Ram Gidoomal’s exciting story of expulsion, prosperity and caring

An outsider in politics

Ram Gidoomal

|

WHAT on earth was I doing here? Winter sun streamed in through the windows of Toynbee Hall’s meeting room. I stole a glance along the platform at my competitors. We had been seated in order of our parties’ importance. On my left sat people like Frank Dobson, Stephen Norris, Glenda Jackson and Ken Livingstone, all big heavyweight names with their heads held high. And then there was me. The fifteenth candidate. The last in line.

In front of us, the oak panelled room was packed with interested spectators, journalists ready with their questions, and photographers homing in on the other, more famous, candidates. How did I end up at these hustings? It certainly wasn’t my idea. Politics was one game I had never intended to play. Yes, my public appointments had begun to bring me into contact with politicians — something I always found interesting — but it wasn’t a sphere in which I saw myself working.

My contribution to the Better Regulation Task Force involved advising on policy making and was an amazing experience — like being a minister without being a minister. You had all the influence without being elected. This was how I liked it. I was happy to give business input, but to be a politician? No, thank you. I simply didn’t need it.

Being at the heart of government for the Task Force already brought me the kind of opportunities I’d only dreamt of previously: newspaper articles, Radio 4 interviews, television. There were meetings at 11 Downing Street, the Old Admiralty Building, and the Cabinet Office at 70 Whitehall, not to mention dinner at the banqueting hall.

Then, when Peter Mandelson asked me to serve on the Department of Trade and Industry’s National Competitiveness Advisory Committee, I even found myself invited to a breakfast meeting at 10 Downing Street.

Walking into a magnificent dining room with about 20 others, I found my place at the table, nodding to my companions — all well-known business leaders. I held back a gasp as I studied my personalized seating plan and realised I would be sipping tea and munching bacon and eggs just a couple of seats away from Tony Blair. It meant that I was able to speak up for small businesses, complaining about how they were treated by the larger companies, many of whom were represented at the breakfast. Later that day, two Permanent Secretaries I knew called me to say they’d seen my name in Dispatches. I’d managed to make my voice heard.

But it was after another television interview that I met someone who would set me on a new course. I had been interviewed for a BBC South Asia report and was just leaving White City TV studios when I felt a hand on my shoulder.

“Ram, great interview! I’ve just seen it.” David Campanale caught up with me. “By the way, have you heard about this mayoral race? They’re looking for candidates.”

“Oh, interesting,” I smiled at him. “I’ll mull it over and send you some ideas.”

Later, true to my word, I sent him a list of half a dozen names, a mixture of people who were speaking up against violence and injustice, plus some business leaders. Blair had made it clear he was interested in people like these. Having sent David the list, I felt I had done my bit and thought no more of it, until a couple of weeks later when he called me up.

“Thanks for the suggestions, Ram. Good to have a list of names, but, er…we’ve been discussing this as a committee and we think you would be an ideal candidate.”

I was momentarily speechless. It was flattering to be suggested, of course — especially as I knew this was a group of young people, millennials who were concerned about their city, and needed a spokesperson. I shouldn’t have been surprised: it was youth-led. It was always young people, with their fresh take on issues, their keen eyes seeing right through inequality and discrimination. Young people who had not yet been ground down by the ‘cannots’ of this world, instead able to see the genuine needs and the possibility to act on them. Once again, they were showing me my own mandate: Don’t let what you cannot do stop you from doing what you can.

But a mayoral race? That was the last thing on my mind. All the career advice I had ever had back during my Kenyan teens guided me towards worthy professions such as medicine or law, possibly business. But not politics. Never politics.

Partly to buy some time and partly to avoid being immediately negative, I told him I would go home and talk to Sunita about it. I was pretty convinced she would agree with me and then I could just go back to David and say, “So sorry, the wife says no.”

But she didn’t say no. What she said was, “Well, don’t we usually pray about these things?”

I sighed. “Okay, then.” What I was actually thinking was, “You pray your way and I’ll pray God says no.” So we prayed and we waited. There was no lightning bolt, no immediate certainty either way, but over the following weeks, the more I looked around London, the more I saw injustice. Around the same time, I was at a business board meeting for the Training Enterprise Council and a consultant we had engaged showed a map of London from 100 years ago, comparing it with a current one. Both maps were colour-coded to show areas of wealth and poverty. There were a hundred years between the two maps, and those colour-coded areas had not changed. To satisfy my disbelief, I delved into the statistics. It was true. Even then, in the year 1999, a baby born in Hackney had six years less life expectancy than a baby born in Westminster.

