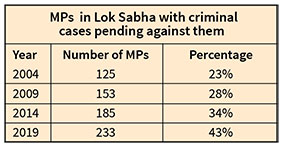

The number of tainted MPs in the Lok Sabha has consistently risen over the last four general elections

We, the warriors of democracy…

In his now famous speech to budding police officers in Hyderabad on how civil society groups can be subverted, the National Security Adviser, Ajit Kumar Doval, widely regarded as the third most important official in the security establishment, significantly said: “The quintessence of democracy does not lie in the ballot box … it lies in the laws which are made by the people who are elected by those ballot boxes … The new frontiers of war, called Fourth Generation of Warfare, is represented by the civil society….”

In his now famous speech to budding police officers in Hyderabad on how civil society groups can be subverted, the National Security Adviser, Ajit Kumar Doval, widely regarded as the third most important official in the security establishment, significantly said: “The quintessence of democracy does not lie in the ballot box … it lies in the laws which are made by the people who are elected by those ballot boxes … The new frontiers of war, called Fourth Generation of Warfare, is represented by the civil society….”

There are two fallacies in this formulation. One, ballot boxes are not of any use unless citizens, actually cast their votes into the ballot boxes. The other fallacy is about the people elected by those ballot boxes. What type of people are they? Data shows the number of MPs in the Lok Sabha with criminal cases against them has been growing. The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) collected this data from the self-sworn affidavits of candidates contesting elections to the Lok Sabha in compliance with decisions of the Supreme Court of India in 2002 and 2003.

Readers can judge the quality of “the people who are elected by those ballot boxes” from this table:

So, what’s new, you might ask? Till the year 2004, voters had no way of knowing what “type” of people they were casting their votes for in the “ballot boxes”. This was because of a specific provision in law which permitted a sitting legislator, convicted in a criminal case, to continue to be in that position and contest further elections, whereas a common citizen was barred from contesting elections for six years if convicted in a criminal case. But we are getting ahead of our story.

So, what’s new, you might ask? Till the year 2004, voters had no way of knowing what “type” of people they were casting their votes for in the “ballot boxes”. This was because of a specific provision in law which permitted a sitting legislator, convicted in a criminal case, to continue to be in that position and contest further elections, whereas a common citizen was barred from contesting elections for six years if convicted in a criminal case. But we are getting ahead of our story.

HOW IT ALL BEGAN

Around 1998-99, there were a lot of media reports about people with pending criminal cases against them contesting elections and getting elected. Around the same time, in May 1999, the Law Commission of India submitted its 170th report, Reforms of the Electoral Laws. In a comprehensive review of all the electoral laws one of the recommendations of the commission was:

“In the interest of transparency, we have also suggested provisions making it obligatory upon every candidate to declare the assets possessed by him or her or by his/her spouse and dependent relations and the particulars regarding criminal cases pending against him/her, in the nomination paper itself.”

A group of public-spirited persons decided to file a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Delhi High Court in December 1999, requesting the implementation of the above recommendation. The Delhi High Court, in a decision on November 2, 2000, upheld the petition and directed the Election Commission of India (ECI) to collect and make the necessary information available to voters.

The Union of India (UoI) filed an appeal in the Supreme Court against the Delhi High Court’s decision. Several political parties became interveners in the case, in support of the stand of the UoI, opposing the Delhi High Court decision.

The Supreme Court gave its judgement on May 2, 2002, upholding the High Court judgement, and directed the ECI to get information on a sworn affidavit from each candidate seeking election to Parliament or the state legislature, as a necessary part of his nomination paper, on the criminal, financial and educational antecedents of the candidate.

The ECI’s implementation of these directions made the entire political establishment very unhappy. In an all-party meeting on July 7, 2002, it was unanimously decided that the Supreme Court’s decision and the consequent order of the ECI would not be allowed to be implemented, and the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RP Act), would be amended, in that very session of Parliament if necessary, to nullify the Supreme Court’s decision and the ECI order.

A bill to amend the RP Act was accordingly prepared but it could not be introduced in Parliament as the Lok Sabha was adjourned sine die. The government then decided to issue an ordinance.

Given that the draft of the ordinance seemed to be prima facie unconstitutional, about 30 civil society representatives met the President and cautioned him about it. When the ordinance was sent to the President, he “returned” it. The Cabinet, however, sent it to the President again and he had to sign it following established convention. The Supreme Court’s decision of May 2, 2002, thus stood nullified.

The struggle did not end here. Three PILs were filed in the Supreme Court challenging the amendment of the RP Act. All three petitioners were civil society organisations: Association for Democratic Reforms, People’s Union for Civil Rights and Lok Satta.

The Supreme Court gave its judgment on March 13, 2003, holding that the amendment of the RP Act was unconstitutional and null and void. It restored the Supreme Court judgment of May 2, 2002, saying it had “attained finality” and that there shall be no appeal against that judgment.

