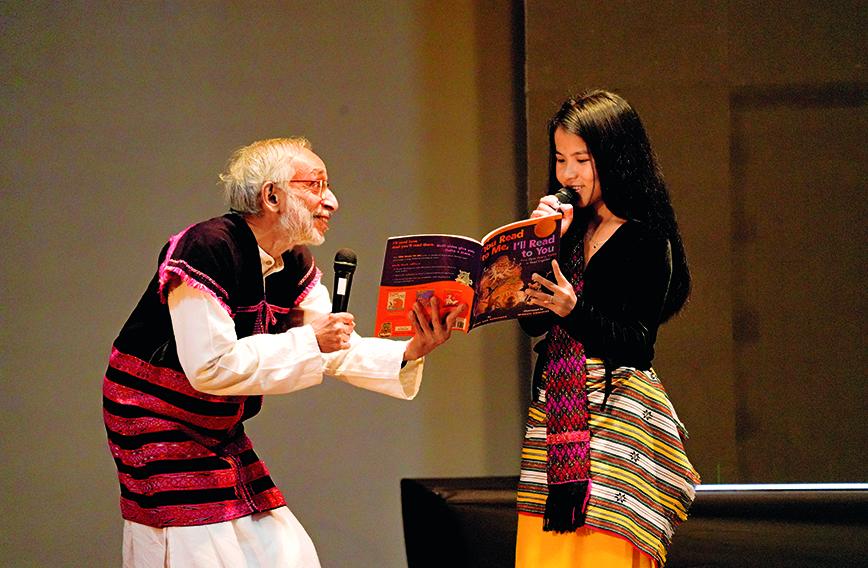

Uncle Moosa reads aloud with a student. The libraries are all about coming together for activities and shared learning

Books go far and wide the Moosa way in Arunachal

Civil Society News, New Delhi

LIBRARIES and bookshops are falling apart in big cities, but in Arunachal Pradesh a voluntary effort is spiritedly spreading the joy of reading among young people, reaching homes and government schools across the largely rural state.

Some 10,000 books are in circulation through a network of small community-run libraries and reading rooms with the Bamboosa Library in the town of Tezu, in Lohit district, serving as the headquarters.

As the books find their way across Arunachal, going from one hand to the next, they discover readers. Readers in turn get to experience the printed word and discover for themselves the world at large in many bits and pieces far removed from their remote lives.

It is a slow and unpremeditated process. A trickle in tune with the easy-paced and pastoral existence in the mountains. No instant results are expected. But a book in hand is the first step towards encouraging reading, spreading awareness and triggering transformations.

The libraries are also free-form. They come alive or go dormant, depending on local champions. Don’t expect to find extensive catalogues or a librarian behind a desk. It is all easygoing and relaxed with titles coming and going. The collections of books are varied — biographies, children’s stories, classics, novels. They are all donated by well-wishers in India and abroad. The Arunachal government library directorate has also provided books.

An important role the libraries play is in personal development. They are venues for the young to meet and interact. Read-aloud sessions spur children to do their own reading. Recitations and skits and plays help the young shed their inhibitions about making public appearances. In remote villages, where little else is available, the libraries, through the activities they promote, provide exposure and some excitement. They offer hope in settings where life, though familiar and secure, can also seem humdrum and remote, especially for teenagers.

Coordinating these enthusiastic but disparate efforts is Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor who is affectionately called Uncle Moosa. He is from Kerala, so what is a Malayali doing in the villages of Arunachal?

Coordinating these enthusiastic but disparate efforts is Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor who is affectionately called Uncle Moosa. He is from Kerala, so what is a Malayali doing in the villages of Arunachal?

He arrived in Arunachal in the 1970s from Kerala to serve as a teacher as part of a national effort to spread education and integrate the mountainous border territory with the Indian mainstream. He never went back and now at the age of 71 is part of the tribal cultural mosaic.

A short, frail man with a bird-like presence, Uncle Moosa has few needs and lives to dream. He dresses in a mundu and kurta and a cloth jhola is mostly his entire baggage. When he speaks it is in one continuous stream as though twittering.

He is much loved locally and welcomed into homes. Beginning as a teacher, he saw the potential of libraries in not just spreading formal education but also in helping the young along in complicated stages of their lives. As a result, he has seen more than one generation grow up and is inextricably a part of this extended family.

A few years ago, Uncle Moosa and the library movement entered the Civil Society Hall of Fame. Recently, he was a recipient of the Padma Shri. Our journey to Arunachal to discover him was full of wonderful surprises beginning with Uncle Moosa himself. We invariably don’t meet Hall of Fame entrants till we turn up to check them out. Uncle Moosa was never anything we imagined. Nor were the innocent and fresh faces of tribal youngsters at the libraries and schools. He had clearly created a rare chemistry among them.

