Goodbye to the Great Nicobar?

Civil Society News

THE Andaman and Nicobar Islands have always been known for their sparkling natural beauty. There are dense and sweeping forests, brilliant beaches and calm waters with hues unlike anything coastal elsewhere. The islands are also a treasure trove of living organisms, a collection of genes so ancient and pristine that they deserve to be preserved for their encoded mysteries.

Strung out on the eastern seaboard of India, the islands are located at a great distance from the mainland. Consequently, they have had a remote and shimmering presence of their own. Thus far, it has generally been agreed to avoid foisting infrastructure on them. Tourists do arrive and hotels have come up, but fortunately without too much impact. The islands have generally survived as gems of natural beauty and undocumented biological wealth.

It may no longer be so. A project is now underway for setting up a transshipment port, a township and an international airport on the Great Nicobar Island, the ecologically outstanding and southernmost of the islands.

The project has been whisked through clearances after it was conjured up by policy wonks in Delhi in the name of national security. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands make up a strategically placed archipelago. India is already well in control. A case has, however, been made out for a more elaborate presence.

To this end, `72,000 crore is to be spent over 30 years on the Great Nicobar which will rudely disturb the island’s precious ecology in irreversible ways. Its natural beauty and life-forms will most likely be lost forever.

Environmentalists compare the Great Nicobar with the Amazon — an invaluable asset to the planet in its quest for balance and continuity. Unique species abound. The leatherback turtle, for instance, arrives seasonally to nest, breed and disperse. There are ancient tribes with their cultures on the island.

In these times of global warming and climate change, preserving the Great Nicobar, and with it the other islands of the archipelago, should be a priority. Instead, about a million prehistoric trees, dating back to the Pleistocene era, are slated to be cut down. What transpires on the Great Nicobar will have a cascading effect on the rest of the islands as well.

It is not quite clear how a private commercial transshipment port and an international airport in Great Nicobar will serve defence interests. Far from the mainland and surrounded by existing ports in Sri Lanka, Singapore, Malaysia, Kerala, the port will struggle to become commercially viable. Building such infrastructure on an ecologically fragile island, prone to subsidence and earthquakes in the midst of an unpredictable and rising sea, may not be a smart investment.

The perceived security danger is seen from an expansionist China, which has spread itself out in the South China Sea. The Great Nicobar and other islands in the archipelago sit on the sea lanes that lead to the the Malacca Strait on which China is almost entirely dependent.

But China is far away from these islands and as yet it doesn’t appear to be in any position to grab them. On the contrary, now, with a port coming up and huge investments being made, geopolitical alarm bells will begin ringing. Chances are that China will see a danger to its interests.

The project has been framed in NITI Aayog, the Central government’s closed-door think-tank. Subsequent clearances have been given without proper oversight between 2019 and 2023. There has not been adequate or meaningful public consultation and debate. When matters have reached the courts, hearings have been peremptory and lacking in accommodation of complex environmental factors. National security blindly seems to have been the overriding consideration.

The Great Nicobar’s dense forests and pristine waters are a treasure trove of living organisms | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee

The Great Nicobar’s dense forests and pristine waters are a treasure trove of living organisms | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee

Would it have been enough to just strengthen the facilities that already exist on the Great Nicobar? Could a lighter touch have served India’s need for development and defence, and averted the damage that will almost certainly be caused by the planned moves?

There is an opinion in defence circles that India’s military presence could have been bolstered effectively without diminishing the environmental value of the islands or causing geopolitical stress points.

Admiral Arun Prakash was the Indian Navy chief and the Commander-in-Chief of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands Joint Command after Kargil happened. Now living in retirement in Goa, Admiral Prakash said to Civil Society that India’s presence on the islands is “not inadequate” but “needs to be reinforced”.

However, reinforcement, in his view, could happen without upending the ecology of the Great Nicobar and yet meeting defence needs.

“There is room to bolster, expand and reinforce the existing military presence and infrastructure. I would imagine that there is plenty of land and space available without significantly disturbing or disrupting any of the valuable ecological or anthropologic assets of the island,” says Admiral Prakash.

