Kantara, the blockbuster success from Karnataka

South sets the pace

Saibal Chatterjee

BOLLYWOOD had expected fans to return in hordes to the multiplexes in 2022. They did rush back for the theatrical experience but not for the movies whose makers had pinned their hopes on a post-pandemic, back-to-business-as-usual run. A string of big-budget Mumbai films struggled to find takers. The void was filled by films from the South: RRR, KGF 2, Pushpa and Kantara.

The Bombay industry was plunged into disarray. The growing panic was best illustrated by the events that followed the October release of the teaser of the upcoming mythological extravaganza, Adipurush. Based on the Ramayana and starring Prabhas and Saif Ali Khan as Rama and Ravana, respectively, the movie, reportedly the most expensive ever made in India, promised eye-popping visual effects. What viewers got instead in the teaser was tacky computer-generated imagery. They gave vent to their disappointment on social media.

The director of Adipurush, Om Raut, alarmed at the flak the teaser received, deferred the release of the film by six months — from January 12 to June 16. It was time to return to the VFX machines and initiate a salvage operation. Raut admitted as much but to earn the brownie points that many Mumbai filmmakers have been chasing in the last few years, he declared grandly on Twitter: “Adipurush is not a film but a representation of our devotion to Prabhu Shri Ram and a commitment towards our sanskriti (heritage) and history.”

Raut’s explanation reflected not only a narrow notion of “our sanskriti”, but also complete ignorance of the fact that there is a substantial difference between history and mythology, something that many Mumbai film producers prefer to ignore in order to curry favour with the ruling dispensation.

All the reverses notwithstanding, it wasn’t a wasted year for Indian cinema. Away from the hurly-burly of commercial Hindi cinema, 2022 began with Writing With Fire, directed by Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas, earning an Academy Award nomination in the Best Documentary Feature category.

Early in the year, Delhi-based filmmaker Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes won the Grand Jury Prize in the World Cinema Documentary competition of the Sundance Film Festival. In May, the film added another major triumph to its list of accolades — the Cannes Film Festival’s Golden Eye Prize for the best documentary.

Writing With Fire is about a newspaper run by Dalit women in Uttar Pradesh. All That Breathes, which establishes a metaphorical parallel between Delhi’s severe air pollution and the rise and consequences of divisive politics, is about a pair of Muslim siblings who rescue and save injured black kites that fall from the city’s smoggy skies.

Pan Nalin’s Gujarati-language Chhello Show (Last Film Show), an ode to cinema of the pre-digital era, was deservedly picked as India’s official submission for the best international feature Oscar.

|

|

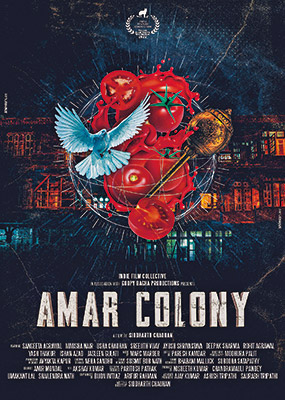

Amar Colony got international accolades |

The year ended with young Shimla filmmaker Siddharth Chauhan’s Amar Colony bagging a Special Jury Prize at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival. So, independent Indian cinema did enough in 2022 to keep the flag flying.

When Adipurush hits the screen in mid-2023, it might prove detractors wrong but the storm it has run into and the filmmaker’s response to the kerfuffle sum up what large swathes of the Mumbai movie industry are up to: serving the agenda of hyping India’s past in keeping with a majoritarian political ideology.

In light of the above, consider the sorry fate that befell big films like Samrat Prithviraj and Ram Setu, both starring Akshay Kumar. They arrived in the multiplexes amid great fanfare but did not create so much as a ripple. The makers of the two films learnt the hard way that it is far easier to falsify history and peddle pulpy myths than to inveigle today’s audiences into buying into unabashed claptrap, especially when it is aggravated by incompetence.

