The good listener who took science to people

By Dunu Roy

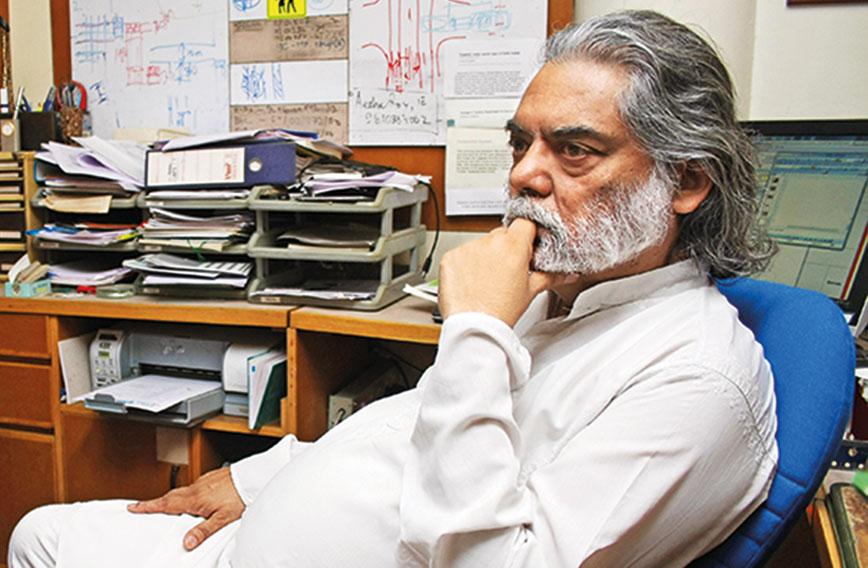

ON May 21, an early Friday morning with the rain clouds skittering away across blue skies, Prof. Dinesh Mohan died in hospital, deeply mourned by family, friends, colleagues, and students. Much has been written about his expertise in injury prevention and safety, and his international stature as a much sought after (and provocative) speaker. There is, however, a lesser known area of his work that has not been much discussed.

Shortly after his return from the US he signed the Statement on Scientific Temper in 1980 that spelled out why science had to analyze and expose the barriers that stood in the way of a rational solution to societal problems. But within two years it was obvious that he had also understood that these barriers were primarily erected against the poor. So he co-founded the Sanchal Foundation in 1982 with the objective to ‘promote, foster, aid and assist research for the extension of knowledge’ but with the clear mention that this knowledge had to be for the advancement, better education, working and living conditions, and health of poor people.

Two years later political riots erupted in Delhi, killing hundreds of Sikhs, and he became part of the Nagarik Ekta Manch that extended whatever help they could. But to explore the social barriers that led to the riots he also became a member of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties-People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUCL-PUDR) team led by Prof. Rajni Kothari and advocate Gobind Mukhoty, that went deep into the colonies of Delhi and the villages of Punjab to come out with the searing report, “Who are the Guilty?” The report contained the essence of scores of interviews with the families of those who had been murdered to document who had done the murdering.

He was invited by the eminent orthopaedic surgeon, Dr P.K. Sethi, to do an analysis of the artificial limb that Dr Sethi had developed. Dinesh visited the workshop in Jaipur and was deeply impressed by how ‘ordinary people’ were able to make limbs, train amputees, share their misfortune and encourage one another, and participate in the excitement of teaching others how to walk and giving them hope in coping with the world. But what seems to have struck home was Dr. Sethi’s counsel, “We have stopped being good listeners and have forgotten the art of communication with our patients, an art which plays such an important role in the equation for recovery.”

This act of listening prompted him to reconsider how science could actually be created by ordinary people and led to the founding of the People’s Science Institute in 1988, of which Dr Ravi Chopra later became the first director. Then he and his colleagues went back to the villages of Haryana and Punjab to listen to those who drove the tractors, ploughed the fields, sprayed the pesticides, harvested the crops, threshed the fodder, and winnowed the grain. That, in turn, culminated in the two landmark reports on “Pesticides and Physical Disability” and “Safety of Agricultural Implements”.

Once a scientist becomes sensitive enough to begin listening, however, the learning cannot stop at the boundaries of his or her scientific discipline. Which is why Dinesh moved further afield to contribute to the report on “India’s Kashmir War”, the formation of the Pakistan-India Peoples’ Forum for Peace and Democracy, the setting up of the Permanent People’s Tribunal on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights (which examined the Bhopal gas leak), and an analysis of the Godhra train burning—none of which had much to do with biomechanical engineering, or traffic injuries, but sharpened the balance between science and society.

In 1997, appalled by the paucity of research in his chosen field, he formally initiated the Transportation Research and Injury Prevention Programme (TRIPP) at IIT Delhi. By a strange coincidence, the interdisciplinary nature of this programme seemed to match very well with the coming together of several groups in the city representing the transported and the injured to form the Sajha Manch. There were people who were being summarily evicted from the slums; there were those whose unauthorized colonies were being targetted with displacement; there were workers whose livelihood was at stake as thousands of factories were closed down; vendors, hawkers, rickshaws, autos that were being moved off the roads; the shift from diesel to CNG: all being done for ‘cleaning’ the environment, but obviously for the purpose of ‘cleansing’ the city before the Commonwealth Games of 2010.

Dinesh was invited to meetings of the Manch and listened very carefully to what was being said by those whom he called ‘vulnerable road users’ and then stepped in to subtly press TRIPP into action. Sandeep Gandhi was roped in to digitally map the slums and unauthorized colonies; Geetam Tiwari and her students began studying how cycle paths would benefit this class of road users, and what was the role of hawkers and vendors in the service infrastructure; TRIPP involved the Manch in a study of the Delhi Development Authority's differential norms with respect to water, sanitation, and transport use; Dinesh himself led a study of the needs of auto-rickshaw drivers; the idea of the Bus Rapid Transport corridor began evolving; Sudipto Mukherjee was persuaded to develop a capnograph for measuring the energy expenditure of workers; and collectively they contributed to the Manch’s critiques of the Delhi Master Plan, Commonwealth Games, the National Urban Renewal Mission, the Metro, and the Smart City.

As TRIPP evolves from a programme into a centre, it would be well to remember that the foundations of good science are based on listening to, and in collaboration with, the people who lie on the other side of the social barrier.

Comments

-

smita - July 12, 2021, 1:22 p.m.

The expanse of Prof Dinesh Mohan's work is astounding. He actively involved himself with all the major social upheavals of the last 3-4 decades. He provided solutions to the issues and succour to people at the receiving end of things.

-

Ramakrishna Naidu - June 28, 2021, 10:16 p.m.

I would like to label this a very concise tribute to the professor!

-

manohar notani - June 28, 2021, 10:04 p.m.

REAL AND RICH TRIBUTE TO PROF. DINESH MOHAN