Rumana Jafri when she was a BDO in Kalahandi

Invisible officers make a difference

By Anil Swarup

IMAGINE the scene: villagers in the backward district of Kalahandi in Odisha are troubled by a water scarcity. They talk to their block development officers about it. One of them, a young woman relatively new to the civil service, thinks a perennial water body is the solution and sets off with the sarpanch and some others in search of such a natural source of supply. Negotiating forests and slippery underfoot conditions, she discovers water just five km away, but it isn’t what she expected. It is a beautiful waterfall! It fires her imagination and the waterfall becomes a tourist attraction, buoying the tiny local economy. As for the water the villagers were seeking, borewells are drilled to provide it to them.

In a world apart from Kalahandi, the state government of Madhya Pradesh grapples with a wholly different development problem. It is setting out to be a solar power producer. In the prevailing equations, production of solar power is the domain of central undertakings with a state merely required to provide the land.

The Madhya Pradesh project at Rewa is expected to be no different — but a 1991-batch IAS officer believes it can. With him in charge, a transformation happens. The tariff of `5 per unit falls to `2.97 per unit. A subsidy becomes unnecessary. Multiple collaborations and power purchase agreements break new ground. Solar power in India is catapulted to a new scale.

These two diverse examples have a fairy tale quality about them. You might be incredulous and well ask if this is just happenstance or really how governance happens in the country. Wouldn’t the officers involved be outliers?

For all that is wrong with the government and the criticism that is heaped on it, the fact is that it is the prime driver of development. Much of the good work it does is through invisible performers who rarely, if ever, get to take a curtain call.

But it is not as though their contribution goes unnoticed. Some time ago I had conducted a survey on Twitter. The question I asked was which of the following were carrying out their responsibilities in the best possible manner:

- Civil Service

- Judiciary

- Politicians

- Media

Of more than 3,000 participants, 65 percent voted in favour of the Civil Service, 22 percent for the Judiciary, nine percent for Politicians and five percent for the Media.

A similar survey was subsequently conducted on Twitter and LinkedIn to ascertain whether there was consistency in the findings. The question was tweaked a bit. I now asked, “With which of the following are you comparatively most satisfied or comparatively least dissatisfied in terms of carrying out the tasks expected of them?”

Of more than 1,500 respondents who participated in the Twitter poll (admittedly the sample size is a small one), the Civil Service was at the top (39 percent) yet again. It was closely followed by the Judiciary (34 percent). Politicians were way below at 15 percent and the Media lowest at 13 percent.

In the LinkedIn survey too, the Civil Servants led with 44 percent of the votes polled, followed by the Judiciary at 22 percent. The Media were marginally ahead of Politicians (17 percent) at 18 percent.

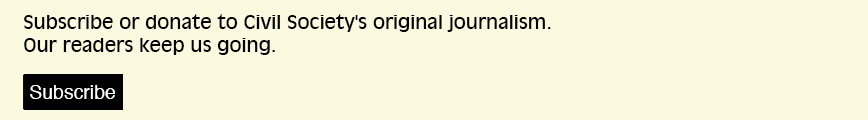

The mammoth Rewa solar project brought down the price of solar power

The mammoth Rewa solar project brought down the price of solar power

|

|

Manu Srivastava |

The gap between the Civil Servants and the Judiciary had narrowed considerably but the former continued to be at the top. Politicians and the media seem to have lost all credibility.

It is apparent that elite sections of society dislike (even hate) the civil service in general and the IAS in particular. By contrast, it is evident that ordinary people do not because they see their needs being addressed in the line of duty one day to the next. Here are some examples:

THE REWA PROJECT

When India committed itself to ambitious renewable energy targets before the comity of nations, many felt that it was punching far above its weight. Solar projects set up in India have mainly been on account of the creditable efforts of central public sector undertakings — the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) and the National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC). In setting up solar projects, the role of the states has been limited mainly to arranging for the land.

The same structure was conceptualized for the 750 MW solar project at Rewa in eastern Madhya Pradesh. Rewa Ultra Mega Solar Ltd (RUMSL) was set up as a 50:50 joint venture with SECI with a limited mandate to make land available.

The solar tariffs at that time were over `5 per unit. The Central government used to offer Viability Gap Funding (VGF) so that SECI and NTPC could procure solar energy and then, using the VGF, supply it to distribution companies (DISCOMs) of the states at `5 per unit. Bidding used to be on VGF, and the developer seeking the minimum VGF was awarded the project.