Akshay Kumar, who delivered other resounding duds in 2022 (Bachchan Pandey, Raksha Bandhan) was by no means the only A-list Mumbai movie star who suffered debacles. Ranbir Kapoor’s Shamshera sank without a trace, Ranveer Singh’s Jayeshbhai Jordaar went out with a whimper, Ajay Devgn’s Runway 34 did not take off at all and Aamir Khan’s Laal Singh Chaddha found itself in the red.

One film that did not do anything to disguise the demonization of a community with the aim of fanning hate — The Kashmir Files — mopped up huge profits but it did great damage to an industry that was once celebrated for its commitment to social harmony.

RRR was a blockbuster from the South that filled the void created by failed Bombay films

RRR was a blockbuster from the South that filled the void created by failed Bombay films

The massive vacuum created by the continued underperformance of the Bollywood biggies at the box-office was exploited to the hilt by blockbusters from down South — Pushpa, RRR, KGF 2 and Kantara. These pan-Indian hits changed the rules of the game. Bollywood suddenly realized that hyper-local themes were the order of the day.

Not that any of these South Indian films, barring the Kannada-language Kantara, had any intrinsic merit beyond their surface gloss and glitter. One might argue that the Telugu-language RRR is all the rage in the West today, getting two Golden Globe nominations. Its maker, S.S. Rajamouli has been adjudged best director of 2022 by the New York Film Critics Circle. The fact remains that it is just another manipulative, crass Indian potboiler, only flashier and louder than any Hindi competitor has ever been.

In RRR, history receives a merciless mauling. The scale and ambition of the movie are impressive, no doubt, but it devotes an inordinate amount of energy to trivializing the under-documented history of tribal resistance against the British Raj and other forces of exploitation about 100 years ago.

The nuances ingrained in the battles that marginalized communities wage or any meaningful detailing of time, place and character are beyond the ken of RRR. So, what was it about the movie that made the very elements that undermined the likes of Samrat Prithviraj and Ram Setu the reason for its enviable commercial success? Hard to put a finger on it.

In mythologizing the real struggles of real personages, RRR appropriates the struggle of forest dwellers and tribals and uses it as a mere pretext for an SFX-laden, power-packed cinematic blitzkrieg that obviates all possibility of a genuinely empathetic account of the rebellion of oppressed people.

|

|

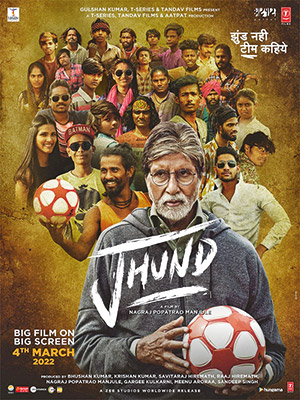

Jhund showed how the theme of caste and class oppression can be handled |

Nagraj Manjule’s Jhund, starring Amitabh Bachchan and a host of amateur actors, was at the other end of the spectrum. The three-hour film failed at the box-office but it showed exactly how the theme of caste and class oppression can be handled without turning it into a pretext for meaningless spectacle.

Jhund is a story of the walls that the socially marginalized run into, and are thwarted by, at every turn. It does away with two mythologies that form the foundation of mass entertainment in this country: one springs from the Hindu epics, the other from the dominant idioms of Indian popular cinema.

With both given a wide berth, what emerges in Jhund is a structure and a style that are embedded in the very nature of the struggle that the dispossessed are engaged in on a daily basis merely to keep their heads above water.

Jhund puts one of the biggest stars of Hindi commercial cinema front and centre and, drawing upon true events, constructs a narrative that captures a motley group of marginalized youth who, through a mix of good fortune, bold assertion and daring action, seek to break free from the life of petty crime, drug addiction and privation that they are condemned to due to social ostracism, poverty and lack of education.

