Living with tigers in Ranthambhore

When I first went to Ranthambhore in early 1976, seeing wild tigers was the most difficult of tasks. You could roam the forest for days and nights without ever encountering even a sign of a tiger. If we saw a fresh pug mark it was a moment to celebrate and a glimpse of a tiger even for a second was like witnessing a wonder of the world. The park then was full of villages and bullock carts that plied the tracks. Agricultural fields dotted the landscape and even near Jogi Mahal a crop field surrounded the huge banyan tree. There were no tourists and no rules.

Our first glimpses of tigers were always at night and the tiger was completely nocturnal, keeping far away from the daytime activities of man. Therefore, to encounter a tiger I had to lead a nocturnal life, sleeping most of the day and waking at sunset to explore this land of the  tiger. Most of the night and sometimes until dawn we would criss-cross the forest waiting for the alarm calls of deer to signal the movement of tigers. At the most, once or twice a month, we would feel excited and exhilarated as a tiger would flash across the road, caught momentarily in our jeep’s headlights. These sightings lasted only for a few seconds and we had to rub our eyes in disbelief to absorb what we had seen. Most of 1976 rolled by in this way and I slowly got to know and trust Fateh, who became my tiger guru. We became good friends and our friendship lasted for thirty- five years.

tiger. Most of the night and sometimes until dawn we would criss-cross the forest waiting for the alarm calls of deer to signal the movement of tigers. At the most, once or twice a month, we would feel excited and exhilarated as a tiger would flash across the road, caught momentarily in our jeep’s headlights. These sightings lasted only for a few seconds and we had to rub our eyes in disbelief to absorb what we had seen. Most of 1976 rolled by in this way and I slowly got to know and trust Fateh, who became my tiger guru. We became good friends and our friendship lasted for thirty- five years.

The period 1976-77 was a busy one for Fateh. He was in the midst of shifting and resettling villages as part of an enormous effort to prevent human disturbance in the core area of the park. My first trips to the park were full of encounters with village carts and people moving from Berda to Lakarda to the Ranthambhore Fort and then back up to Anantpura. Crops grew on the edges of the lake of Jogi Mahal, and Ranthambhore Fort boasted a village at its base. Lakarda and Lahpur were full of human activity and there was not a scent of a tiger for miles. Today all these places are the best locations for wild tigers.

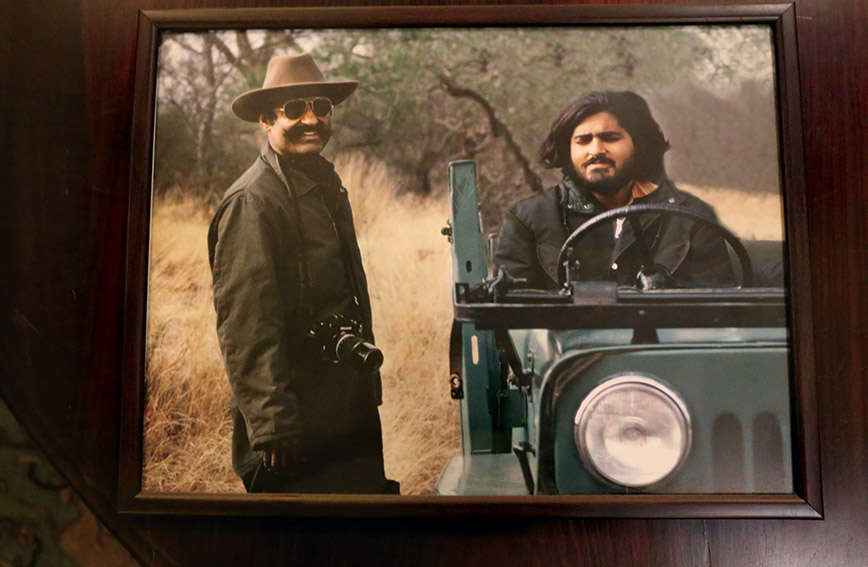

Valmik Thapar at 23 with Fateh Singh Rathore in Ranthambhore

Valmik Thapar at 23 with Fateh Singh Rathore in Ranthambhore

Fateh always said that tigers and people cannot coexist and until the villages were resettled tigers would never come into their own. He believed that this was the single most important mission to breathe life into Ranthambhore and from 1976-79 he resettled twelve villages. He was convinced that this process alone would put Ranthambhore on the world map for tigers and make it a prime destination for viewing them. He firmly believed that once the fear of man was removed the tiger would shed its nocturnal habit for a more diurnal one.

