A caring industrialist who truly believed in giving

By Umesh Anand

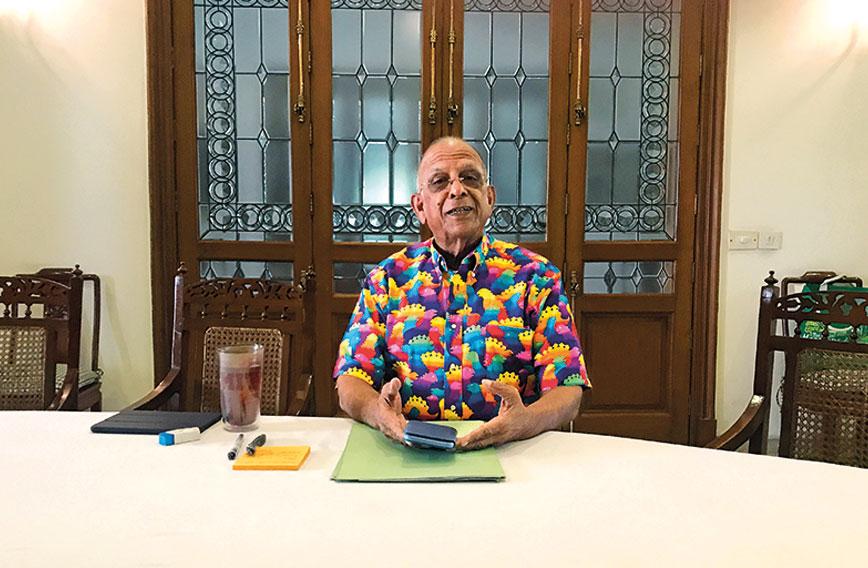

AMONG the many remarkable people that the second wave of the virus carried away with it was Siddharth Shriram, a close and much valued friend of this magazine.

At first glance, it would seem that we couldn’t possibly have much in common. He was an industrialist who belonged among the rich and powerful in the country. We are journalists who spend our time telling the stories of those who have no social heft. We belonged to different worlds. Born in 1945, he was also a generation apart from us.

But Siddharth (Chiku to childhood friends and family) became part of our world in an immersive way. He was proud of our magazine, respected our independence and cared as much as we did for our stories.

Money wasn’t the basis for our association though in his personal capacity and with advertising from his companies he saw us through difficult times when no other help was forthcoming.

Support from Siddharth came nicely — in a happy and unfussy style. There was no hidden design. He didn’t ask for anything in return. Deep down perhaps there was the satisfaction of being part of an idealistic and purely journalistic effort. There is a certain charm and romance to bringing out a magazine with limited resources.

He had a fascination for journalism, which he never adequately pursued in his youth. Late in life Civil Society was perhaps an opportunity to relive that dream in much the same way as he reported on golf for a pink paper.

We first connected over our book Inventive Indians: 32 Stories of Change. It was then only available in a coffee table edition. He bought some copies and we met thereafter.

Books remained a common interest — all kinds of books. The Secret Life of Trees on our shelves remains a reminder of Siddharth’s eclectic interests. He was a firm believer in natural medicine and the value of medicinal plants.

Siddharth Shriram was the grandson of Lala Jwala Prasad and Lala Shriram and the son of Lala Charat Ram. He had a management degree from MIT, graduated from St Stephen’s College and went to Doon School.

A reluctant businessman, he ended up running companies across sectors, brought international companies like Honda to India and was closely networked where it mattered.

His privileged background didn’t come in the way of him being considerate to those who were less fortunate than him. He treated everyone with respect. He also ensured that his companies were not just conscious of their social responsibilities, but also creative and relevant in the ways in which they engaged with society.

His company, Usha, for instance, set up sewing schools in remote parts of the country to give women skills which could lead to employment opportunities.

The sewing schools serve as a natural extension of the business that Usha does as a company. By helping women to add to family incomes, the schools empower them gently and set in motion a process of long-term change.

It is a unique initiative, which, he would proudly say, his son, Krishna, has built on with passion, having taken over from Siddharth in the business much before his passing. In a perfect example of upscaling, the sewing schools have been linked to commercial designers and work done by them has featured in fashion week shows.

Similarly, Siddharth set up reading rooms which also served as information centres near his sugar mills so as to inculcate the reading habit and help people in villages connect with the world at large. Schools were also set up.

When we were launching ‘Civil Society Lectures’ in Delhi University in association with Miranda House, we asked Siddharth to speak on the social responsibility of companies.

His lecture had near about a hundred young people listening without leaving and then asking questions. It was a grand success. He reminded them that giving back to society had little to do with how much wealth one had. It was more a question of personal orientation. When his grandparents and parents put money in social ventures, in fields such as education, they weren’t as wealthy as they were to become. But they nevertheless created social assets.

He also told his young audience how disappointed he was with the managements of companies which had laid off people during the pandemic and the downturn in the economy. In contrast, his family had decided that no one would be made jobless and instead all employees would be supported in every way, particularly if they got infected by the coronavirus.

Giving was a way of life for him. He didn’t let it weigh him down. Being ponderous was not for him. Life was to be enjoyed. He liked to get on with things.

As he said to his young audience at Miranda House: Neki karo aur bhool jao (do good and forget about it).

Comments

-

Evita Fernandez - Aug. 15, 2021, 11:17 a.m.

Thank you for sharing this information on a life well-lived. Certainly an inspiration for us all. You were privileged to have him as a friend and benefactor. I was particularly drawn to the line:"giving back to society has little to do with how much wealth one had. It was more of a personal orientation"

-

Vinod Arora - July 5, 2021, 7:23 p.m.

One & only Siddharth Shriram, a noble soul with great sense of compassion and humour!

-

Vinod Arora - July 5, 2021, 7:22 p.m.

One & only Siddharth Shriram, a noble soul with great sense of compassion and humour!

-

Edward M. Shumsky - June 24, 2021, 11:24 p.m.

What a beautiful description of Siddharth, a grand but gentle man.