London is my city. I came here as a refugee and, despite some hard times initially, it has been amazing to me. But this map, these statistics, I couldn’t believe this was the same city. What could I do to help change this?

Of course, I hoped I was already making a difference through my many public appointments. I was speaking up for the underprivileged and the disadvantaged. The Better Regulation Task Force, where I served as a small business representative, was chaired by Lord Haskins and was overseen by the Cabinet Office, and through this I was made chairman of the Anti-Discrimination Legislation subgroup, a UK-wide initiative. Labour had just come to power, and I found myself regularly called upon by Downing Street advisors. Many of the ministers were just cutting their teeth in their new roles. However, because of the number of ministers in charge of different kinds of discrimination, my work was becoming a challenge. Lord Haskins stepped in and said, “Don’t worry, we’ll talk to Jack Cunningham.”

Rumour had it that Jack Cunningham was the one who wore size 12 boots. He was Tony Blair’s cabinet enforcer. With him on our side, the task became much more straightforward. He gathered any minister with anything to do with discrimination under one roof for me, giving me the opportunity to share ideas and consult with them and their advisors all at once on this crucial topic.

I certainly didn’t feel compelled to take on another challenge just yet. But, as time went on, it occurred to me that maybe there was something more I could do. Maybe I could make more of a difference to the inequality in my city. The Biblical values upon which the country had been founded were being side-lined and while I, more than anyone, understood we lived in a multi-cultural society, the core principles themselves had served us well and were being undermined for no good reason.

Perhaps what really qualified me was that my burning desire for truth was always stronger than my need to stay safely quiet on issues. On seeing discrimination or injustice, I have to speak up. For example, during a meeting at the Old Admiralty Building for the Competitiveness Advisory Panel, I was shocked when the chairman of a successful company commented, “We’ve got to watch these shady Asian countries and shady Asian businessmen. They behave in ways that are not quite ethical and then we have problems competing.”

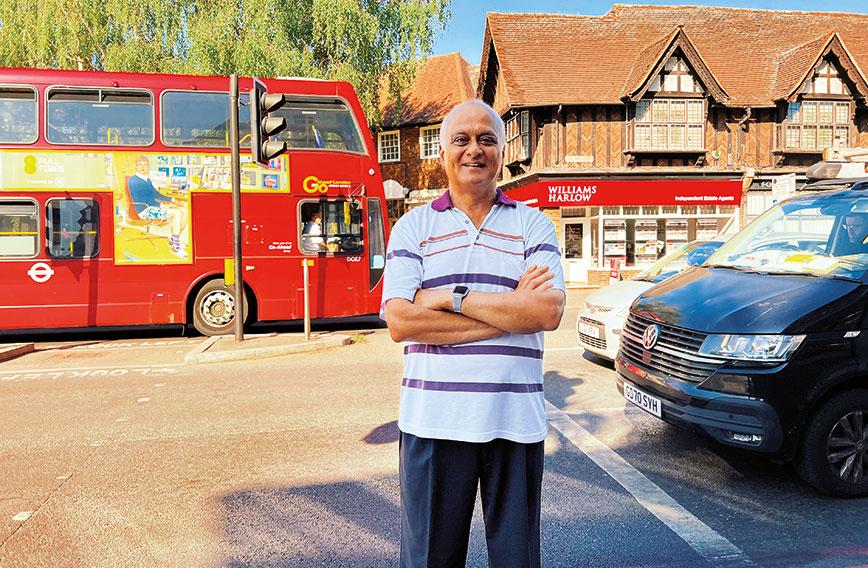

The alternative voice: Ram Gidoomal in front of one of his billboards during the election for mayor

The alternative voice: Ram Gidoomal in front of one of his billboards during the election for mayor

I looked around the room at the press, political leaders, well-known chief executives, waiting for someone to condemn this statement. A large majority of those present had recently signed a public document confirming they would speak up against racism but now there was silence. Eventually, I put my hand up.

“May I please remind the gentleman on my right that he’s forgetting what took place in our very own Parliament where we had cash in brown paper bags exchanging hands between MPs so that questions would be asked in Parliament. Is that ethical or unethical? Please, let us be careful before we point fingers at these countries and communities.”

Again, deadly silence. I moved on, knowing at least that I had spoken up, but a few weeks later I happened to meet a Downing Street transcriber at a Bank of England lunch. Recognising my voice from the meeting’s recording, he praised me for speaking up, having felt horrified at the racism he’d heard. A couple of weeks after that, I received a call from Robert Peston, wanting to include this story in the Financial Times. Sadly, it was blocked. It was impossible to get the transcript from Downing Street, which would have served as the necessary evidence.