I would argue about this but in the end he was proved right. Ranthambhore began to change and in those early years, tiger sightings increased proportionally to the villages being resettled. On my third trip to Ranthambhore in 1976 the village of Lakarda had gone and the entire area had started regenerating with new grass following the monsoon. The deer and antelope were back. Herds of nilgai or blue bulls grazed on the fresh grass.

It was at the end of the first year that we became aware of the regular presence of a tigress around Jogi Mahal and in an area of 45 square kilometres up to Lakarda and Berda.We had never seen her. Tigers then were very shy and ran off if they detected the slightest human presence or the sound of a jeep. But Fateh was hopeful that one day the tigress’s pug marks would be accompanied by those of her little ones. I never thought that I would have the privilege of seeing the pug marks of cubs but Fateh was an optimist. He even believed that with cubs we would actually have a better chance of seeing the mother.

Early in 1977, while I was in Delhi, I got a telegram. ‘Come soon. Tigress with five cubs spotted.’ I couldn’t believe it. There were few records of a tigress with five cubs from anywhere on the planet. I immediately made plans to leave for Ranthambhore.

Padmini and three of her cubs amidst the black rocks of Nalghati Valley

Padmini and three of her cubs amidst the black rocks of Nalghati Valley

When I arrived at Sawai Madhopur station early that afternoon I found a jeep waiting for me. Fateh’s driver Prahlad informed me that the boss was sitting on a tree looking at a tigress. We sped off to find him. When we reached Lakarda we found a beaming Fateh sprawled across a branch of a tree. Bursting with excitement, he slowly made his way down the branches. He had been watching a tigress and her five five-month-old cubs in thick bush as they feasted on a buffalo that had turned feral, left behind by the villagers of Lakarda after their resettlement. He had already given the tigress a name — Padmini, after his daughter. Padmini was a slender and elegant tigress — her pale colour was offset by very calm eyes that seldom turned angry. She was rarely ruffled by anything. Because she was so easy and relaxed in the presence of humans all her cubs developed the same trait. This was then passed on to new generations of tigers in Ranthambhore.

The next day I had my first glimpse of Padmini from the jeep as she dragged away the remnants of a carcass into thicker bush. I will never forget that moment with Padmini. It was the first time in nearly a year that I had seen a tiger in daylight hours. Tears of joy rolled down my face and I knew this was only the beginning of a lifelong engagement that would be all-consuming in my life.

Ten days later, in the same area at dawn, we heard a cacophony of sambar alarm calls coming from deep in a valley. Fateh suggested that we crawl to the edge of the hill to see what was going on in the valley below. We left the jeep and crawled for a hundred metres. As we looked down we saw Padmini walking across the Lakarda grassland followed by her five cubs. She glanced upwards and saw us on the skyline but we were lucky to see the entire family for a full minute.

Short glimpses like this over the next month and we knew for sure that there were three male and two female cubs in the litter. We gave them names. The males became Akbar, Babur and Hamir; the females Laxmi and Begum. Akbar was the most confident and curious of the five cubs and clearly the dominant cub of the litter, followed by Babur and Hamir. Laxmi spent most of her time following her mother’s every step and little Begum was the shyest and also the last to eat as her siblings would push her away at a kill. We worried that Begum might not survive. A brood of five is very rare amongst tigers and she was getting the least to eat. A month later our worst fears were realized. Begum was no more. Nature had eased her out.

At this time in Ranthambhore live baits of small buffalo were used regularly by the park management to sight tigers and to record tiger numbers. Fateh decided that this was an opportunity to see Padmini and her family for longer spells, so baits were placed once a week for two months depending on Padmini’s whereabouts. I was under tiger training and my job was to walk out at dusk with the tracker Badhyaya and a bait and tie it wherever the tiger’s presence was the freshest.

During these risk-laden journeys on foot Badhyaya and I became very close and I learnt much from his instinctive knowledge of the language of the forest. He remained my favourite forest guard until his death in the mid-1990s. Slim and diminutive he had no fear of tigers. One evening Fateh said to me, ‘Let’s see how fearless you are.’ At about 10 p.m., after a couple of drinks, we got into a jeep and Fateh told Badhyaya to load a small buffalo in the back of the vehicle. He then turned to me and said, ‘If we find Padmini you are going to pull this buffalo out and tie it to a tree in front of her.’

