The Duas in their home office in Delhi

Cityscape tracking: Green maps show changes

Civil Society News, New Delhi

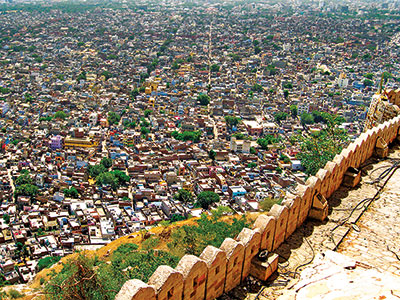

Cities are caught up in relentless change. For the better or not it isn’t always clear. But in a city, it is possible to be in the same place with everything being quite different. Over time, neighbourhoods vanish, highrises mushroom, roads and flyovers get built, rivers and waterbodies dry up, trees are chopped down and monuments decay.

While these changes are visible, mostly there is no validated record of how they came about or what has gone missing — such is the topsy-turvy style in which urban spaces have been evolving in India. But what if it were possible to plot the crazy paths that burgeoning cities take?

Could there, for instance, be a map which not only shows what currently exists but what was also once there? Is it possible to freeze-frame cities so that people know what they have and also learn from the past?

Such an effort has in fact been underway for some time. Green maps of Jaipur and Lucknow have recently been put into circulation. These are cities with much history, culture and natural resources. One is on the Gomti river and in the heart of the Gangetic plains, the other borders the desert in Rajasthan. They are geographically apart but equally caught up in cycles of change. Both are on a roll and expanding. Their populations appear to be growing. Developers are on the loose with housing projects. Municipalities struggle to cope with garbage and sewage. Water supply is a growing problem.

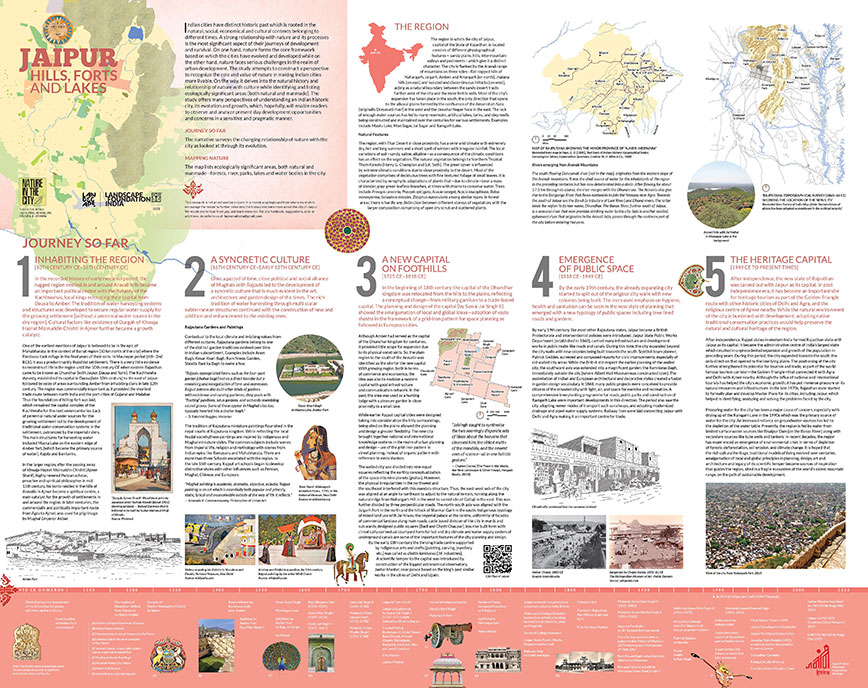

Nothing can put the brakes on Jaipur and Lucknow, but the green maps of the two cities provide an opportunity to pause and think. We can see in these simple but unique maps how Jaipur and Lucknow have come about over hundreds of years with ecological and locational challenges addressed over generations. The maps highlight important landmarks, heritage, greenery, traditional water systems and so on. These get juxtaposed with the teeming present and the challenges that rapid urbanization poses.