In this setting, Manu Srivastava, 1991-batch IAS officer, stepped in as Principal Secretary of the Renewable Energy Department in Madhya Pradesh. Part of his responsibility was to form and head RUMSL. He was not comfortable with the idea of a targeted tariff of `5 per unit, with VGF from the Centre, even though the solar park was to provide ‘plug and play’ facilities.

He convinced the central Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to let RUMSL handle the Rewa project independently, implying that the bid would be conducted by RUMSL and not by SECI as was the pattern throughout the country. The MNRE agreed but put a condition that VGF would not be made available to RUMSL. The implication was that RUMSL had to achieve a tariff of `5 per unit or below.

Srivastava realized that he needed strong and creditable allies. He soon explored possibilities with the World Bank, which was keen on the solar sector in India. The World Bank was looped in for concessional finance and IFC for transaction advisory services. RUMSL was the first agency in the solar sector to make such a move in collaboration with multilateral organizations.

One of the challenges was to locate customers. Distribution companies in Madhya Pradesh were not in a position to take the entire power generated. Hence, customers outside the state had to be located. The first breakthrough came in the form of the Delhi Metro getting convinced with the approach of RUMSL and developing sufficient foresight and confidence to sign into the project as one of the principal procurers of power, without any certainty of the tariff to be achieved, despite it being the first project of RUMSL.

As the project moved ahead, RUMSL gathered more allies — the Power Grid Corporation of India (PGCIL) for linking with the national grid, MPTransco for the development of internal transmission and Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) for developing an innovative payment security mechanism, as also Trilegal for legal services, PwC for managerial advice and Sgurr for engineering inputs. This broad team developed into Team Rewa.

The efforts of Team Rewa were justly rewarded. While the aim was to get a tariff of `4.50 per unit, the bidding went on incessantly for 36 hours and closed at an astonishing `2.97 per unit as the first-year tariff! This was lower than the cost of power from coal — the first solar project in India to have achieved this feat. More importantly, the project established the principle that low rates can be achieved without depending on subsidy by careful project structuring, robust project preparation and detailed contracting. It is the only project in the country to supply energy to an institutional customer — the Delhi Metro.

The project started injecting power into the national grid on July 6, 2018. This is the first solar project in India to inject directly into the national grid. The Rewa project got the World Bank President’s award. Rewa has been adopted as a case study at Harvard and at the Singapore Management University.

COVID IN MUMBAI

Mumbai has often been in the news for all the wrong reasons. When Covid-19 arrived in the country, Mumbai was not spared. In fact, the virus was relentless, creating havoc in the metropolis. It spread like wildfire during the last week of April 2020. The slums of Mumbai, especially Dharavi, Govandi and Deonar, were impacted. On account of limited testing facilities and short supply of beds in the city of Mumbai, there were a number of deaths. Some bodies were even found on the streets and road dividers.

One of the biggest slums of Asia, Dharavi, with a population of 800,000, was visibly out of control. There were only around 3,700 Covid-19 beds available in the city and approximately 1,500 people were reporting positive every day. Mumbai had become the hotspot of the country. There was panic all around and a sizeable number of residents of Mumbai were fleeing to safer places. Sheer helplessness provided ready fodder for the national media as well. All this resulted in tremendous pressure on the state government.

Iqbal Singh Chahal rose to the occasion in the fight against Covid-19 in Mumbai

It was in this set of circumstances that Iqbal Singh Chahal took over as municipal commissioner of Mumbai. On the very next day after taking charge on May 8, 2020, he walked into a Covid-19 ICU of a hospital to take stock of the ground reality. It was followed by a long walk in the containment zones of Dharavi to understand the actual situation prevailing in these slums. He was clear in his mind that there were only four pillars on which the foundation of the Covid-19 fight stood — disciplined and focussed testing, a large fleet of ambulances, an immediate increase in the number of Covid-19 hospital beds and substantial increase in the availability of trained para-medical and doctors in Mumbai.

The focus had to be on testing, tracing, tracking, quarantine and treatment. Between May 8 and August 1, 2020, a massive increase in health infrastructure was ensured under Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM). The number of Covid-19 beds was increased from 29,282 to 88,953. The total number of ICU beds was also increased from 480 to 1,755 during the same period. Similarly, there was a manifold increase in ventilator beds and ambulances.

