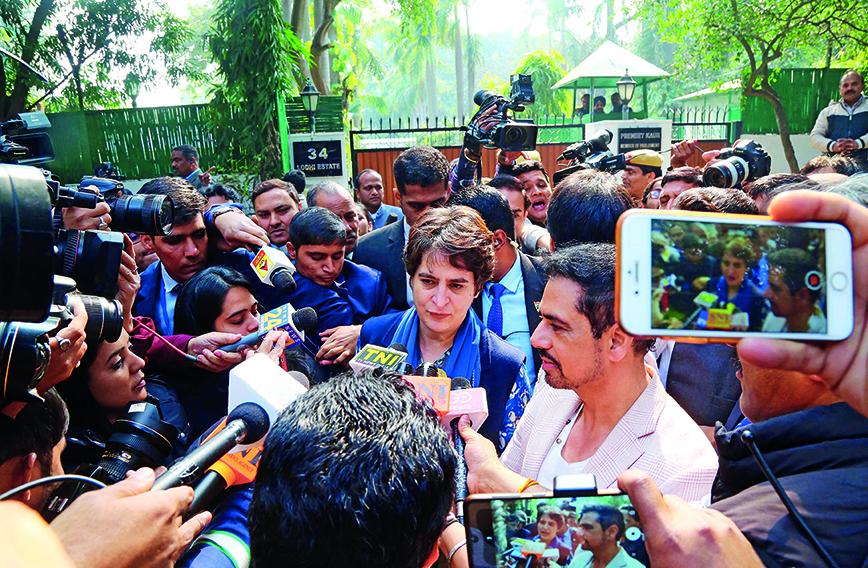

Smartphones, apps and social media make it possible for news to spread instantly

Media-mess age: fake news, garbled politics and more

Kiran Karnik

This is the media-mess age — the era when the media is making a mess of many things: news, politics, geography and the truth; possibly even ruining your dinner through constant “notifications” on your mobile, or screaming contests on TV. It has created fake news, garbled politics, annihilated distance and often exterminated truth. There was a time when news was factual, TV anchors were calm moderators, politics played out in a gentlemanly fashion and geography determined whom you could call through the telephone. That was, of course, aeons ago — the stone age of media.

Yet, not too long ago, media meant only the printed word, film (movies) and radio. Television had been formally launched in the country in the 1950s, but its reach was limited till the late ’70s, and its widespread penetration began only in the ’90s. In contrast, the past two decades have seen a media explosion: both in reach and completely new means. Often, the medium determines not only how we communicate, but also what — re-emphasizing the validity of what McLuhan said in 1964: the medium is the message.

Yet, conventional media have not altogether faded away. As many as 197 million households have TV sets, of which an estimated 98 percent are connected to cable or satellite (DTH). In addition, TV draws neighbours and friends who do not have a TV set. Radio continues to hold a fair number of listeners (estimated at 145 million), both in its old form as well as its newer FM avatar, which has a large urban, in-car commuter audience.

Despite TV and the new media, print continues to be important, with growing circulation for newspapers. Given their readership profile, it is not surprising that they wield influence that is disproportionately larger than what one might expect. An important reason for this is the quality of writers and analysis in the opinion and editorial segments, and the perceived authenticity and minimal bias in the news reports. Most TV news channels, on the other hand (and especially in the last few years), no longer even make a pretense of being objective. They reflect a strongly pro-government stance and an ideological slant, led by highly-opinionated and aggressive anchors, propagating their entrenched positions in discussions, and a definite bias in the selection and narration of news. This abrasive style and extreme positions, pioneered by one anchor became so popular that it is now emulated by almost all others on different channels. Apparently, it resonates with the audience and ensures higher ratings (TRPs) — the determinant for advertising revenue — without eroding credibility.

TV DOMINANCE

TV, with its reach and power, has now become an important influencer of decisions. The extent of attention it chooses to bestow on a particular event can make it loom large and multiply its impact. For example, Anna Hazare’s fast in Delhi may have been but one more of the many such in the national capital, covered — if at all — cursorily on TV (after all, Hazare was hardly a household name or a popular leader at the time). However, the near 24x7 coverage on TV brought it up front for the country, and drew ever larger crowds at the site. These two (coverage and greater crowds) reinforced each other and had a big impact on the government —probably being the catalyst for its electoral disaster. More recently, media coverage of the anti-CAA protest at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi not only made it a national — even international — event, but triggered similar sit-in protests in other cities.

TV also determines what is “news”. This agenda-setting role is exemplified by the coverage of the sad suicide of a young Bollywood actor, an event that might normally have merited a brief mention on one day. However, by sensationalizing it through various allegations and conspiracy theories, the story was given legs. Soon it became a daily feature on various news channels; linking it to the glamour and gossip of the film world made the story even juicier, with an additional positioning of an inter-state political dispute. Even the Supreme Court — which was taking up only some cases, in online mode due to the epidemic — thought the matter important enough to take it up. Doubtless, all this helped increase TRPs of various channels.

