In search of the India story beyond the headlines

Rita & Umesh Anand

IT was a well-attended event in the amphitheatre of the India Habitat Centre on Lodhi Road, a posh part of New Delhi. In attendance, however, were not the well-heeled and influential people you might have expected to find. Instead, there were slum-dwellers onstage, and they had brought along their own audience of ragpickers and daily-wage earners.

The event, cheekily named Shehr.com, had been organized by the Hazards Centre, a small NGO, so that the poor could voice their views on what life was like for them in Delhi and what their expectations were. There were short plays and some speeches by the slum-dwellers and the odd performance by university students.

The Delhi government, then under the Congress, had circulated a draft master plan for transforming Delhi into a world-class city by 2010, when it would be the venue for the Commonwealth Games.

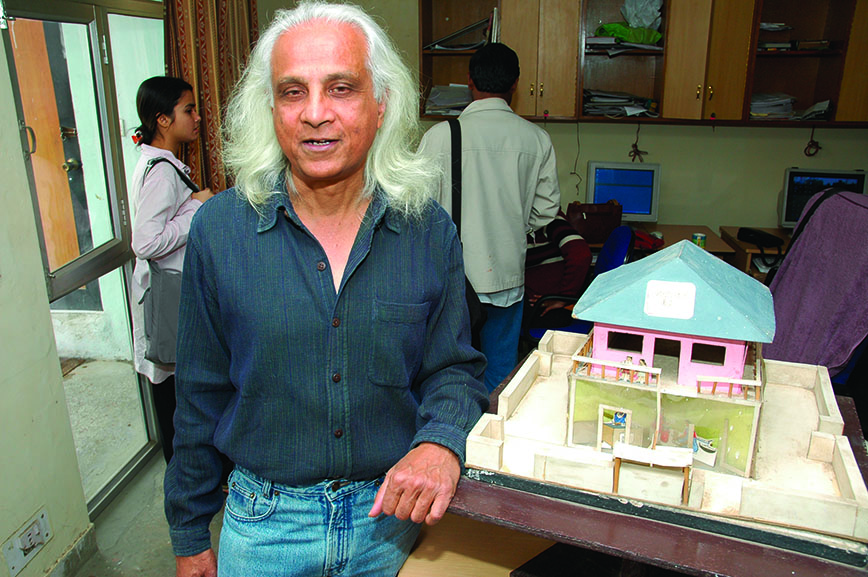

The government was seeking public opinion on the draft. The Hazards Centre wanted the poor to be heard. To make their point, Shehr.com had been organized at the Habitat Centre — no less. The NGO was devoted to making cities inclusive through better design and access to infrastructure. Its young activists, led by the ageing but long-haired Dunu Roy, were asking the question: “Whose city is it, anyway?”

Dunu Roy: What is a world class city?

Dunu Roy: What is a world class city?

On the same day, on the manicured lawns of the Habitat Centre, across from the amphitheatre, an entirely different kind of event was taking place. Buffet counters were loaded and set to serve a sumptuous lunch and there was an impressive array of spotless white tables. TERI, the energy NGO, was holding a conference on sustainability and the midway break in the proceedings was coming up when the delegates would be convening for lunch.

It was difficult not to notice the sharp contrast between the two events. Both were about sustainability, but the participants belonged to separate worlds and, of course, their perspectives were different. The slum-dwellers came out of the neglected peripheries of the city. They were interested in basic necessities and had perhaps never before set foot in the India Habitat Centre. On the other hand, TERI’s gathering, and the NGO’s own leadership, was sophisticated, urbane, well-connected and technologically driven.

It was February 2006. Our magazine had completed two years and a few months at the time. We were finding our feet. But, as journalists, we were enthralled by the complexities we were seeing. We put

Shehr.com on the cover of our next issue with the headline: “What is a world class city?”

It was the kind of India story that went beyond everyday headlines. We had started Civil Society to seek out the voices that don’t get heard and give them a chance to be among the headlines. With India urbanizing somewhat rapidly and haphazardly there was a need to understand the growth pangs of cities a lot better.