Consequent to a myriad of efforts, recoveries went beyond 80 percent and the death rate that was initially eight percent in the month of April came down to almost half within a month and finally down to 1.8 percent.

MCGM rose to the occasion in the fight against Covid-19. Through well-planned, path-breaking and effective initiatives, the corporation, under the inspired leadership of Chahal, managed to take care of the crisis substantially in Mumbai.

WATERFALL BOUNTY

Madanpur Rampur is one of the 13 blocks of Kalahandi district in Odisha and is located 65 km from the district headquarters at Bhawanipatna. The block has a predominantly tribal population. It has many remote inaccessible areas and scattered habitation with sparse population in many villages. The lack of proper roads, bridges, mobile network and basic infrastructure, along with the presence of left-wing extremism, presents enormous challenges for implementation of various schemes and developmental plans. Many a time, the traditional beliefs of tribal people make it difficult to usher in change and implement new ideas. Consequently, the block has poor social, health and educational indicators. There is rampant migration to other districts.

During an interaction with block-level officers, the residents of Gandpadar village of Manikera gram panchayat raised the issue of water scarcity. The only possible solution suggested was sourcing water from some nearby perennial stream.

|

|

|

Rumana Jafri meets tribal women in her office in Kalahandi district (above); and the Mukhipata waterfall which became a tourist attraction |

Rumana Jafri, the Block Development Officer (BDO) at Rampur, together with the sarpanch of the Manikera panchayat and four others, set out to look for feasible solutions. After walking for more than five km through dense forest and on slippery trails, they came across a treasure, a waterfall that had remained hidden from the world for so long. It was at Mukhipata, close to Sulesuru village, but had remained unknown to the villagers and was apparently an unexplored area.

The water-related problem was solved through borewells. But in the waterfall Jafri visualized a whole new opportunity. The block administration decided to present the beauty of the Mukhipata waterfall before the world and develop it as a tourist spot.

A Mukhipata committee was constituted. The road leading to the waterfall was repaired. An entry fee per person and a parking fee were charged. Small shops selling water and essential food items were opened. Village locals were encouraged to sell tea and meals at subsidized rates to tourists. The spot was promoted through social media.

The results were immediately visible and within a short span of time Mukhipata started receiving a lot of visitors. These visitors in turn promoted it on social media. The shopkeepers earned a decent living and the entry fee collected was used to maintain cleanliness and to develop Mukhipata. In less than a month, the Mukhipata waterfall became one of the most visited places in Kalahandi district.

The dream of turning it into a tourist spot had been fulfilled. But the intention to strengthen livelihood activities around Mukhipata waterfall was yet to be realized. Hence, the idea of a rural haat near Mukhipata was conceived. This would be open every Saturday and Sunday as these two days witnessed the maximum number of visitors.

The focus of the rural haat was to generate livelihood activities, revive the dying indigenous arts and crafts of the area and promote forest products that were available in plenty in Madanpur Rampur block. The new mission to create a rural haat at Mukhipata took off. Villages like Jamguda, Jambahali, Dangapata for bamboo crafts, Mohangiri for Dhokra art and Madanpur for terracotta products were identified. A nodal officer was assigned for each such village. Individual artisans and women of self-help groups (SHGs) who produced crafts from wool, wood, paper and waste materials were also encouraged to sell their products at this haat.

Food stalls preparing local cuisine were given priority. Villagers and artisans were motivated to make products which they used to but had stopped making due to failure to find a market for them. The toughest part was to make the villagers believe that the products would sell this time round at the haat. This was done through multiple visits to the villages and interacting with them personally.

More than 500 families benefitted within a couple of months from the rural haat and many more are coming into the fold. Trainers were arranged to help the artisans reach new levels of innovation and efforts were made to cover other villages which were left out in the first phase of identification.

ECO-TOURISM MODEL

Vikas Kumar Ujjwal had taken over as the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), Lohardaga, in March 2017. While on tour, he was shocked and disturbed to see hundreds of poor villagers removing firewood illegally from a nearby forest. Ujjwal was told that as locals didn’t have anything else to do, they were taking timber to sell it in the local market to make a living. Two issues needed to be addressed: checking illicit felling and providing these people sustainable employment.

It was felt that all the effort would be insignificant and futile without a sustainable activity that could address both forest management and bringing about sizeable socio-economic impact.

