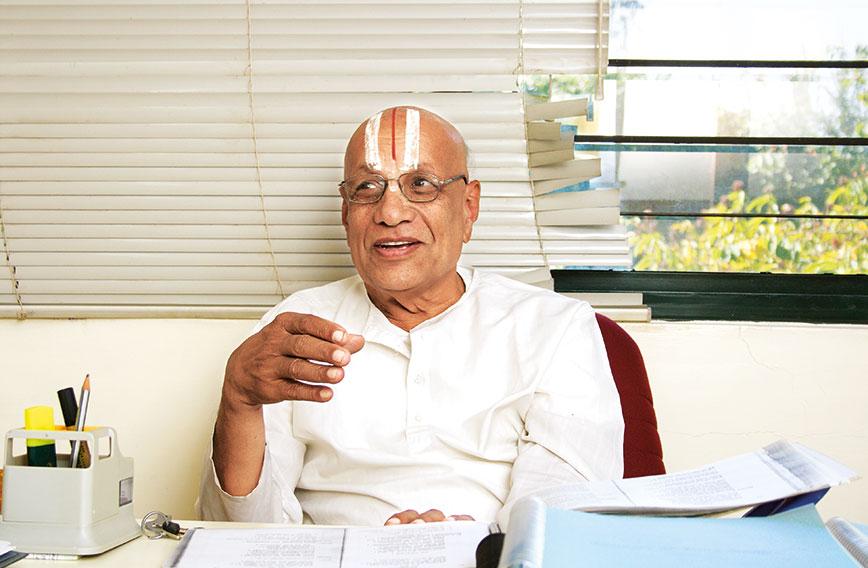

A Sanskrit scholar who catalogues and translates ancient medical manuscripts | Picture by Lakshman Anand

Future of healthcare: A roadmap for integration

Darshan Shankar

A former foreign minister of Singapore in search of a cure for his Parkinson’s disease admitted himself to the hospital at the Institute of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine (I-AIM) in Bengaluru. He had the typical Parkinson’s symptoms of tremors, imbalance and problems with gait.

Of course, he had access to the world’s best allopathic medical facilities. But he had turned to Ayurveda on the advice of friends when he had not found lasting relief in conventional treatment.

Two weeks later, he left Bengaluru significantly better. The tremors were less and his gait had improved. He also had an overall sense of wellbeing, which he had for a long time been missing.

What did the Ayurveda physicians do differently? Was it just the herbal medicines? Or was it Ayurveda’s holistic approach that had worked by treating the body as a complex whole instead of narrowly focusing on symptoms?

WATCH THE VIDEO: THE SURGEON IN AYURVEDA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yuG0Pt-TtcM&t=22s

In western medicine Parkinsonism is classified into two basic categories. Ayurveda, on the other hand, recognizes multiple sub-types, making it possible to treat each patient uniquely.

Ayurveda’s approach is guided by a sophisticated scheme of classification that can interpret specific patterns of symptoms. Simple algorithms are used to design variable treatments employing standardized herbal drugs. Clinical results from Ayurveda and yoga demonstrate much safer outcomes.

Ayurveda physicians have shown that through safe treatment and lifestyle changes they can slow down the progression of Parkinson’s disease. But they cannot cure it because it is a neuro-degenerative disease.

In allopathy, treatment of Parkinson’s relies on standard uniform medicines in increasing dosage. It is observed that when the treatment begins, the tremors reduce, but for further improvements higher dosages are administered and patients develop intense side-effects like involuntary movements.

Ayurveda, like other traditional systems of medicine, provides incremental but sustained results leading to a better quality of life. It is successful in dealing with non-communicable diseases — to Parkinson’s can be added arthritis, strokes, muscular-skeletal disorders, asthma and even non-surgical cancer conditions.

|

| A modern laboratory validates traditional Ayurveda drugs at I-AIM Picture by Lakshman Anand |

Progressive Ayurveda hospitals like the one at I-AIM have been playing a useful role in building bridges between western and traditional medicine. They visualize a future integrative health science combining the best theories and practices from different health knowledge systems.

In order to communicate outcomes of treatments, I-AIM documents patients under both systems. This approach makes it possible to see where they vary and how they can complement each other.

Ayurveda’s scheme of classification is more refined and makes it possible to distinguish between patients who are at different stages of a disease. Focused research can uncover objective biomarkers to demonstrate patient variability and thus refine management of a complex metabolic disease like Parkinson’s.

The time for integrative public healthcare is undoubtedly now. The National Health Policy (NHP) of 2017 takes a big step forward by emphasizing the need for combining different systems though much more needs to be done to translate this policy into legislation, regulation and operational programmes.

There is a democratic need in public interest to give formal status to integrative healthcare. It is already common health-seeking behaviour for people to use more than one system of medicine, depending on the nature of the ailment. For surgery, emergencies and acute conditions, the first choice is western biomedicine but for chronic and common ailments, for wellness and prevention citizens choose from traditional systems of healthcare that are available in different cultures. The current barrier to integration is not from citizens but from professionals who are determined to protect their own turfs.