“If readers cannot come to books, books must go to readers,” says Uncle Moosa. He explains that the Lohit Youth Library Network was launched in 2007 with this as its motto. The idea was to spread the joy of reading, through activities and personal example, and less to run libraries.

After 16 years, the network continues to be powered by activists. No one works for a salary. Nor does Uncle Moosa who is involved full-time but in an honorary capacity. As will happen with such elective arrangements, outcomes can vary depending on involvement. There will be strong spells and weak ones. But this is the serendipitous style that was envisaged for the network.

During the pandemic, everything came to a standstill, as was only to be expected. Now the network is slowly regaining a rhythm. The Bamboosa Library has moved into a new building. There is more space for its books, a small amphitheatre and a guest room where visitors can stay overnight if required.

The new building comes from the state government, which has over the years played an important role in supporting and encouraging the library network. The Lohit district administration has been particularly supportive. But the network is far removed from being a government-run programme and remains people-driven.

“All libraries are run by non-salaried youth volunteers as a service with no monthly honorarium to anyone,” reiterates Uncle Moosa.

“Volunteers, like human society, are evolving, changing. Hence there cannot be fixed volunteers at a library (in our network) unlike in an institutional library. So, some unit libraries remain dormant for some periods while some old units started in 2008-10 have become defunct for want of volunteers and mentors,” he says.

“Promoting reading habits among Arunachali students is done through activities by activists or volunteers using the library as a base within the library or outside, even at faraway locations. Thus, we encourage readers to emerge as reader-activists,” he adds.

Reading aloud sessions are found to be particularly useful in getting young people to engage with books. Reading together with others helps dispel inhibitions of not just reading but articulating words and speaking up. Currently, the Bamboosa Library is holding such sessions.

“After the pandemic, it was found that there were severe deficiencies in government middle-school students in reading aloud passages and pronouncing words. So, the Bamboosa Library tied up last year with the Denning College of Teacher Education in Tezu to involve trainee teachers as reader-activists by enhancing their reading aloud skills. This would benefit the trainee teachers as well as students in government schools. It would also give the Bamboosa Library a regular stream of new volunteers for its reading campaigns,” says Moosa.

It is also part of the network’s mission to produce and promote children’s literature in Arunachal’s languages. For this it has tied up with Tulika in Chennai. Hambreelmai Sai, a Mishmi folktale in the Mishmi Kaman language, has been produced as well as a biography of Mahatma Gandhi in five tribal languages.

Reading sessions and other activities serve as a spark for other community efforts and Uncle Moosa has been gifting books and magazines to get them off to a good start. With some handholding, people come forward. The Garung Thuk Community Library in West Kameng district has been around since 2018. The Free Library at Naharlagun in Itanagar opened in 2019. In Changlang district the deputy commissioner launched a community library volunteers’ initiative in 2021 and last year a New Age Learning Centre was opened at Miao in the district.

The Lohit Youth Library Network was designed to be free of encumbrances. It was envisaged as being without assets or weighty managerial responsibilities. Its role was to be motivational. The network’s strength was to lie in reaching corners of the Lohit-Dibang Valley region to inspire people to set up libraries and reap the benefits of reading.

Uncle Moosa describes the network as a “virtual entity” with libraries, including the big ones at Tezu and Wakhro, being owned and managed by separate NGOs and organizations. The network neither raises funds nor spends money. It doesn’t pay salaries or meet infrastructural expenses.

Volunteers who have been involved for some time and are now senior have formed an organization called the Forum of Library Activists. The Bamboosa Library, which is administered by Education Care for Kids, a registered NGO, is raising a corpus to which donations can go.

In Delhi, mentors and supporters of the library network have formed the Reading Promotion and Endowment Trust for Arunachal (REPTA) which has been a source of funding and receives donations that go to the network. Patronage has also come from the Surajmal Jalan Charitable Trust in Assam.

In this way the network says it has reached 9,000 young people in Arunachal over the years — an average of 600 a year. Are these numbers an accurate way of assessing its impact? Perhaps not. Having books in circulation so that young people can be exposed to them is an achievement. To do so joyfully is even more significant.

Comments

-

Amrita Patwardhan - July 9, 2023, 4:35 p.m.

Inspriring to know about this voluntary library work

-

Dr. Narasimha Reddy Donthi - July 8, 2023, 10:27 a.m.

Good effort. there are quite a few library movements and activists across the country. This, in Arunachal Pradesh, appears to be more sustainable beyond the individuals, who toiled in structuring it, especially Uncle Moosa. We need innovative ideas such as these to push books, reading habit among the youngsters who are largely addicted to mobile phones and the crap information that is 'shared' through them.