My heart thudded in panic. I did not come from a ‘buffalo tying in front of a tiger’ background or family. But with Fateh you could never say no. I remember breaking out in a sweat and wishing we would never encounter Padmini. But no such luck and soon in the valley of Nalghati the searchlight encountered a row of glinting eyes. There, dazzling us, was Padmini with her four cubs, now nearly eleven months old. Fateh turned off the engine of the jeep and the lights. Silence and darkness descended. The buffalo groaned and Padmini knew that a feast awaited her.

Fateh literally pushed me out of the jeep and asked Badhyaya to push out the buffalo and hand me the rope with which it was tied. He turned the light on to the trunk of a tree and told me to tie the rope to the trunk. I saw Padmini watching us intently from 40 feet away. Paralysed by fear, I stumbled forward in a stupor and tied the buffalo to the tree trunk and fled back into the jeep where Fateh had the searchlight focused on Padmini.

She was already stalking the buffalo, her muscles rippling. When the buffalo saw the tigress it freed itself with a great pull of the rope. In my panic I must have tied a loose knot. As the buffalo fled Padmini raced in and walloped it, disabling its rear leg. Not only was Fateh training me to lose my fear of the tiger, but Padmini seemed to be training her cubs in the art of hunting. Padmini went and lay down behind a bush. Akbar and Babur moved in. For thirty minutes the three-legged buffalo defended himself valiantly, charging the two young tigers who kept retreating.

It was fascinating to watch. It was like boxers in a ring sparring without touching each other. Then suddenly Akbar leapt on the buffalo forcing it to the ground and struggled with it — much like a wrestler — until he finally found a grip on the neck. Babur joined the fray and jumped on the hindquarters. The buffalo died a slow death.

Nur with her cubs at the Ranthambhore National Park

Nur with her cubs at the Ranthambhore National Park

The cubs had much to learn. Soon they were feasting but after about forty minutes Padmini came up and coughed at them, forcing them to retreat. Then Hamir slowly made his way to the kill followed by Laxmi. Padmini controlled the feeding carefully. In between she helped herself. I was watching mesmerized and all fear of tigers had vanished. The hours rolled by. In front of us the secret lives of tigers were unfolding. In the next months as the cubs grew their feeding would be closely managed by their mother so that each cub ate alone, the first feeder being the most dominant. This prevented aggression and conflict amongst the cubs.

Most of my nights were spent watching the cubs in the Nalghati Valley. Many of these were full moon nights that made the scene around surreal. Silver, bluish light struck the forest and reflected off the tiger’s coat. Where in the world could you find this kind of natural beauty? How many had the opportunity to soak it in? I lived as if in a dream.

Padmini would go off and leave the cubs sprawled on the black rocks on the slopes of the hills. I used to watch them with a searchlight and a torch waiting expectantly for first light and a glimpse of them before they moved upwards. Akbar, the dominant male cub, would jump on these rocks to pose for us and get really close. The rest would watch from a little distance above. The setting was splendid and I got what I then considered were unique portraits of these young ones as they draped the black rocks of Nalghati. They were still basically nocturnal and wanted to vanish from our presence at first light but slowly each day they would spend a little more time watching us. Even forty years later, Nalghati is a place I frequently visit and play back incredible memories of those unforgettable times.

I think of 1977 and 1978 as the Padmini years during which we played a game of hide-and-seek with her. Our observations increased as the family slowly became comfortable in our presence. They were becoming less elusive and evasive and were shedding their nocturnal cloak just like a snake sheds its skin. This change indicated that they were reposing their trust in those who managed these areas.

Padmini was a most devoted mother and was now hunting non-stop to feed the ever growing appetite of her cubs. Her dominant cub Akbar was the most curious and always approached us first. He was also the last to leave in the mornings. He was easily recognizable, with a V-shaped mark on his cheek, and was fearless compared to his siblings. He initially associated the jeep with buffalo and food, but Fateh had slowly phased out baits from the diet as the months went by. There were plenty of night excursions to look for Padmini and her cubs and on one of these we encountered four tigers feeding on the remnants of a spotted deer. We watched them with a searchlight that was connected to the jeep’s battery.