Between RRR and Jhund, 2022 saw big-budget Bollywood paying a high price for underestimating an audience that has evolved since the coronavirus outbreak thanks to its exposure via the streaming services to cinema of all kinds and from diverse geographies.

The steady stream of Bollywood disasters was punctuated by stray success stories, Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2, a horror comedy, and Brahmastra Part One: Shiva, a superhero fantasy that enabled Ranbir Kapoor to live down the abominable Shamshera.

Brahmastra, which kicked off Bollywood’s first proposed superhero trilogy, has dashes of originality to go with its sweep, scale and style. That is not to say that it is perfect. Parts of it are tawdry, others are somewhat enervating. What it does well is stir up the conventions of the superhero that aren’t slavishly derivative.

The most striking aspect of Brahmastra is its firm eschewal of the kind of hypermasculinity that films of this nature usually perpetuate. With Ranbir Kapoor anchoring the action and the screenplay steering clear of the peddling of unbridled machismo, the film’s male protagonist willingly gives the woman in his life — played by the lead actor’s real-life wife, Alia Bhatt — all the leeway that she commands.

Bhatt spearheaded another of the year’s better commercial movies, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Gangubai Kathiawadi. Women of the world’s oldest profession plying their trade and fighting for justice in Bombay’s Kamathipura in the Nehruvian era are at the heart of the film.

Factual accuracy isn’t the period drama’s strong suit. But Bhansali, aided by a gifted female lead, squeezes every ounce of dramatic effect out of the script. The result is an immersive film that does not feel overly stretched even though it runs a little over two and a half hours.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Gangubai Kathiawadi was a compelling tale of one woman’s individuality

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Gangubai Kathiawadi was a compelling tale of one woman’s individuality

The visually sumptuous character study, more baroque than 1950s Bombay, is at once sweeping and intimate. With the aid of relentless drama and unwavering empathy for women sold for a song and forced to make a living in a hellhole, Gangubai Kathiawadi is a compelling tale of one woman’s individuality, tenacity and meteoric ascent to power.

Meant to be a scathing satire on patriarchy and obscurantism, Jayeshbhai Jordaar, one of many releases in 2022 from Mumbai’s top production banner, Yash Raj Films, that failed to connect with the masses, despite Ranveer Singh’s no-holds-barred performance, lacked the requisite bite.

Samrat Prithviraj, also produced by Yash Raj Films, is, expectedly, a purveyor of fanciful history draped in the glossiest of Bollywood finery. It is colourful, action-packed and laced with music but spectacularly soulless. The hollow pomp and pageantry and the shallow drama that it serves up for the purpose of pushing an expedient narrative about India’s past add up to a crashing bore.

Apart from the fact that Samrat Prithviraj, written and directed by Chandraprakash Dwivedi, plays fast and loose with facts, it reduces its principal characters to convenient caricatures, a tendency that most such Mumbai films, in their eagerness to please the masters they serve, fall prey to.

Another Yash Raj Films dud, Shamshera, was an excruciatingly bad action flick that inflicted more torture on the audience than the sadistic villain in the film does on the people he enslaves and brutalizes. After dragging the audience through two hours of absolute trash, it throws a mindless melee of a climax its way.

Shamshera, set in the second half of the 19th century, an era in which the heroine is allowed to be draped in new-millennium fabrics, throws a bundle of things into a cauldron that turns everything to ash and dust.

|

|

Laal Singh Chaddha ended up in the red |

Laal Singh Chaddha, a reworking of the 1994 Hollywood hit, Forrest Gump, wasn’t half as bad. Screenwriter Atul Kulkarni made a fair fist of the exercise. The film gave star Aamir Khan enough elbow room for expressing the emotional range of an awkward but doughty man coming to terms with the complex world around him without losing his innocence, optimism and gumption.

The principal strength of Laal Singh Chaddha stemmed from its stress on the power of hope in a time of violence and venality. Unity in diversity isn’t a particularly original idea, but its reiteration, no matter in what form, had never been more necessary.