“The archipelago spans 700-800 miles north to south, but since most of the islands are uninhabited, it is up to us to bolster our presence so that our possession of the islands cannot be challenged,” he says, explaining that several smaller islands could have been used instead of the Great Nicobar.

| To read the accompanying interview with Admiral Arun Prakash to CLICK HERE |

All the heavy lifting for calling into question the planned build-up on the Great Nicobar has been done by environmentalists. Pankaj Sekhsaria, a professor at IIT Mumbai, has in his individual capacity played an important role in documenting the problems relating to the project and the damage that will be caused. He has drawn attention to the poor quality of environment impact assessment (EIA) studies and the lack of oversight.

|

|

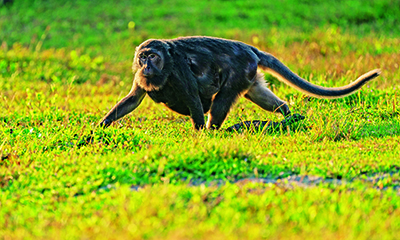

The Nicobar long-tailed macaque | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee |

Some of the measures to mitigate the effects of the project are laughable and bureaucratic in intent. For instance, ancient trees cut down in Great Nicobar are to be compensated for by growing trees in the Aravalis in Haryana at the other end of the country in the north! The former Haryana chief minister, Manohar Lal Khattar, talked of developing a night safari in the Aravalis. Imagine trading the uniqueness of the Great Nicobar for a night safari, say incredulous environmentalists.

Giant leatherback turtles arrive each year at Galathea Bay to nest. The beach of their choice was officially a sanctuary, but under the current development plans has lost this status. Instead, a 300-metre channel through the port is all that the turtles have for getting to their nesting site. It seems to have escaped official scrutiny that the turtles would be competing with giant ships to get to their traditional breeding ground in the bay which itself has been taken over.

A compilation of articles, The Great Nicobar Betrayal, curated by Sekhsaria, has recently been published to make available alternative points of view and awaken public attention, even as the government forges ahead.

The government’s project has been ironically named ‘Holistic Development of the Great Nicobar Island’. It is being implemented by the little-known Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation, which is based in Port Blair.

“Where is the scientific rigour and expertise?” asks Sekhsaria, pointing out flaws in the EIA for the project and the clearances given by the Union Environment Ministry.

“It is stunning that the environment ministry agreed to divert 130 sq km of primary forests on the condition that these forests would be compensated for by tree plantation in the state of Haryana, more than 2,000 km away,” he says.

|

| Megapde | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee |

“We are talking about a tropical evergreen forest spread over 130 sq km, a million old-growth trees, the northern Indian Ocean’s most important leatherback nesting site and an island that experienced one of the most severe earthquakes and tsunamis in human history in 2004,” he says.

Sekhsaria quotes from the EIA consultant’s site visit report which talks of the island’s dense vegetation. “The hills are steep, slippery and totally covered by multistoried vegetation. Whenever we could gain entry through some opening in the dense forest, visibility was poor and humidity was high…when one looks upwards to find what tree it is, it is not just one but many. Most trees are overgrown by heavy climbers and the tree trunks are covered by epiphytes including mosses, lichens, epiphytic ferns and orchids.”

The consultant’s report further adds: “It was impossible to use any measuring device like tape to make any quadrat in the forest vegetation. Hence intensive survey was carried out on both sides of Campbell-Indira Point for four days. It is about 45 km (sic) and the entire stretch was surveyed eight times in four days.”

That the environment ministry should have based its approvals on this kind of EIA report is stunning.

To be fair, the ministry laid down conditions for providing clearances. The only problem is, Sekhsaria points out, the conditions are bizarre.

For example, expressing concern over the project disturbing endemic owls, the ministry’s condition was: “Trees with nesting holes of owls to be identified and geo-tagged…. Such trees shall be safeguarded as far as possible.”

The condition is unimplementable. It would appear that no one in the ministry and its committees has applied their mind.

Says Sekhsaria: “Nesting holes of owls are tough to locate in the best of situations. We are talking of 130 sq km of pristine tropical forest. A million trees are to be cut. Even scores of India’s best birdwatchers working year round wouldn’t be able to survey a million trees.”

The Galathea river empties into the ocean at Galathea Bay, not far from Indira Point, the southernmost tip of India. Giant leatherback turtles have their nesting sites. Some go to Australia after breeding and others to Africa to return again as they have done for hundreds of years. It is, as a researcher described, an almost supernatural phenomenon.