I still had no interest in becoming Mayor of London, but I began to feel convinced I could contribute positively to the London Assembly. However, in order to gain one of the 25 seats there, a goal I had assessed as achievable, you had to have profile. You had to have some traction. You had to run for Mayor.

So I joined the Christian Peoples Alliance and was elected leader. We created a manifesto around their six principles of Social Justice, Respect for Life, Reconciliation, Active Compassion, Stewardship of Resources and Empowerment. The point was that although these are indeed Christian principles, the genuine life-enhancing goodness they aim to achieve is universally recognised. They are based on giving fair opportunities to all, and on narrowing the rich-poor divide. Although these six principles are solidly Biblical, they are also honoured by men and women of goodwill everywhere. In short, you don’t have to be Christian to support Christian principles. For me, having ‘Christian’ in the party name was not a sign that we were against other faiths, but a guarantee that we ourselves would respect them. In fact, much of my support did not come from Christians at all but from other minority groups.

Even while I was still deciding whether to proceed, we were totting up the costs: £10,000 to register, another £10,000 for your name to appear in the booklet, then money for a team, office, and staff. That’s a tall order. It was looking like £100,000 just to wash your face and say, “I’m running.”

However, I knew that, with the contest for an Assembly seat calculated on proportional representation, if I even got 4% of the vote, I would have a seat. I looked at the Christian population of London and I looked at all the other contacts backing me and thought, “Why not try?”

The support I received from the Asian community was huge encouragement. One of Sunita’s

|

| Finally a chance to make his pitch on the BBC Radio 4 Today |

cousins was quick to get out his cheque book and pay the £10,000 registration fee, then funds began arriving from others to meet the remaining costs. Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims, Jews, and agnostics put their hands in their pockets to support me financially, as well as rallying all their friends and staff to vote for me.

The BBC refused to give us a political broadcast. I went to plead with the director herself, asking, “Where’s democracy? We’ve paid our £10,000 but we’re not getting an equal say.” It’s impossible to visit every home in London, but these other parties would appear in everyone’s living room on TV. However, she would not budge. I left the meeting in tears. What chance did I have?

The Times, however, found me a little more appealing. Breaking the embargo on the press release, they jumped in with the headline, “Former refugee throws his hat in the ring.”

That did the job! Refugees began to believe this was their city too, and when it came to that first hustings at Toynbee Hall, it seemed that half the immigrant population of London had turned out for it.

I looked down the row of accomplished political faces once more, reminding myself exactly why I was among them. As the meeting got underway, the speaker turned to the line of candidates and asked us,

“What would you do for London?”

Three minutes. That’s how long each of us had to put forward our case. As I listened to the slick long-timers talking suavely about transport, housing and crime I began to panic. At the end of each three-minute spiel, the house filled with applause. If there had been a clapometer, they’d have been up there with six, seven or eight out of ten. I breathed deeply. What should I say? I thought about what Jesus would do. Why are you running? I asked myself. You came as a refugee, you know the refugee world well. You’ve got to speak up for the disadvantaged.

So I did. I spoke for three minutes and said, “If I’m elected, I will work for the homeless, the jobless, and the carless.”

The place erupted in cheers and applause, the Richter scale going up to 12, 13, 14 out of ten. The other candidates stared in astonishment as if seeing me for the first time and wondering, “Who is this man? Who is this upstart who’s just made the place explode?”

I went home, feeling a lot better. Just as we were about to go to bed, BBC Radio London news came on.

“Let’s have a quick listen,” I said to Sunita.

The interviewer was talking to the favourite candidate about his manifesto.

“What do you see as the three biggest issues for London?” “Well,” he began confidently, “I would say the homeless, the jobless, and the carless.”

|

| Gidoomal with Nelson Mandela |

We looked at each other and burst into surprised laughter. “How wonderful,” I thought. “If, in one meeting, I have switched the agenda of the London election so that everyone’s focusing on the homeless, jobless, and carless, then my work here is done. I don’t have to be Mayor of London. They can do it for me.”

At the time, Dame Rennie Fritchie (now Baroness Fritchie) was the Chief of the Independent Public Appointments Office. She made a point of commenting to me, “Ram, I loved your intervention at the debate, I thought it was very good.” Simon Jenkins also quoted it in his piece in The Evening Standard, adding “The Conservatives should beg Gidoomal to join them!”

So, although I struggled to get backing from some people, others exceeded all my expectations. For example, Lady Susie Sainsbury and Viscountess Gill Brentford wrote a joint letter to The Telegraph publicly affirming and recommending me. This was in addition to one that Prue Leith had written to The Evening Standard. Once again, I felt the tremendous power of female support and was moved that they would make such efforts for me.

