KANCHI KOHLI

Will the Narendra Modi government’s flagship projects like Sagarmala — an ambitious port modernisation plan — and the interlinking of rivers help us achieve the universal goals of sustainable development? If one goes by official documents which set the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in India, it is surely a big yes from the government’s point of view.

Like many countries, India is committed to achieving the 2030 Agenda by meeting the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The NITI Aayog is steering the task with comprehensive mapping of several initiatives by different ministries to understand how they correspond to the 17 SDGs and 169 related targets that India resolved to achieve in September 2015 at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York.

The genesis: The concept of sustainable development has been defined and debated since the late 1980s and formally adopted as a key driving force for all signatories of the Rio Summit in 1992. Its vagueness has been critiqued, its definition tweaked and invocation interpreted in various policies and judicial decisions in India since then. The National Environment Policy (NEP), 2006, tapped into this concept and so did the Supreme Court decision to allow mining in the Niyamgiri Hills in Odisha in 2007.

The seeds of what the NITI Aayog is attempting to achieve through various ministries and departments was sown at the Rio+20 Summit in 2012. Country representatives and civil society organisations met once again to understand where the world had reached 20 years after it committed to the idea of sustainable development. What has come into force today is a 15-year commitment to “end all forms of poverty, fight inequalities and tackle climate change while ensuring that no one is left behind”.

The mapping exercise: The NITI Aayog has undertaken a fascinating mapping exercise of SDGs, and responsible ministries along with various schemes and programmes that will help India achieve its SDGs. The document is titled “Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Targets, CSS, Interventions, Nodal and other Ministries” and can be downloaded from its website.

One of the mapping exercises relates to Goal 6 through which we are to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation”. A target (6.6) under this goal is to ensure that by 2020 all water-related ecosystems including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes are protected. It all reads fine so far, until the mapping leads you to the two government interventions that are to help achieve these goals. These are — the Integrated Ganga Conservation Mission and the Interlinking of Rivers.

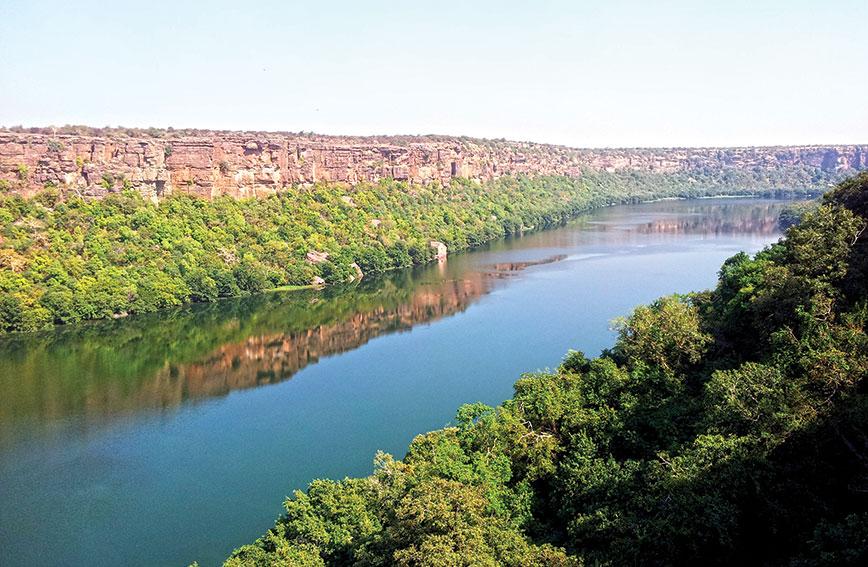

The contradictions start emerging clearly. The interlinking of rivers, always a controversial experiment, has been in the news more recently for the government’s push to make sure that the Ken-Betwa project is realised. Many regulatory and conservation concerns were unaddressed, yet the approvals just rolled in with the higher echelons of power wanting to try it out first and do a cost-benefit analysis on its impacts at a later stage.

This experiment, which will divert the “surplus waters of Ken basin to water-deficit Betwa basin”, is supposed to provide irrigation to Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. This sustainable development will ensure that an important tiger habitat within and around the Panna Tiger Reserve in central India will be impacted. The same area is recorded as a unique vulture habitat, a species already threatened in India. Several lacunae in background studies and impact assessments have been pointed out. This includes questions on the hydrological assessments of the project not taking into account the groundwater-to-surface flow dynamics of the area.

The depletion of groundwater is a huge crisis in India. In fact, the Model Groundwater Bill put out by the Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation (MoWR, RD&GR) clearly acknowledges in its May 2016 Groundwater Bill that a serious groundwater crisis is prevalent in the country “due to excessive overdraft and groundwater contamination”. But the same ministry has agreed to the interlinking of rivers as an intervention that will help achieve sustainable management of water and conserve water-related ecosystems.

Conflict of interest: The second irony lies in the interventions related to achieving Goal 14, which is to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. Amongst other initiatives, the flagship programme cited to achieve this is the Sagarmala project, launched in March 2015 prior to the formal agreement on the SDGs.

The Sagarmala project aims to develop new ports and strengthen inland linkages through road, rail, inland waterways and coastal routes. The NITI Aayog is a member of the Sagarmala Coordination and Steering Committee (SCSC).

All the six new ports that are under the Sagarmala project will almost entirely replace unique coastal and marine areas as well as threaten the homes and occupations of coastal communities practising fishing, salt production, farming and other livelihoods. These include Vizhinjam in Kerala, Vadhavan in Maharashtra and Tadadi in Karnataka. Each of these areas is also an ecological and scenic delight.

Such large-scale intervention replacing fragile habitats stands in direct contradiction of one of the targets embedded within the same SDGs (14.2). Here, India has committed to “sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems to avoid significant adverse impacts…”.

Contradictions are not uncommon in government documents, but the ones discussed above represent a conflict of interest. It is hard to see how Sagarmala will help conserve marine and coastal areas or how interlinking of rivers which depletes wildlife habitats and groundwater is an ideal initiative for water management.

But, then, the implementation of SDGs like the 1992 sustainable development principles is perhaps leading us to yet another review in 2030 that will build on the past and look hopefully into the future.

The author is a researcher and writer; Email: [email protected]

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!