This effort, from 1999 to 2003, is what enabled voters/citizens to know what type of people were “elected by those ballot boxes” and laws made by whom are the “quintessence of democracy”.

THE AFTERMATH

Yet the number of tainted MPs in Lok Sabha has consistently risen over the last four general elections! So, what impact has all this effort had? On the face of it, the proportion of people with criminal cases pending against them in the Lok Sabha has increased. But if one goes into some details of the electoral process, it is revealed that most of the reasons for this increase can be found in the laws made by the people who are elected by those ballot boxes!

Further, the root of all these mysterious outcomes lies in an institution called “political parties”. What political parties in India are, and what they should be, is best described in the following paragraph of the 170th Report of the Law Commission of India:

“If democracy and accountability constitute the core of our constitutional system, the same concepts must also apply to and bind the political parties which are integral to parliamentary democracy. It is the political parties that form the government, man the Parliament and run the governance of the country. It is, therefore, necessary to introduce internal democracy, financial transparency and accountability in the working of the political parties. A political party which does not respect democratic principles in its internal working cannot be expected to respect those principles in the governance of the country. It cannot be a dictatorship internally and democratic in its functioning outside.”

The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (NCRWC) chaired by the former Chief Justice of India, Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, in its report submitted on March 31, 2002, said:

“The Commission recommends that there should be a comprehensive legislation (may be named as the Political Parties [Registration and Regulation] Act), regulating the registration and functioning of political parties or alliances of parties in India.”

These recommendations were made in 1999 and in 2002, but it seems “the people who are elected by those ballot boxes” have not had the time or inclination to implement them.

SEVERAL INITIATIVES

On the other hand civil society activists, or shall we call them ‘Fourth Generation Warriors’, have been trying to get exactly the same done.

The ADR requested a committee chaired by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, to draft a bill to regulate the functioning of political parties. This committee drafted what it called the Political Parties (Registration and Regulation of Affairs, etc.) Bill, 2011. This draft bill has been shared with all the major political parties but none has shown any inclination of taking it up.

In addition, several initiatives have been made by civil society groups to cleanse the electoral and political systems. Some representative examples are listed below:

-

In June 2013, the Central Information Commission (CIC), in response to an application by ADR and S.C. Agrawal, declared in a unanimous, full bench decision, that the six national parties — the BJP, INC, BSP, CPI, CPI(M) and NCP — are public authorities under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005. All six parties refused to comply with the CIC's order. In May 2015, the same petitioners filed a petition in the Supreme Court to implement the CIC's order. The petition is still pending in the Supreme Court.

- In July 2013, the Supreme Court set aside clause 8(4) of the RP Act on petitions filed by Lily Thomas, a public-spirited Supreme Court lawyer, and Lok Prahari, a civil society group in Lucknow. As a result, sitting MPs and MLAs were barred from holding office on being convicted in a Court of Law.

- In September 2013, the Supreme Court ruled, in a PIL filed by the People’s Union for Civil Rights, that the right to register a “none of the above (NOTA)” vote in elections should apply and ordered the ECI to provide such a button in the Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs).

- Again, in September 2013, on a PIL filed by Resurgence India, another civil society group, the Supreme Court ruled that no columns or boxes should be left blank in affidavits filed as an essential part of the nomination papers, in terms of its judgment in the 2003 ADR case.

- In March 2014, the Delhi High Court in its judgement in a PIL filed by ADR, held that the BJP and the Congress were both guilty of accepting funds in violation of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act, 1976 (FCRA 1976), and directed the Ministry of Home Affairs and the ECI that appropriate action under FCRA 1976 be taken against them within six months of the judgment. Both the parties first filed appeals in the Supreme Court and then withdrew them. In the meantime, the government amended the FCRA twice, once with retrospective effect, eight years after the Act being amended had ceased to exist! The matter is still sub judice.

- In September 2017, ADR and Common Cause, another civil society group, filed a PIL in the Supreme Court challenging the constitutional validity of the Electoral Bonds scheme introduced by the government, enabling anonymous donations to political parties, in any amount, by anyone (including Indian and foreign companies with branch offices in India).

In an interim order on April 12, 2019, the Supreme Court said that “the rival contentions give rise to weighty issues which have a tremendous bearing on the sanctity of the electoral process in the country. Such weighty issues would require an in-depth hearing…”. But the learned judges of the Supreme Court have not had time to hear the petition till now, while elections continue to be held and unaccounted money keeps flowing.

The third highest functionary in the security establishment of the country seems to have a lot on his hands in dealing with Fourth Generation Warriors!

Jagdeep Chhokar is a former professor, dean and director-in-charge of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. He is a founder-member of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR). Views are personal.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!