Tigers in the marshy waters of the park

Tigers in the marshy waters of the park

Fateh did not realize that the battery was getting discharged. When we were ready to go the jeep did not start. Fateh tried everything but in vain. Finally, he suggested that we walk back. We were 2 kilometres from Jogi Mahal. With our hearts in our mouths, the four of us left the jeep in pitch darkness with tigers just 20 feet away and feeding. Fateh told us not to look back and sang film songs and ghazals for more than a half hour until we arrived at Jogi Mahal. It was an experience that I can summon up effortlessly to this day. Tigers lurking in the shadows behind us and Fateh singing, ‘Yeh raaten, yeh mausam, yeh hasna hasana, mujhe na bhulna bhulana?’ But it was experiences such as this one that helped in my understanding of tigers. Our challenge was to watch the family over a natural kill in full daylight, something that we had never seen until then.

It happened one day late in 1977 in the Semli Valley when we pulled over on a grassy verge and found Padmini grooming herself close by. In the grass two cubs were engaged in a tug of war over the remnants of an enormous spotted deer stag. It was our first sighting of them on a natural kill. The male cubs were aggressive and Akbar was at his best, getting the lion’s share. Babur and Hamir awaited their turn and even tried a tug of war with the carcass to break it into bits. Laxmi was the calmest, eating last but able to fend off her brothers.

Tigers still had memories of man and cowbells — with their association to livestock and food — attracted them. I had a bell in the jeep and one evening in Malik Talao, while waiting for Padmini’s cubs, I started ringing it. Nothing happened for a few minutes. Then suddenly Badhyaya, who was sitting next to me, said, ‘Tiger.’ I got a shock. I was outside the jeep and there was Laxmi approaching us. She was slouched low as if ready to stalk and pounce. I still remember the grass moving under her feet as she paced forward. I clicked a few photographs — they are some of my favourite ones even today — and leapt back into the jeep. She walked around the jeep to check if there was a buffalo inside!

On another occasion I was walking in Nalghati looking for a missing bait. We couldn’t see either bait or tiger and for some ungodly reason I started ringing the cowbell believing if there was a tiger it would show itself. From a few feet away a tiger leapt out of a ravine and raced over the hill. I stood petrified. The driver later told me that he thought that would be the end of me.

Our tiger sightings at this point came from hard work in the day and sometimes at night to track tigers down. In the light of what happens today the process in 1979 was unbelievable and difficult even to explain to someone who encounters tigers soon after they enter the park and believes that this is the way tigers are. What they don’t realize is that it was Fateh’s hard work over the years that created the conditions for this to happen.

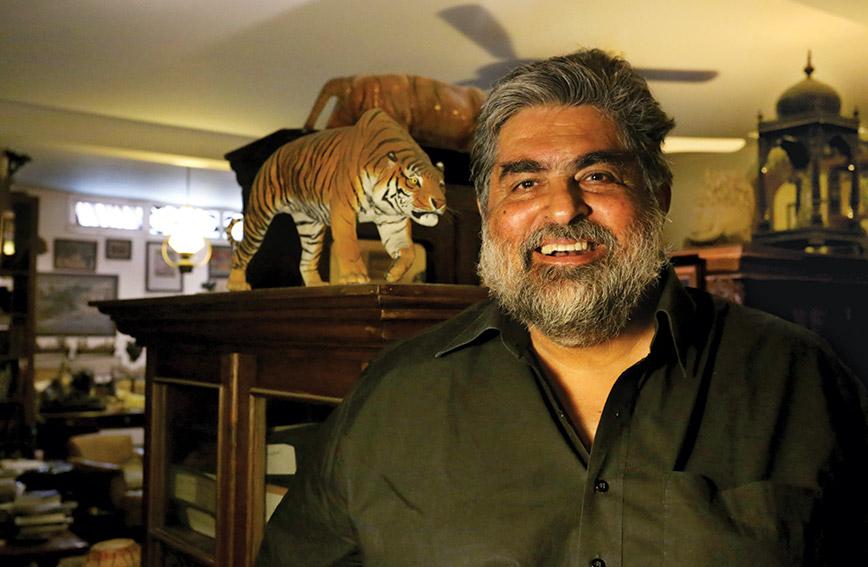

Valmik Thapar in his den

Valmik Thapar in his den

Comments

-

Abha Sharma - Feb. 22, 2023, 8:47 p.m.

Fascinating ! Enjoyed reading this.

-

Aftab Pasha - July 17, 2018, 11:04 a.m.

Written so beautifully that the reader founds itself in that jeep during the whole time. Would love to read the book. Congratulations Mr Thapar for sharing these non-believable facts and the journey of the making of Ranthambore what we see today. I hope that there are many black and white photos of that time in the book.