Meanwhile, another tremendous boost was coming. The New Statesman ran a blind web-poll called Fantasymayor.com. They put up six manifestos: Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrats, Greens, Ken Livingstone (running independently), and mine. When people were initially asked to vote by their party preference, I didn’t do very well. Around 56% said Ken Livingstone. A mere 3.5% went for me.

Next, however, voters had to answer 15 policy questions asking what they wanted from their mayor on a range of issues. This time they voted ‘blind’, purely on the policies, without knowing whose they were. The website then matched their aspirations with the policies of the candidates. The results were incredible. I came out top and beat Ken Livingstone by a substantial majority.

The voters were no doubt surprised to see who they had voted for. Many would not have wanted to be associated with the word ‘Christian’. But these were not ‘Christian values’ in some impersonal, abstract sense. These were ‘people values’ because Jesus came to live among people and to help them. As the art historian Hans Rookmaaker said, “Christ did not come to make us truly Christian but to make us truly human.”

Unsurprisingly, the Fantasy Mayor story caused quite a stir and was even picked up by Time magazine in the States. Every national paper here also admitted, “If this election were on policies alone, Gidoomal would win by a landslide.”

But alas, elections are not won simply on policies but on personalities and profile. I knew that. Still, it was a huge affirmation to find I was so in tune with the people of London. The fact that my policies were the most closely matched to the aspirations of Londoners was a profound statement. More importantly, it spoke volumes about what people really wanted. Everything in my manifesto had Biblical values at its roots. For me, the only obvious conclusion to draw was that people wanted and needed such Biblical values, but just didn’t know it.

When the actual election came around on 4th May, of course, I didn’t win. It had never been my main goal or expectation. Unsurprisingly, Ken Livingstone stole that particular show. I did, however, save my deposit, because even with no track record and very little media coverage, we managed to gain nearly 100,000 first and second preference votes, coming fourth out of the political parties. Much as I love the Green Party, I was incredulous and rather proud to learn that I had come out higher than them, despite their 25 years of history.

Although I thought that my 4% of the vote was fairly meagre, I was surprised by the number of people who got in touch to congratulate me, assuring me that in political circles, that’s quite an achievement. Suddenly I realised everyone was talking about me, in the House of Commons, the House of Lords…everywhere was the murmur of “Who is this man?”

Even if my result was no landslide, I had theoretically secured enough votes to win the 25th seat, under the D’Hondt Rule.

When I wrote my book, How would Jesus Vote? with David Porter in 2001, I made the following point: “If in your local constituency, a Muslim has the policies that fit your aspirations the best then I would say vote for the Muslim.” Christians are sometimes shocked by this, but we cannot just vote for a Christian candidate simply because the label is right. The policy and content must be genuinely in line with what we believe to be best for our community. In the political sphere we can work together with others for the common good, respecting other people’s freedom either to practice their own religion or to be atheist.

The same point was made in a rather more comical way during the book’s launch, when Nicky Campbell interviewed me on BBC Radio 5 Live. Someone called in and said, “So Mr Gidoomal, this book is about how Jesus would vote?”

“Yes…”

“Well, didn’t Jesus walk on the water? So that makes him a ‘floating voter’, doesn’t it?” “Exactly!” I laughed.

That was the point of the book. Be floating voters. Don’t let your vote be taken for granted by any party. Check them out, scrutinize them. See what difference they will make on a national level. Then cast your precious vote.

Another caller commented that my six principles would not come cheap. “True,” I replied.“But what is the cost of not doing them?”

To take one example, I wanted to improve access to work for those with disabilities. The cost of those people not being able to work was much greater, both for them personally and for the wider community, than the cost of enabling them.

I appreciated this chance to have a voice. Of course, there would always be some people who wanted to look for the negatives. The day after the first election, the media were quick to contact me.

“So, Mr Gidoomal, you didn’t win.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “And 11 others didn’t either.”

I didn’t win, yet I knew that I had managed to get my points and ideas across. I didn’t win but I knew I had pushed some worthy issues higher up the political agenda. I didn’t win but the idea in my manifesto for creating a Boost Bond for East London (inspired by Michael Schluter who first set up such a bond in Sheffield) became a reality and has now issued £1 billion of bonds for social impact across the UK. I didn’t win, but I didn’t need to. Good things still came out of the time, energy and money that had been invested.

As before, when I had had the impact of a minister without actually being a minister, I realised that sometimes the secret of changing the world is to have influence without power. It’s the art of letting other people have your way.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!