A big scientific reason for an integrated approach is the limitations of both the traditional and western systems. One needs the other. Under the molecular approach of modern science not enough is understood about the patient as a whole and the fact that one patient could be different from another. Traditional systems, on the other hand, could do with greater molecular validation of their complex and apparently intuitive methods of diagnosis and understanding of the human body.

Since Independence, India has created one of the world’s largest structures for primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare. Even so, it is inadequate and far from universal in its reach. More than 70 percent of the population spends from its pocket on primary health and goes to a variety of practitioners. Second, there is a huge gap in the access and quality between rural and urban areas. Third, there is a rising incidence of non-communicable lifestyle diseases among the rich and poor alike for which conventional allopathic medicine does not have adequate answers.

It is in recognizing these realities, both scientific and social, that the NHP 2017 stipulates integrated healthcare. But before it can be implemented, legal and regulatory reforms are needed. The systems that govern medical education, research and services have to change.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK REFORM

India legally recognizes six systems of medicine — allopathy, Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, Swa-Rigpa, and homoeopathy with adjunct status to yoga and naturopathy. But in the absence of a unifying legal framework, the six systems function in silos with three different legal and regulatory bodies, two ministries at the centre and two different implementation machineries in the Union government and across states.

An Ayurveda clinic inside a government primary health centre in Delhi. Different systems are officially in use but lack the coordination that would make them more impactful. | Picture by Shrey Gupta

An Ayurveda clinic inside a government primary health centre in Delhi. Different systems are officially in use but lack the coordination that would make them more impactful. | Picture by Shrey Gupta

In Europe and the US, legally recognized health practitioners are encouraged to learn new medical skills from advancements in biomedicine or from any cultural source such as acupuncture, yoga and chiropractic services. With training and certification they are free to practise the new skill, on the strength of their original medical licence. Consumer laws ensure that the health practitioners are fully responsible and accountable and hence the new skills are applied with responsibility. It is necessary for Indian laws to move beyond narrow insecurity and at times public safety-inspired objections of cross-medical practice and in fact encourage health practitioners to learn new knowledge and skills and apply them with the fullest responsibility and accountability.

SYNERGY IS NEEDED

Two major medical councils regulate six recognized systems of healthcare with separate regulatory arrangements for each system and no mechanism for an interface across the councils.

How can integrative healthcare be achieved unless interfaces are developed between medical councils? A committee, appointed by the Union government and chaired by the late Prof Ranjit Roy Chaudhury, did initially recommend a single National Health Commission with sections for different systems of medicine. This recommendation was rejected.

Under the NHP 2017, the need today is for an Inter-Medical Systems Council, which can in phases usher in medical pluralism. NITI Aayog needs to take the initiative in making this happen.

MEDICAL EDUCATION

Integrative healthcare demands that bridges be built in medical education across different systems. How can this be done? The draft 2019 education policy by the Kasturirangan Committee has recommended that medical professionals redesign professional undergraduate and postgraduate medical education to include:

l Common foundational courses on medical pluralism at the undergraduate level for all the six streams of medical education.

l Core courses focused on specific systems (corresponding to the existing content of MBBS, BAMS and four other streams).

l Elective courses at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, which allow students to explore the bridging of systems.

This scheme can actually be implemented rightaway under the existing medical education system. All that it requires is a common foundation course and elective courses. The core programmes and medical degrees would, however, remain the same.

A dispensary for Ayurveda medicines

A dispensary for Ayurveda medicines

STATE-SPONSORED RESEARCH

India needs a national health research agenda. This agenda needs to be pursued by all medical streams. Outside the core agenda there ought to be scope for system-specific research priorities.

Today health research is conducted in silos. We have a Department for Health Research (DHR), the ICMR, and five research councils under the Ministry of AYUSH (Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy) All these entities have different research goals with no mechanism for synergy and collaborative ventures.

Can the mandate of DHR be so expanded as to cut across the medical systems and become the nodal point for developing a national health research agenda? This agenda could be implemented by different systems of medicine based on their strengths.

MEDICAL SERVICES

The current design, structure and functioning of medical services are antithetical to a pluralistic paradigm. Medical services even under the NHM, which has a very progressive integrative healthcare delivery mandate, are delivered in silos.

Allopathic services have a separate ministry, relatively large budget (1.4 percent of GDP) and administrative machinery at the centre and in the states and up to district and sub-district levels.

Similarly, AYUSH health services have an independent ministry, a minuscule budget (less than three percent of the allopathic outlay) and much smaller administrative machinery at the centre and in the states.

For political reasons today the two ministries can perhaps not be merged but at the administrative level, common objectives and a formal interface can be developed.

While the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in 2005 initiated a programme framework for integrated healthcare, it has not succeeded in achieving integration for reasons primarily related to an inappropriate implementation framework.

Can a new implementation framework for NHM be crafted which will bring about administrative, functional and structural coordination of health services across different systems of medicine at both the centre and in the states? Each medical system has its own needs of competent human resources, drugs, therapeutic infrastructure and so on. The NHM will need to fulfil the needs of each system. Integrative health services are therefore a complex task. It can be executed in phases with agreed short- , medium- and long-term goals.