FIRST ISSUE, KEJRIWAL

Civil Society was launched in September 2003 as a monthly magazine. Our very first issue had Arvind Kejriwal on the cover. We found him in Sundernagari, a slum in northeast Delhi, conducting a campaign against municipal corruption. He was then an officer of the Indian Revenue Service, on leave from the government.

Back in 2003: Arvind Kejriwal and the Parivartan team at their office in Sundernagari in northeast Delhi

Back in 2003: Arvind Kejriwal and the Parivartan team at their office in Sundernagari in northeast Delhi

Our story was on the right to information (RTI) and we found in Kejriwal the perfect face to take readers into this complex and little understood subject. The cover was headlined: Taxman’s burden.

RTI wasn’t as yet a Central law but a campaign for it was already underway. State governments were under obligation to have better transparency because of World Bank conditionalities. Delhi already had a state-level RTI law.

Kejriwal’s NGO, Parivartan, had opened an office in Sundernagari. The issues he took up were corruption in municipal contracts, lack of accountability of officials, the right of the citizen to be heard, food disbursed through ration shops and the quality of civic assets.

These very issues became the planks on which Kejriwal would pursue his political career successfully. He still commands an unsurpassed following among voters in Delhi because of the grassroots concerns his Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) raises and his promise of empowering the common citizen.

As a social activist, Kejriwal and Parivartan were supported by Aruna Roy, Nikhil Dey, Shankar, Shekhar Singh and others associated with the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan or MKSS. They had already been campaigning for RTI. They brought to Sundernagari the device of the public hearing or jan sunwai to create awareness.

A jan sunwai: Jean Dreze, Aruna Roy, Shekhar Singh and Colin Gonzalves

A jan sunwai: Jean Dreze, Aruna Roy, Shekhar Singh and Colin Gonzalves

We went on to cover the India Against Corruption movement, the Lokpal agitation with Anna Hazare and the coming to power of AAP with its promise of a new politics in the country. Our coverage included other voices as well, including those who had reservations about the selling of the Lokpal idea as the solution to all corruption.

In 2003, governments were beginning to recede and yield space to the private sector. Utilities were changing hands. New technologies were being born. To maintain a balance, social enterprises and activists were needed more than ever. Among them were changemakers with solutions to longstanding problems of development.

As journalists we found these stories exciting and worth exploring, more so because other journalists weren’t seeing the potential in them. Kejriwal, Aruna Roy and others, for instance, came to be visible in the big press only much later. We felt that in a crowded media market we would also be breaking new ground and carving out a unique space for ourselves. We would be noticed as a publication and so also the changemakers we were writing on.

OUR CHOSEN WAY

The stories we began doing were unusual. With blinkers gone and now masters of our own brand, we were free to make our own choices, chart our own course. We covered initiatives that other publications dismissed as being too small or insignificant. By employing mainstream skills and clear editorial values we raised the bar for such stories.

Call it prescience, but while our first cover story was on RTI and featured Kejriwal, our second was on Sheila Dikshit who was involving the RWAs (Resident Welfare Associations) of Delhi in governance and our third was on NGOs in politics. All three cover stories were to play out majorly in the months and years to come.

It was also important to us that our stories be done on merit. So, there were stories we didn’t want to do. We held back from a bleeding-heart approach. We didn’t see value in regurgitating problems. Instead, while presenting problems, we looked for solutions. Scandals and exposes were not for us either. Professionally-shot colour pictures and modern layouts further shaped an environment of optimism.

We found Civil Society increasingly being seen as a solutions magazine of sorts though that was only partly our goal. Readers began coming back to us, saying: “You give us hope. There are so many good things happening in the country.”

We now have a sizeable archive of rare pictures and stories that provide a unique and valuable record of India in transition over the past 20 years. There are scores of significant interviews. The India story post economic reforms would be incomplete without acknowledging the contribution made by NGOs, activists and public-spirited individuals in shaping a modern, inclusive and forward-looking country.