The Jaipur map

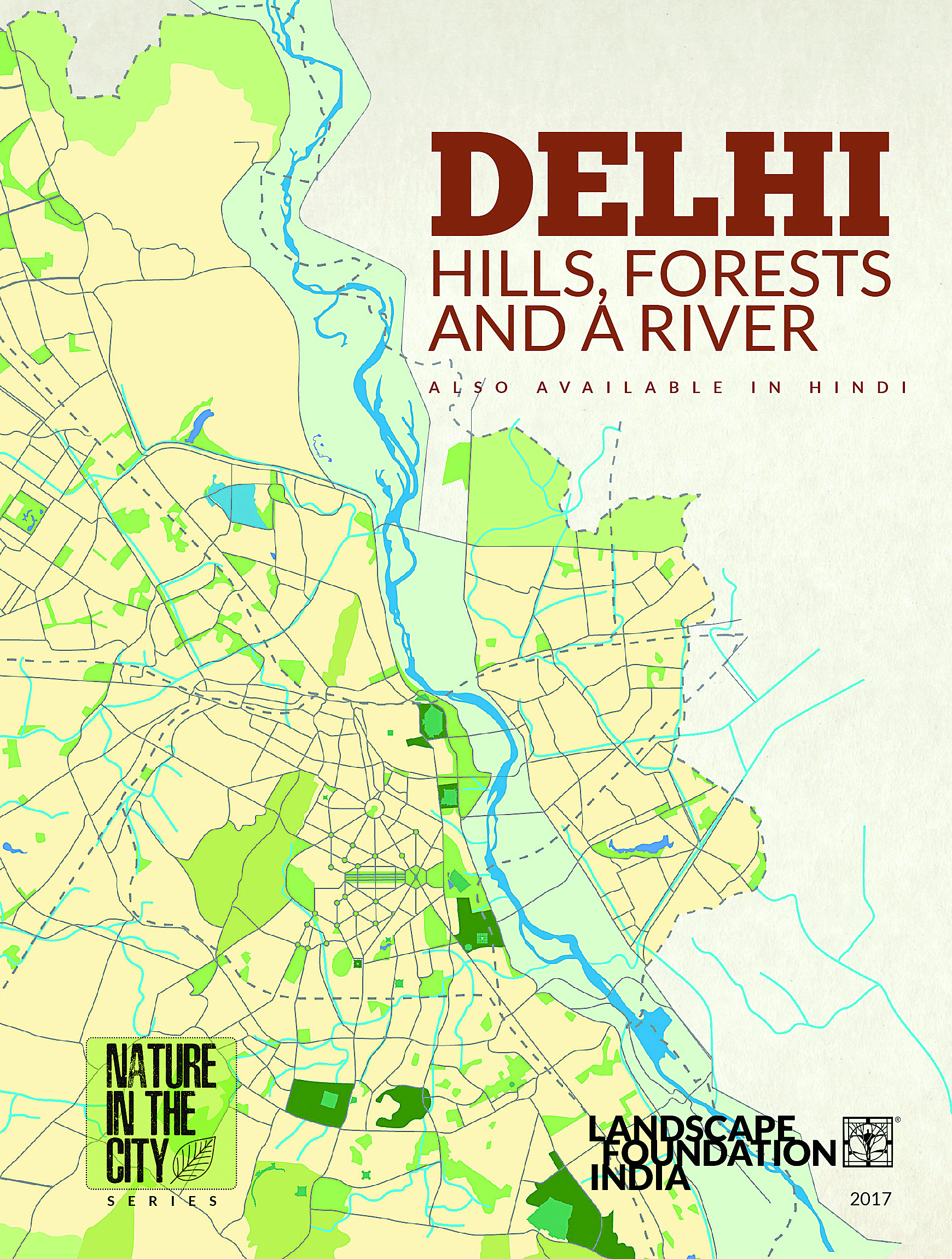

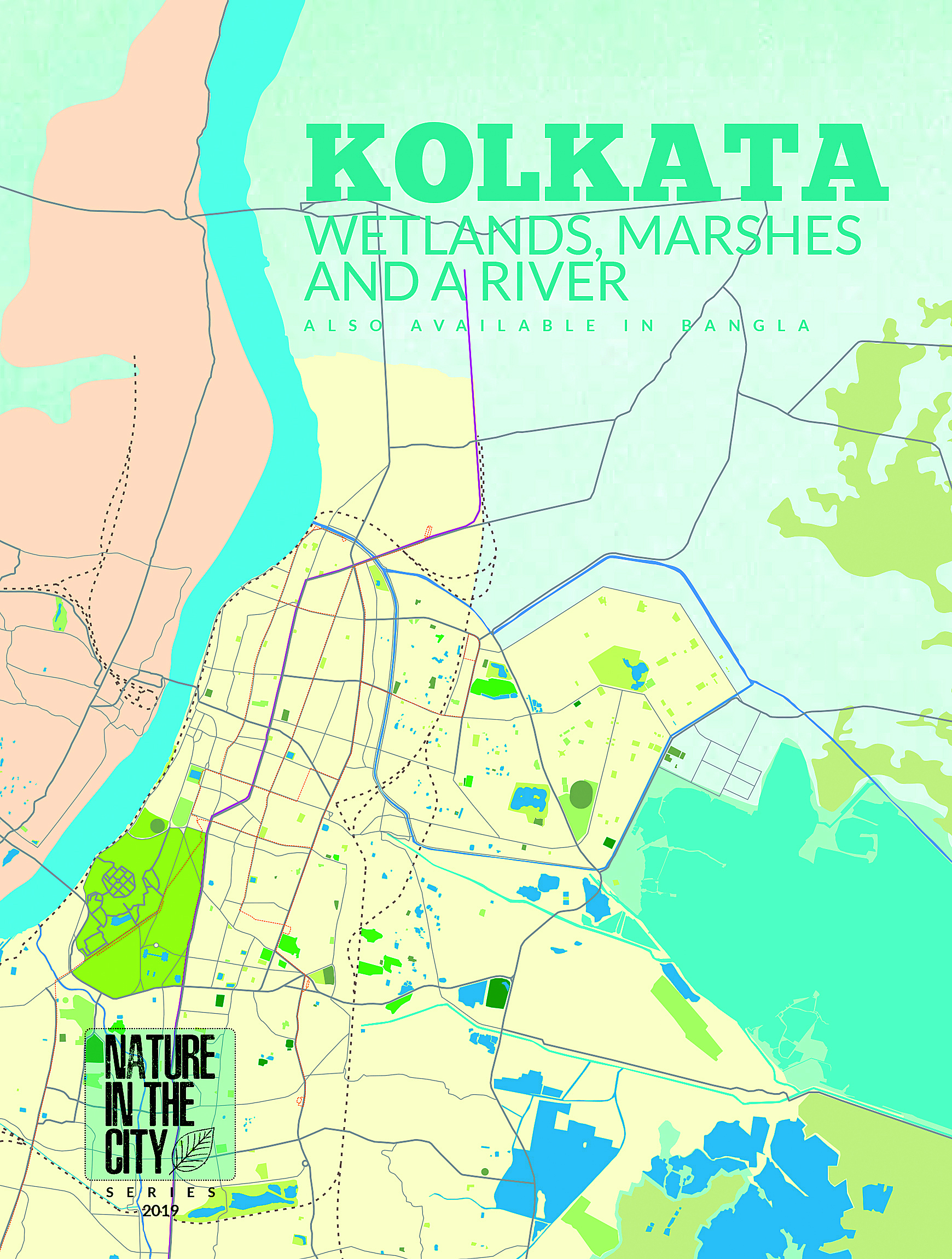

The Jaipur and Lucknow green maps are part of a series of such maps. Five other cities have been covered — Delhi, Pune, Bengaluru, Kolkata and Dehradun. The maps capture current realities, but while that is easy enough to document, their real value is in their tapping into history, community knowledge, environmental expertise, traditions and urban choices made over generations.

Behind this thoughtful initiative is a husband-and-wife team of landscape architects — Geeta Wahi Dua and Brijender Singh Dua who have dedicated themselves to a practice which espouses a balance between design and local ecology in the hope of making urban spaces sustainable.