OWNERSHIP CONCERNS

There is another little-discussed factor: the ownership of TV channels. If a business channel is owned by a particular corporate house, would it not be biased in what and how it reports? Is there scope to slant and even manipulate news? For example, if a market rumour is reported and then quickly retracted as being incorrect, will someone buy or sell shares in those few minutes and make a killing? Can competitors be run down through planted or negative stories? These questions arise not just with regard to TV, but for all media, and is the reason why there has often (mainly in the past) been debate on whether there need to be guidelines or restrictions on media ownership.

TV and print, as noted, continue to be important, but there is little doubt that the new media is becoming dominant. It is not just their growing reach (for example, Facebook claims over 300 million users in India) which makes them a powerful force; it is also the characteristics of flexibility, interaction and instant feedback (through forwards and likes). Apps like Twitter, with its initial limit of 140 characters per message, cater perfectly to a generation with short attention spans. WhatsApp not only provides a means for instant messaging and free calls, but also — thanks to the camera integrated in the mobile phone — led to an explosion in exchanging selfies, including endless photos of oneself and of friends, or of food. To an older generation, this appears vain, narcissistic and inane, but the young love it.

TikTok and its clones transmuted the Twitter concept to video, and these short-video sharing apps stormed the market. Within a year of its launch, TikTok (now banned by the government because of data security concerns) saw more than 600 million downloads in India, over a third of those world-wide, according to media reports. These apps have enabled and encouraged people to upload and share their performances, unearthing dancing, singing and other talent from all corners of the country. In the process, some of them have garnered a vast following and become stars.

Social media has created a whole new set of “influencers”: those who attract a large number of viewers or likes. Of course, these influencers, unlike TV anchors, are used almost exclusively for commercial purposes. Advertisers now pay them to promote their products, making these influencers the new endorser-celebrities. The fact that these platforms are in the form of apps on mobile phones makes them easily accessible on all the 395 million smartphones in the country. Little wonder then that many of these apps are hugely popular.

These aspects of social media are harmless and many are, in fact, beneficial. The ability to easily send and instantaneously receive messages, bills, photographs or videos, at no cost, has been a boon for small business. Free video calls and immediate sharing of news or answers to queries are immensely useful. The facility to create special-interest groups has helped to keep friends and relatives, dispersed around the country — or the world — in immediate touch with each other, and re-create a bonding that may earlier have been loosened by geography. At the same time, very local uses (for example, a group comprising residents of an apartment complex) is of great utilitarian value. A sudden need for a hammer can be met in minutes when a request is posted on the group, as can a requirement for the contacts of a pediatrician.

FLOOD OF FORWARDS

The new media, though, are hardly an unmixed blessing. The creation of like-minded groups has led to floods of forwards which reinforce already prevalent opinions, resulting in an echo-chamber effect and promoting stereotyping and bigotry. False news and rumours can have a devastating effect, as we have seen in numerous examples in the country, including some that triggered lynching and riots. Instances of this nature, and of allegations that foreign powers sought to influence the US presidential elections four years ago, have led to major social media companies like Twitter and Facebook putting in safeguards. False or incorrect news may be flagged, hate posts taken down and serious offenders barred.

The guidelines and actions by the companies concerned raise some serious issues. On the face of it, what is being done can be considered an appropriate response. However, should these companies have the right to decide what is appropriate and to censor posts on what has become a public platform? All the more so, when they are so large and enjoy a near-monopoly in their segment? Can they play favourites and favour one point of view and remove another because they deem it objectionable?

The recent controversy regarding Facebook not taking down a vitriolic and communal post by a politician, despite an internal recommendation to do so, has provoked a discussion on free speech. Such a debate is overdue, given that free expression seems to be increasingly curbed by trolling, threats and sedition cases. While the supporters of one party have been called out for such tactics, others are hardly angels — doing the same when they can. True supporters of freedom are, indeed, scarce.

The Facebook story causes deeper concern on two other counts. First, that a senior person decided not to act because she felt that it would offend the government and thus affect their business prospects — signaling that such decisions (regarding what is objectionable) are made on commercial considerations. Does this imply that Facebook will carry any post as long as it furthers their business interests? Second, that taking any action against the post of a ruling party functionary would affect their business — indicating that being on the right side and propagating the views of the ruling party representatives is important for business. If such a perception is correct, it impinges on a basic premise of democracy: the right to express a view contrary to that professed by the government of the day, and yet get equal treatment as others. Kow-towing to the government is not a monopoly of MNCs: in India it has long been a tradition for business leaders to publicly always side with the government (for example, by giving every Budget 8 or 9 out of 10!). However, when powerful media does so, in unison, it spells danger for democracy.

The new media provide valuable services at no monetary cost, but you do pay: through your data. Social media monetizes your data, sometimes selling it to third parties. Through the fine print which hardly anyone ever reads, your private data is generally used with your consent. Such data about you can, with the help of new analytical and behavioural tools, be used to predict how you will act and, possibly, even influence that.

Given the size and power of media companies, should there be some form of regulation? Will this mean transferring even greater power to the government? What should be the rules on collecting, storing, transferring and using data about individuals? These and other concerns deserve thought and debate. With all this one wonders whether to be cognizant of the media message or of the media-mess age.

*Kiran Karnik is an independent strategy and public policy analyst. His recent books include eVolution: Decoding India’s Disruptive Tech Story (2018) and Crooked Minds: Creating an Innovative Society (2016).

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!