The idea of Namodag eco-tourism emerged out of this necessity. This eco-tourism model was based on Joint Forest Management Committee (JFMC) members managing every activity from entry to exit of tourists. A nominal fee was charged from every tourist and in lieu of that, members of the Van Samiti provided facilities which included parking, cleaning, trekking, guides, sheds for sitting, and so on.

|

|

Vikas Kumar Ujjwal (centre, holding up a broomstick) introduced eco-tourism in Lohardaga |

Many shops and stalls have come up in the nearby area. The banning of plastic plates increased the demand for sal plates from the villages. Support from the district administration and engagement of local villagers ensured direct livelihood benefit to at least 25 people on a regular basis. There was increased patrolling by the forest department based on inputs from JFMC members to nab those still involved in the illegal timber trade. This compelled such people to shift to other activities.

Started in 2017, the registered count of tourists visiting has crossed 250,000 — generating enough resources for remuneration to those engaged and to build a corpus for infrastructure enhancement. On peak days the number of visitors reaches 10,000. The popularity of this place has generated enough buzz to attract tourists from nearby states and even other countries.

The new activity in this area has resulted in an 80 to 90 percent reduction in illicit felling due to rejuvenated JFMCs. Gradually, forest density has shown tremendous improvement. There have been signs of the return of wildlife such as sloth bears, deer, porcupines, foxes and avifauna. Better waste management has ensured responsible tourism. Increased reporting of offences by villagers has not only resulted in checking forest encroachment but also effective enforcement of forest laws. The Salgi JFMC was awarded as the best JFMC in the division in 2017-18 for its incredible work. An area that was once degraded has been regreened and is visible in satellite imagery.

MP TOURISM

The tourism scenario in Madhya Pradesh in the summer of 2004 was dismal. Despite its amazing bouquet of tourist destinations and cultural offerings it was nowhere in the front league of tourism in the country. The tourism corporation, mandated with the task of developing tourism, was in a state of despondency. Yet, a beginning had to be made.

Ashwani Lohani, an IRSME (Indian Railway Service of Mechanical Engineers) officer, took over as managing director of the Madhya Pradesh Tourism Development Corporation (MPTDC) in 2004. He started by cleaning up and improving upkeep at the corporation’s headquarters and then all other establishments and inculcating a sense of pride in the staff who became the real heroes of the revival effort.

The task was accomplished in three stints. The longest stint began in June 2006 with the agenda of shifting to the swanky Paryatan Bhawan that got almost completed during Lohani’s first tenure but remained unoccupied perhaps because it was too suave for a sarkari corporation.

|

|

Ashwani Lohani turned around tourism in Madhya Pradesh |

The first major issue was recovering outstanding food cost dues from a majority of unit managers including MPTDC’s flagship Hotel Palash. Waiving of undue and unjust recoveries led to a wave of enthusiasm in the corporation. Simultaneously, a drive for improving probity in public life by focusing on the eradication of corruption, drinking on duty and sexual harassment was also started.

A unique step was organising ‘Transparency Conferences’ that focused on corruption in the MPTDC in an open forum attended by all stakeholders. The first such conference, organized in Hotel Palash in Bhopal, had phenomenal impact and future conferences helped in maintaining the momentum. A line was clearly drawn.

Empowerment of officials was an exercise that was exhaustively carried out in Lohani’s first tenure. Powers were delegated extensively to field-level officials.

Next on the agenda was to create the world’s first broad gauge rail coach restaurant at Hotel Lake View Ashok in Bhopal — a dream project. A condemned second-class coach was purchased from the Nishatpura workshop in Bhopal and converted into a classy restaurant amidst an old-style railway station with its platform, magazine shop and a paan shop.

Christened Shan-e-Bhopal, this unique creation soon occupied pride of place in the city of lakes. The rail coach restaurant was conferred the National Tourism Award in 2008 in the category of ‘the most innovative tourism project of India’.

One major responsibility was branding of the state as a tourist destination. A new logo and the ‘Hindustan Ka Dil’ campaign on TV, radio and in the print media accorded tremendous visibility.

Lohani remained focused on rapid growth. New properties like the regional office at Indore, new hotels at Burhanpur, Dodi, Khajuraho and Mandsaur, new resorts at Pachmarhi, a new dhaba at Bhimbetka were all glowing examples of the new work culture at the MPTDC, a culture that stood for excellence in aesthetics, quality and service, while at the same time keeping a steady eye on operating ratios.

