and Japanese maverick Takashi Miike’s Hara Kiri: Death of a Samurai, besides acclaimed documentaries such as Wim Wenders’ Pina, Asif Kapadia’s Senna and Patricio Guzman’s Nostalgia for the Light. It was as formidable a kick-off as any that a new festival could have bargained for.

DIFF has sustained itself as a platform for Indian indies: Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox, Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court, Geetu Mohandas’ Liar’s Dice, Gurvinder Singh’s Chauthi Koot, Ruchika Oberoi’s Island City, Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan, Vetri Maaran’s Visaaranai, Rima Das’ Village Rockstars, Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton and Aijaz Khan’s Hamid, among numerous others.

DIFF has sustained itself as a platform for Indian indies: Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox, Chaitanya Tamhane’s Court, Geetu Mohandas’ Liar’s Dice, Gurvinder Singh’s Chauthi Koot, Ruchika Oberoi’s Island City, Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan, Vetri Maaran’s Visaaranai, Rima Das’ Village Rockstars, Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton and Aijaz Khan’s Hamid, among numerous others.

Consider the documentaries that DIFF has programmed in the past — Anand Patwardhan’s Jai Bhim Comrade, Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Art of Killing and The Look of Silence and Amit Virmani’s Menstrual Man — and you know exactly why the festival draws film lovers to the mountains.

Returning to the 2019 fare, first-time director Kislay’s drama Aise Hee (Just Like That), former Bir resident Gurvinder Singh’s Khanaur (Bitter Chestnut) a hybrid of the real and the staged, and American director Jesse Alk’s debut documentary feature Pariah Dog, a remarkably insightful and entertaining look at a handful of individuals who have devoted their lives to the care of street dogs in the city of Kolkata, were among the talking points.

Aise Hee, set in Allahabad, homes in on a recently widowed septuagenarian who defies societal norms by deciding to live for herself for a change. She stops going to the temple, visits a shopping mall to have ice-cream, strolls along the river bank, befriends a beauty parlour girl and seeks the help of a Muslim tailor to teach her embroidery.

Not surprisingly, her ‘rebellion’ isn't appreciated by the neighbours, who keep reminding the family how respectable her deceased husband was, and the family of her son, a reporter who works on contract for All India Radio. The film unfolds in a city in flux in more ways than one but when it matters it embraces changes that bring out the worst in its people.

Not surprisingly, her ‘rebellion’ isn't appreciated by the neighbours, who keep reminding the family how respectable her deceased husband was, and the family of her son, a reporter who works on contract for All India Radio. The film unfolds in a city in flux in more ways than one but when it matters it embraces changes that bring out the worst in its people.

Khanaur, too, is about change, but the ‘story’ plays out in Bir and Barot in Himachal Pradesh, where a 17-year-old café employee caught between the region’s traditional occupations — the boy is a carpenter’s son who doubles as a cowherd when needed — and the growing desire to venture forth into the wider world. It is a film in which the actors play themselves, including the café owner Monisha Mukundan.

The Himachal story

Significantly, it isn’t just filmmakers in the traditional production centres who have benefitted from the amplification that DIFF provides to fresh cinematic voices. Filmmakers in Himachal Pradesh, where cinema is still a fledgling entity, have also begun to show signs of being enthused by the exposure that they have gained since DIFF showcased local director Sanjeev Kumar’s Dile Ch Vasya Koi, the story of a young man who works in a slate mine high in the mountains, in its first year itself. In 2016, the same filmmaker was back at DIFF with Mane De Phere (Circles of the Mind).

The DIFF Fellows programme, launched in 2014 to promote filmmaking talent in the Himalayan regions of India, has already begun to bear fruit. It has yielded at least two filmmakers from Himachal Pradesh who are working on their first feature films — Rahat Mahajan and Siddharth Chauhan.

Mahajan was a DIFF fellow in 2018 and a native of Nurpur, the year the festival selected only filmmakers from Himachal Pradesh for the programme. A former Vishal Bhardwaj assistant, he spearheaded the visual promotions of films like Kaminey, Ishqiya and Udaan and has several short films to his credit.

Chauhan, who was a DIFF fellow a year earlier and had a short film (Pashi) in the festival last year, lives and works in Shimla. The 29-year-old filmmaker is currently shooting his first feature, Amar Colony, in his hometown. Two key impulses inform Chauhan’s approach: one is to create opportunities for locals and his friends in Shimla; the other is to ensure that his films go beyond the superficial and engage the audience in a way that enriches them.

Manali-based social anthropologist and aspiring filmmaker Kesang Thakur, who was a DIFF fellow last year, is in the midst of making a documentary co-directed by her Italian husband — “he is a trained filmmaker,” she says. What is the film about? It is, she says, “about me trying to understand Lahaul Valley”.

Manali-based social anthropologist and aspiring filmmaker Kesang Thakur, who was a DIFF fellow last year, is in the midst of making a documentary co-directed by her Italian husband — “he is a trained filmmaker,” she says. What is the film about? It is, she says, “about me trying to understand Lahaul Valley”.

“The first time I came to the festival, I was studying,” she says. “The films I watched opened my eyes to the potential of cinema as a vehicle of communication.” Thakur's research work is focussed on the lives of people of the trans-Himalayan region and she hopes to use the medium of cinema to document the stories she is in the process of gathering.

Is there anything that she feels that DIFF still lacks? Says Thakur: “I would like greater participation by local people. Many residents of Dharamshala do not know whether they can access this space. That needs to change.”

Sarin, on her part, believes that “we need to involve more people and widen the base". Community outreach has been an important DIFF activity. As part of its plan to take cinema around, DIFF holds community screenings in and around Dharamshala, besides inviting local college and school students to be part of the festival. For the 2019 edition, invitations were extended to 250 students from ten local institutions.

Children’s films

With curator Monica Wahi coming on board, DIFF began to screen children’s films in 2015. It increased the festival’s outreach among school children, many of whom have been regularly attending DIFF. “The same children have been watching these films for five years,” says the Mumbai-based Wahi. “I can, therefore, challenge more than I would at other festivals.”

Vinod Kamble’s Kastoori, the story of a Dalit boy who cleans toilets, buries the unclaimed dead and performs post-mortems to fund his education, is a measure of the extent the children’s films curator can go in Dharamshala. The protagonist of Kastoori is taunted by his schoolmates for the stench that clings to him, causing him to launch a search for kastoori (musk) in the company of a friend (who is a butcher’s son) to mask the smell that makes him an object of ridicule.

Kastoori isn’t a children’s film in the strictest sense of the term. Its selection by Wahi points to the confidence she has in her audience as well as to the need for cinema to raise disturbing questions and bring children face to face with the harsh reality of the caste system. This is precisely what separates DIFF from other film festivals in India: it does not shy away from letting children process difficult themes.

Kastoori isn’t a children’s film in the strictest sense of the term. Its selection by Wahi points to the confidence she has in her audience as well as to the need for cinema to raise disturbing questions and bring children face to face with the harsh reality of the caste system. This is precisely what separates DIFF from other film festivals in India: it does not shy away from letting children process difficult themes.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!