Unlike Laal Singh Chaddha, Aanand L. Rai’s Raksha Bandhan is set in contemporary times. But it could be mistaken for a 1950s film, given its shockingly regressive ideas. Raksha Bandhan would have us believe that girls are worth nothing if they are not married and domesticated. It was headlined by Akshay Kumar (Bollywood’s poster boy of all things sanskari) who played big brother to four girls incapable of finding their way in the world.

Raksha Bandhan summed up the redundancy of Bollywood’s old ways. It was hard to believe that anybody would make a film such as this in 2022. The girls of Raksha Bandhan, like the film and the industry, were caught in a time warp.

One of the high points of 2022 was Ponniyin Selvan – Part 1. Shrinking a complex five-volume novel into a two-part movie was no mean feat. Mani Ratnam pulled it off in style. The sprawling, spectacularly mounted film is an ambitious, near-flawless adaptation of a much-loved work of Tamil literature.

Needless to say, the tale makes huge technical and artistic demands on Ratnam and his cast and crew. They prove equal to the onerous task of attaining the magnitude, the pacing and the stylistic flourishes that the story demands and available image-making technology allows.

Ponniyin Selvan: Mani Ratnam’s film is a treat for the eyes as much as it is for the mind

Ponniyin Selvan: Mani Ratnam’s film is a treat for the eyes as much as it is for the mind

Ratnam does not resort to sensory or visceral overdrive, drawing strength instead from the smart script written by him, B. Jeyamohan and Elango Kumaravel and from a cast of actors at the top of their game. PS-1 is a treat for the eyes as much as it is for the mind.

History and mythology coalesce purposelessly in Ram Setu, a cinematic abomination of epic proportions. The film occasionally cites books and other sources of knowledge to draw a convenient conclusion about the Ramayana, Lord Rama and Ram Setu that smacks of brazen mendacity.

Parts of Ram Setu, based on a story by creative producer Chandraprakash Dwivedi (who helmed Samrat Prithviraj, which was designed to serve a largely similar narrative) pretend to be science fiction. Experts are huddled in a floating laboratory aboard a ship out at sea and terms such as carbon dating, sonar imaging and global warming are bandied about. But let alone science, Ram Setu isn’t even serviceable fiction.

Light and the magic that it can create combine to serve as the leitmotif of Chhello Show (Last Film Show), Pan Nalin’s deftly crafted Gujarati-language film about a nine-year-old boy in a remote Saurashtra village who falls under the spell of cinema and finds his metier.

|

|

Chhello Show: Pan Nalin’s deftly crafted Gujarati-language film |

The film revolves around the encounters and adventures that shape the boy’s imagination. It is helped along by a cast of actors — no recognisable faces here — who merge completely with the milieu and enhance the enticing tangibility of the characters they play and the rural and urban spaces they inhabit.

The visually arresting, emotionally engaging coming-of-age tale plays out in the course of a summer about a decade ago and hinges on two decisive turning points — one that opens a door for the young protagonist, and one that changes the way films are made and delivered.

Two inventive Mumbai movies that made amends (towards the end of the year) for all the low-grade stuff that Bollywood foisted upon its fans were Amar Kaushik’s Bhediya and Anirudh Iyer’s An Action Hero. The former, filmed entirely in Arunachal Pradesh, subverted the body-horror genre to craft a tale about the man-animal conflict and the need to protect indigenous cultures and reverse the denudation of forests.

The latter tapped into the conventions of a revenge tale to construct a lively and entertaining commentary on notions of heroism, the nature of movie stardom, the scourge of media overreach and distortions of reality in a world where truth is invariably buried under an avalanche of noise, images and hysteria.

In the guise of a thriller, An Action Hero held up a meta mirror to Mumbai movies and the masses that consume them. The relationship between the two has been fraught of late. Repeated box-office failures have compelled complacent film producers to shed dead habit and return to the drawing board.

An Action Hero

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!