A DEFINITION

An initial challenge was to come up with a definition of “civil society” — both for ourselves and for readers. The term “civil society” wasn’t as widely understood in 2003 as it is today and we would be very often asked what it meant. Early in our journey, we decided that civil society couldn’t be restricted to a handful of prominent, mostly urban, organizations and individuals. We felt it should include the large number of small groups and individuals trying to make a difference across the country. And India had many working far from the limelight.

The role of civil society is to be a pillar in its own right by holding the private sector and the government to account. It protects our shared values when they are in danger of being trodden upon. NGOs and activists do this by being whistleblowers, filing public interest litigation and generally mobilizing opinion against transgressions.

Civil society may not necessarily have a single voice because there will be disparate views and positions on issues as they arise. However, a broad base of values that define the general good is what holds the social fabric together despite differences that may exist and keep manifesting themselves.

Anna Hazare being feted in Delhi during the Lok Pal agitation

Anna Hazare being feted in Delhi during the Lok Pal agitation

Activists are also always in a fragile position because they aren’t elected and assume the role of speaking for the general good. This leaves scope for misrepresentation. But all things considered, a vibrant civil society is essential for the healthy functioning of democracy.

Social enterprises come up with innovative solutions to the problems of development. They speed up inclusion by closing last-mile gaps in the bestowing of rights and delivery of services. They innovate and think ahead for the general good — something governments and corporations don’t do well enough on their own.

There are also individuals who speak up and do their bit in the course of their professional lives. They, too, play a civil society role. It could be a businessman, doctor, lawyer, engineer, government servant or code writer. They could be lending their skills to a good cause or simply setting an example by being inclusive or using specialized knowledge for the public good.

Small endeavours tend to be driven by passion and designed to meet some local need. But in doing so, we have found, they often also address national-level concerns in healthcare, education, environment, water, nutrition, agriculture, digital access and so on. They have the potential to be shared, adapted and scaled. Shining a light on them is important so that they become known.

We have found from our stories that water harvesting in Rajasthan elicits a response from north Karnataka. The building of low-cost bridges for cut-off communities in Karnataka evoked an interest in the northeastern states. Affordable housing has takers everywhere.

We have witnessed people eager to learn from one another and, more interestingly, governments willing to learn from innovators. This is civil society at work and social interaction at its creative best.

PATIENCE IS NEEDED

It takes time for change to happen, but it finally does arrive. In 2006, when we first reported on Preeti and Kabir Vajpeyi, they couldn’t find state governments that were willing to adopt their low-cost ideas for improving schools.

As architects they had shown in Rajasthan what could be done to transform school buildings for as little as Rs 20,000. Their programme was called Building as Learning Aid or BaLA. It involved brightening up exteriors with paint and using everything from window grills to doors and floors for learning. School compounds were revived so that children could play joyfully in them.

Persistence paid and now BaLA is widely used across states. A deputy commissioner in a northeastern state we were interviewing told us he relied not just on NGOs to get children to school but had on his own initiative implemented BaLA because he recalled Kabir Vajpeyi lecturing on it at the IAS academy.

Innovators are by definition ahead of the times. Governments, on the other hand, tend to be sluggish in getting the message. It is not as though individuals and groups seeking to bring change are always right. But without doubt governments need to increase their capacity to engage productively with new ideas.

Activists, on the other hand, have to see patience as a virtue and a necessity. Our dear friend and advisory board member, Anupam Mishra, would say: “NGOs think change comes overnight. It doesn’t happen like that.”

When Ela Bhatt, the creator of SEWA, talked about women’s rights and employment 50 years ago in India she was way ahead of the curve on this issue. It is only now that the economic potential of women is being recognized and that too perhaps not as widely as it should be.

Recently we did a story on how SEWA had helped women in Kupwara district, near the Line of Control in Kashmir, acquire skills and have incomes and assert their identities within their families and the community. Having a livelihood has transformed the lives of these women. But it took SEWA all of 13 years to achieve this.

The women in Kupwara had grown up in the midst of extremism and anti-India sentiments. They were suspicious of anyone reaching out to them. SEWA had to bring them to Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Pune and Delhi to show them what they were missing out on. They were introduced to the empowering work done with other women. The experience changed the way they regarded India. The exposure was liberating in personal ways as well — for instance, the experience of being on a seashore and being away from home.