At Bargi, Delawadi, Halali, Kerwa and Tawa, the almost-dead irrigation rest houses were transformed into swanky resorts. Simultaneously, water sports were activated in a big way. While the lake in Bhopal was turned into the most popular entertainment spot of the city with power boats, water scooters and a cruise, prominent water bodies in way-off places were also given cruises, power and pedal boats, and entertainment centres. The setting up of Baaz, a centre for adventure sports on the outskirts of Bhopal, and a similar establishment at Pachmarhi gave a major push to adventure tourism.

CLEANING INDORE

Indore was known as an industrial town in Madhya Pradesh but shot into prominence after it was declared the cleanest city in the country in 2017. It has continued to be awarded and recognized as India’s cleanest city every year thereafter. What brought about a transformation that has continued to sustain for so many years?

Ashish Singh (below) transformed Indore into India's cleanest city

Ashish Singh (below) transformed Indore into India's cleanest city

It was not easy to start. A number of challenges were faced in setting up a system in the city. To overcome these challenges, Ashish Singh, a young municipal commissioner, and his team decided to transform the city through strategic planning and municipal waste management. Infrastructure needed to be strengthened.

It was not easy to start. A number of challenges were faced in setting up a system in the city. To overcome these challenges, Ashish Singh, a young municipal commissioner, and his team decided to transform the city through strategic planning and municipal waste management. Infrastructure needed to be strengthened.

Information, education and communication (IEC) were required to change public behaviour. The first step, therefore, was to create awareness amongst the people and the community through pamphlets, loudspeakers, rallies, meetings and public participation. People were made aware of the need to segregate wet and dry waste, its benefits and consequences on human health and environment.

Door-to-door collection and transportation services were designed in such a way that citizens got such services on all 365 days in a year irrespective of national holidays, festivals or Sundays. Accordingly, a ward-wise deployment plan of sanitation workers, drivers and utilization of vehicles was prepared.

For better segregation, three bins are used in each house. Door-to-door collection of waste is being done in all 85 wards of the city using partitioned vehicles. There are three separate collection compartments for wet, dry and domestic hazardous waste in each tipper. The wet waste from semi-bulk generators of 25 kg to 100 kg of waste is collected through the dedicated Bulk Collection System. The wet waste is transported by tippers to one of 10 transfer stations. At the garbage transfer station (GTS), the tippers unload the wet waste into dedicated compactors which compress and load the wet waste on hook loaders. The details of all the incoming waste collection vehicles are logged at the GTS.

Aadhaar-based biometric attendance of all workers is taken every day. All vehicles are monitored by a GPS-enabled tracking system. Any route deviation is penalized and multiple instances of deviation are ground for termination.

Sweeping of roads less than 18 metres wide is done manually by sanitation workers. Wider roads are cleaned by 10 ultra-modern mechanized road-sweeping machines. In all, 400 km of roads are mechanically swept between 10 pm and 6 am. Groups of workers are deployed to wash the city’s squares, footpaths and monuments with pressure jet machines.

The Indore Municipal Corporation (IMC) took over an existing under-performing Centralized Organic Waste Processing Unit. It completely overhauled the plant and repaired all machinery. The compost plant works to its full capacity of 600 metric tonnes of wet waste per day.

The IMC established decentralised aerobic pit composting units in 414 gardens to treat lawn cuttings, leaves and tree branches. It also took the initiative to produce and utilize bio CNG produced from processing of municipal solid waste.

Anil Swarup is a distinguished former IAS officer

Comments

-

Yeseko Dandia - June 2, 2023, 8:26 p.m.

Rumana Mam's remarkable work has established her as a role model for other officers, especially women, illustrating that with determination and resolve, a woman can bring about change regardless of the challenges faced. Her unwavering dedication is a beacon of hope to the nation, and her tireless efforts have opened up new avenues for progress, demonstrating that where there is a desire, there is always a path forward.

-

Sumita Chatterjee - June 1, 2023, 11:11 a.m.

I am so proud and happy to have read this article featuring Rumana 's commendable achievements in her area of work. Officers like her are the backbone of the state's administrative body. Rumana, I bless you to keep up the same level of dedication throughout your journey and may God give you the strength to do that. Your work ethics are a source of inspiration for the future officers.

-

Atish kumar - May 31, 2023, 12:38 p.m.

Officers like Rumana ji is boon for our society. Government and member from public should come in front to recognise their work and provide more complex problems of our society to them. So that greater good can be in system. I am upvoting for that noble purpose. Thank you Rumana Ji.