To protect the turtles, the Galathea Bay Wildlife Sanctuary was created in 1997. The current project takes that protection away. Official permissions for the port have flowed in mysterious ways. Contradictions abound.

For instance, the sanctuary was denotified in January 2021 while the prefeasibility report was released in March 2021, two months later, by NITI Aayog’s consultants.

It is similarly interesting that the environment ministry released India’s National Marine Turtle Action Plan in February 2021 apparently without realizing that the Galathea Bay Sanctuary had been denotified a month earlier. Galathea Bay’s turtles find glowing mention in the plan when the very provisions for their protection had been removed.

Denotification was done by the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL). The Wildlife Institute of India (WII) ratified the decision without undertaking specialized studies, says Sekhsaria.

“The Wildlife Institute of India offered a mitigation plan but it was just a fig leaf. The leatherbacks enter the bay today through a mouth that is three kilometres wide. At least 90 percent of this access will be blocked, leaving the turtles just 300 metres for reaching the nesting beaches. The turtles will compete with huge ships, their sounds and lights and pollution,” says Sekhsaria.

The Great Nicobar is home to the Shompen and Nicobarese tribals. The Shompen, above, a shy people, have lived here in relative isolation, for centuries.

The Great Nicobar is home to the Shompen and Nicobarese tribals. The Shompen, above, a shy people, have lived here in relative isolation, for centuries.

Seismicity in the islands is also a reason for concern. The project site sits on a fault. Researchers have said there have been 400 earthquakes in 10 years. Janki Andharia of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) and her colleagues have been studying the islands after the 2004 tsunami and don’t think the seismic issue has been adequately addressed.

Sekhsaria says that the Great Nicobar’s coastline sank 4.5 metres after the tsunami. One visible proof of this is the lighthouse at Indira Point, which used to be above the water and is now in it.

“Investing in a port at precisely this location seems reckless,” says Sekhsaria. “Especially when rising seas are forcing island nations to relocate.”

The Great Nicobar has been inhabited by the Shompen and Nicobarese tribals for centuries. Both tribes have lived relatively isolated from the rest of the world. The tsunami of December 2004 slammed the island and killed one-third of the Nicobarese. The government relocated them into shanties. Both tribes yearn to return to their historical lands.

The Shompen, 245 in number in 2022, have been classified as a particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG). They rely on hunting and foraging in their forests. About 1,200 Nicobarese live in South Nicobar. Tribal chiefs have clearly said they don’t want to give up their ancestral land and forests.

This is their habitat, protected by the Forest Rights Act and a spate of numerous other laws. Yet the project was cleared under the Forest Conservation Act for diversion of forest land and two environmental clearances were given from the Union Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change in rapid succession in 2022.

Environmentalists invariably turn to the courts for a fair decision on their concerns. But there has been no legal relief — in strange circumstances.

There were four appeals before the eastern zone bench of the National Green Tribunal (NGT) which were summarily dismissed by a special bench, says Norma Alvares, a public-spirited lawyer.

Foliage and undergrowth are thick and difficult to walk through | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee

Foliage and undergrowth are thick and difficult to walk through | Picture / Dhritiman Mukherjee

The appeals were listed for filing of affidavits, as distinct from final hearing, on April 3, 2023. But a six-member special bench constituted for the day with judges and experts from the northern zone insisted on taking up the matter and disposed of it straightaway.

“The NGT proceeded to pronounce summary judgment on all four appeals, including the forest appeal, though not a word had been argued by one of the appellants,” says Alvares. “It passed its judgment, once again, in violation of the principles of natural justice.”

The articles curated by Sekhsaria are a sad testimony against a system controlled by forces that citizens can’t hold to account. It is reassuring that critics of the project are well-qualified and well-informed and ready to speak up for the farthest part of the country in the name of the environment. It is worrisome that an entire government and the system it controls should be unwilling to listen. That the Great Nicobar should be treated as dispensable is a tragedy of immeasurable proportions.

Comments

-

Sujata Patnaik - Sept. 28, 2024, 10:56 p.m.

This is why I oppose promoting tourism. I hate celebrating World Tourism Day. Certain places should be left untouched. So very sad. Pankaj, all your efforts gone down the drain.