Generally, landscape architects earn a living by prettying up the surroundings of a development. A five-star hotel would perhaps want to be bathed in greenery. An expensive private hospital might like an aura of serenity. Upmarket housing projects see value in extravagant invocations of nature. Landscape architects serving market needs are scene makers. They are makeup artists of a kind.

|

|

The teeming city of Jaipur as seen from the Nahargarh Fort and the serene Hawa Mahal |

It isn’t the way it was meant to be. Landscape architects have a serious role to play but seem to have yielded to the hurly-burly of the construction business. The Duas, however, seem to prefer to be professionals in their own style. Despite being well qualified and not short of commercial opportunities, especially since they are based in Delhi, they have instead channelized their skills, energy and resources into the Landscape Foundation India from where these maps have come. They also publish the LA Journal, a quarterly, which addresses issues of sustainability and balance about which they feel their profession should be concerned.

It has been all of 22 years and they continue to work from their small home office. Others might not see such dedication as being worth the time and effort. But the Duas in their pursuits seem to have an entrepreneurial spirit that puts them in a zone of their own.

Of what use are physical maps in the age of Google, one might ask. Entire cities can be closely scrutinized on desktops. Is a map on paper then the hallmark of luddites? But great ideas are often known first by their imperfections. The green maps, though seemingly outmoded in technological terms, have a contemporary value that satellite imagery and algorithms don’t provide.

The green maps go beyond the visible contours of urban spaces to bring them historically and culturally alive for people. They draw on narratives that emanate from the community. These are perspectives that might not otherwise have emerged. Cities are best understood from one street to the next. There are systems that served cities well but no longer exist. Uncovering multiple layers of urban life is the work of researchers who discover the stories that don’t get told.

The maps seek to create a sense of community ownership and belonging, and, emerging from that, perhaps a better future for cities. The maps also foster a spirit of enquiry. If people ask questions about the way they live, they could perhaps improve the quality of their lives and make their urban environment more meaningful. No city can be what it was before, but even as cities implode with people and services, looking back a little to learn from the successes and failures of the past can be beneficial.

“In 2017, we conceptualized the study of knowing our city, Delhi, from the point of view of learning about its urban history in the context of its relationship with natural resources,” say the Duas about how their first map came about.

“The idea was to emphasize the strong need to define cities and their histories in adequate environmental terms and place the urban built environment within the larger framework of the physical world,” Geeta explains.

“Along with deciphering the history part, we also tried to explore, identify and list significant natural and manmade landscape sites and places that play an important part in maintaining the city’s environmental and cultural health,” says Geeta, the more outgoing, who speaks for both of them in multiple interactions with Civil Society.

EVOLVING CITIES

To the Duas, such projects are useful for bringing “clarity and coherence to urban research”. Probing and recording the inception, growth and evolution of a city places its present-day realities in context.

Environment and conservation are key to the way the Duas think. Their studies, from which the maps come, seek to define an “environment-integrated historical perspective”. Doing so enables cities to better understand their current environmental problems and plan more efficiently for now and the future.

“Placing development strategies in context is especially valuable when the country is undergoing a fast pace of development on a large scale,” the Duas explain.

“Civilizations are about sequential narratives. Starting from the earliest settlement to the present, there is a temporal sequence, where there cannot be a present without a past or a future without both,” they point out. “Nature and culture are integrated in a single connected process.”

If this sounds a bit too arcane and up in the clouds, it isn’t that the Duas are mere theorists. On the contrary, the putting together of the maps has been really hard work that has required gathering information from an array of sources. In addition,there have been the hurdles of funding, printing and distributing the maps. The Duas are of course driven and have it in them to be long-distance runners. They keep going even when the odds seem too much.

Explaining how they began, Geeta says: “We adopted Delhi as our pilot project.While working on the project, a thought was also there to bring this work closer to the understanding and sensibilities of larger society, common citizens and the young generation of students from regular colleges and not only for professional circles. There was a strong urge to reach out to other groups.”

The outcome of the Delhi project was the first map, double-sided and easy to refer to. It was in two sections — Journey So Far and Mapping Nature. There were two versions, in Hindi and English.

The outcome of the Delhi project was the first map, double-sided and easy to refer to. It was in two sections — Journey So Far and Mapping Nature. There were two versions, in Hindi and English.

“The environmental knowledge about cities is not divorced from their economic, social and political milieu. They are densely interlinked and intrinsic to the holistic perspective. Various data sources, based on multiple disciplines, have helped us to form a meaningful and enlightening perspective towards understanding these cities,” says Geeta.