The mainstreaming of integrative healthcare will certainly enhance quality of health services available to the public. The first step in this direction is to objectively identify through expert consultation the medical and public health conditions that can competently and independently be served by different systems of medicine. For example, AYUSH systems are reportedly strong in the management of non-communicable diseases. An assessment of strengths and limitations has to be done carefully by genuine experts.

In this scheme of integrative healthcare, “clinical documentation” should be mandatory and designed to be robust. One need not, however, attempt at the very outset to compare which system has the better ability. The relative strengths and limitations will automatically be generated by clinical outcome data analysis over a period of time. Citizens can be allowed to choose the system they would like to be served by. Human resources, drugs and infrastructure need to be adequately provided to each system for optimal performance. Over a period of time complementary modalities and a mature system of cross-referrals will develop.

Ayurvedic medicines have become over-the-counter formulations and are popular

Ayurvedic medicines have become over-the-counter formulations and are popular

The idea of integrative health services based on co-location and co-posting was already initiated in 2005. It has not delivered because of a poor implementation framework. The problem is that the management of mainstream health services rests with the modern medicine administration. The present NHM and mainstream healthcare system are managed by the Health and Family Welfare Ministry. Integrative practice in this system will remain flawed because the ministry has no provision to provide adequate budgetary and human resources, or infrastructure support to AYUSH systems.

The management design of a system that wants to deliver integrative health services needs to be radically transformed and implies a merger of the administrative machinery and financial outlays of two ministries so that it provides for optimal support to all participating systems. This redesign of a management system that provides a level playing field to all systems is a complex task. It can, however, be resolved in phases.

A strange anomaly exists in the field of surgery. Modern medicine has a huge shortage of surgeons in India. At the same time there are several thousand postgraduate Ayurvedic surgeons trained each year. But these Ayurvedic surgeons are ignored as a surgical recourse even though the curriculum for MS (Ayurveda) is almost 90 percent common to that for MS (Allopathy).

Ayurveda surgeons with a three-year master’s degree in surgery should in national interest be trained with the same rigour as allopathic surgeons. They should be deployed as surgeons in both the public and private sector. They should also be given the opportunity to specialize after their master’s degree in various branches of surgery like cardiology, ophthalmology and oncology. It is narrow, competitive politics and a huge waste of national human knowledge resources, to restrict Ayurveda surgeons to performing surgical practice limited to the anal region only.

The genesis of global surgery is Ayurveda and even as early as 1500 BCE caesarians were performed by Ayurveda surgeons. British archival records document that as late as the 18th century, plastic surgery techniques spread from India to the west. If only for the reason of repayment of the historical debt to Ayurveda, surgery in Ayurveda deserves to be strengthened and brought on a par with modern surgery.

The NHP 2017 has articulated a futuristic and progressive idea of creating wellness services in the primary healthcare centres of the country. The task of creating functional wellness modules for the health system should be entrusted to the AYUSH ministry. Dozens of reliable practices for prevention and wellness can be generated by AYUSH systems. The simple AYUSH solution of storing drinking water in copper vessels can completely eradicate microbial contamination in drinking water in India and prevent water-borne diseases, particularly in children. This preventive practice for safe drinking water should be widely promoted.

Modules in therapeutic diet and lifestyle advice for non-communicable diseases should also be entrusted to AYUSH systems. Integration of yoga into all the three tiers of health services can enhance the health security of citizens.

A FOURTH TIER

Health sector reform in India has the opportunity to innovate by creating a fourth tier in the health system. In India non-institutional healthcare is a centuries-old tradition. We have around 200 million informed households with knowledge of local ecosystem-specific food resources and herbal remedies. Local communities have incredible knowledge of hundreds of local fruits, vegetables and animal foods and over 6,500 species of medicinal plants.

A herbal garden

A herbal garden

Furthermore, every cluster of villages from the trans-Himalayas to Kanyakumari has community-based healers with special skills in areas like bone-setting, birthing, treatment of jaundice and dealing with poisons. There are believed to be about one million such healers and they could be better employed through formal recognition.

NHP 2017 advises documentation, validation, certification of prior knowledge of these healers especially in tribal areas. This indeed is a revolutionary recommendation and can result in the creation of a fourth non-institutionalized, low-cost and self-sustaining tier in the health system in which the providers will be homes and community-based traditional health workers. This tier will require a fraction of the investment that goes into institutional healthcare and can cover 40 to 50 percent of primary health centre needs.

INSURANCE

Today the insurance sector, while providing adequate and cashless coverage to allopathic services both in the government and private sector, provides nil or marginal coverage for integrative and indigenous systems. This is a lacuna that needs to be urgently removed to promote a national regime on medical pluralism as part of the health sector reform agenda.

Darshan Shankar is Vice Chancellor of the University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences and Technology and founder-trustee of the Foundation for Revitalisation of Local Health Traditions.

Comments

-

Amit Kumar Bose - July 15, 2020, 5:41 p.m.

Very informative