The Duas have referred to academic books, archival records, archival paintings and maps, gazettes and reports, literature and films, stories in print and on the web.

“For the mapping section, we have referred to Google Earth and Google Open Street maps to create the main frame, which gets further informed by latest tourist maps, municipal maps and other relevant information available in the public domain,” they say.

The process of arriving at a narrative has been one of consultation with experts in different fields who belong to these cities. They have talked to historians, ecologists, writers and authors, social scientists and design professionals. A crucial part of the study has been site visits to validate information.

For the Duas the role of the landscape architect is to “provide stewardship” combining natural resources with design and planning. It is also to recognize and syncretize different perspectives because India is a multicultural and geographically diverse country with a rich cultural past.

THOSE AHA! MOMENTS

“For us it is the most fascinating and at the same time challenging spatial design discipline. Reinforcing ideas of maintaining natural and cultural continuities, celebrating diversity, adopting a multidisciplinary approach while working on different scales, has been our philosophy,” the Duas say about what inspires them.

With this orientation, putting together the maps has been rewarding, a journey of discovery. In Delhi, what was once a stream of the Yamuna along the Red Fort is now the metalled Ring Road. The Yamuna itself was a fast flowing river and never regarded as the main source of water. It was only under Feroze Shah Tughlak in the 14th century, when the Western Yamuna Canal was built, that the river flowed to pastoral landscapes around settlements.

When settlements shifted from the southern side to the east along the Yamuna, Delhi’s network of baolis, tanks and channels deteriorated because they were no longer so important.

“The river played an important role in the siting of settlements like the Purana Qila, the shrine of Hazrat Nizamuddin Aulia, Humayun’s Tomb, the Red Fort, Feroz Shah Kotla, to name a few. But except for the glimpses in history, archival paintings, photographs and maps, there is no tangible physical evidence on the ground. That relationship is lost forever!” says Geeta.

KOLKATA'S WETLANDS

Kolkata was India’s first modern city, which may be difficult to imagine given its current state. It had a brilliant canal network and an intricate water transport system. Channels, streams and rivers were connected. It was India’s first modern city with underground drainage, piped water supply, garbage disposal, transportation networks and a grid pattern of development.

Kolkata was India’s first modern city, which may be difficult to imagine given its current state. It had a brilliant canal network and an intricate water transport system. Channels, streams and rivers were connected. It was India’s first modern city with underground drainage, piped water supply, garbage disposal, transportation networks and a grid pattern of development.

In Kolkata’s Botanical Gardens in the late 18th century were laid the foundations of plant taxonomy. And spread over an area of 12,500 hectares, the East Kolkata Wetlands were and remain a natural waste recycling zone, taking sewage from the city, cleansing it by keeping it standing in ponds and growing fish in the nutrients-rich water before it flows into the river. East Kolkata ranks as the world’s largest wastewater-fed aqua culture system.

Jaipur, because of its proximity to the desert, devised traditional water harvesting systems for its survival. Tanks, lakes and baolis were part of an evolved water management system which remains relevant today even though with neglect such structures have gone into disuse.

Conceptualized as a Rajput capital, Jaipur was the new capital after the shift from Amber to the plains. It combined principles of Vaastu shastra and the grid iron pattern of street planning taken from Europeans.

|

|

Hussainabad ka talaab and the |

In Lucknow it is the Gomti which played an important role in the city’s development, underlining the need to keep the diminishing river healthy today. The city was known for its confluence of cultures and traditions. It was also known for its gardens and orchards — some 22,000 hectares were recorded as being under orchards. There are pointers for present-day Lucknow in these details.

These and other moments of discovery abound in the maps as they juxtapose past and present in the search for effective urban solutions. The message being that there is much to take from the urbanization efforts of the past.

The maps have been funded from various sources. The Delhi one was crowd-funded. Research grants and donations from philanthropies have seen them through. As may well be expected, post-Covid funders have been difficult to find. The Jaipur and Lucknow maps were funded by the Duas themselves.

Their circulation has been limited as is only to be expected from a small initiative with a paucity of resources. In purpose and spirit and the intricate connections they make, they are, however, a valuable contribution to rethinking Indian cities.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!