Supporting SEWA in this initiative all these years has been the Union government’s Home Ministry. The current one under the BJP has been the most supportive — surprising as that might be to many. Clearly, much is gained by governments that let activists take the lead in certain contexts.

HEALTHCARE

It is not as though governments always listen. Healthcare is an example where a reorientation is desperately needed. Our coverage of healthcare has been extensive. We have focused on the voluntary and government sectors to find what works.

Small hospitals with public spirited doctors whose stories you will find in our magazine have for long been showing the way to reach large numbers of people who cannot afford expensive private care. The pandemic showed the importance of readily accessible primary care. The mission hospitals, outfits like Doctors for You, the rural surgeons’ movement and the innumerable excellent doctors in the government system need to be looked at more closely so as to bring back values to the medical profession and place healthcare above being a business. A robust economy first has to have healthy people.

MOVEMENTS AND LAWS

Apart from RTI our magazine covered movements for the right to food, education, disability employment, rural employment and street vending. We also reported on the persistent efforts by Breastfeeding Network of India that finally brought about the ban on promotion of baby food.

We were there as these movements were gathering momentum. We were witness to how much effort and patience went into framing laws. The laws that got passed at the time like RTI, MGNREGA, right to food and right to education addressed people’s issues and came from the grassroots. They were opposed by the bureaucracy and economists and lobbyists for industry as well.

At no stage was it easy even though there was a Congress government in power and it was expected to be amenable to suggestions of activists. Perhaps they could have been better framed if consultation had been yet wider as in the case of the right to education. But they have proved to be important pieces of legislation that have served the country well. They have been used not just by the Congress but now by the BJP too.

ROLE OF NAC

The impression often is that the National Advisory Council (NAC) pushed policies and legislation through. From where we could see things it didn’t seem entirely so. From the RTI agitation, when the law was getting stuck, we have pictures of posters with slogans like: “Sonia Gandhi chuppi chodo” or “Sonia Gandhi break your silence”.

Without doubt the NAC gave NGOs enormous access. But activists also had to deal with government, at least from what we could see. There remains a need to understand a device like the NAC a lot better. It served an important role in giving voice to civil society. In doing so, did it undermine government is a question that remains to be answered.

It is important not to bore the reader. A mix of stories works well. It helps to have cinema, books, new-age businesses, recycling, solar power, electric vehicles, healthcare and disability art in addition to stories of empowerment and social justice.

The Indian civil society space is rich and varied. There are changes in consumer preferences. Entrepreneurs come along with great ideas. Established businesses go through changes. New technologies change social behaviour. In an emerging economy getting globalized and experiencing high growth, nothing is at a standstill.

Our Living section has tried to reflect these changes through the stories of people. Our coverage of cinema has not been only of alternative films and documentaries, but also of Mumbai and the emergence of directors like Anurag Kashyap during their early rise.

Under books we have done reviews and spoken to authors who might have otherwise gone unnoticed. For all the digital reading that happens, print is very alive. A feature on preloved books had readers writing in.

It has also been a wonderful experience reporting on new-age businesses whose leaders and founders are educated, socially driven and respectful of the natural environment. Such businesses may be relatively small, but they are incredibly valuable.

Raj Seelam’s 24 Mantra is an organic food company. He has built it from scratch. There is the Black Baza Coffee Company, which describes itself as an activist company selling sustainable coffee. Its founder is Arshiya Bose, who decided to connect consumers to small coffee growers in the Western Ghats. Vinod Kumar and Priya Prakash of Naturally Yours are in the business of healthy noodles and pasta from millets, red rice and so on.

Tushar Devidayal produces solar refrigerators which can be used in villages. There are solar dryers for which the Sant Savta Shetkari, a farmer-producer company, sought out S4S Technologies. Women farmers in Bundi in Rajasthan come together to create an enterprise to sell their produce. We have in this issue the story of rangSutra in the words of its founder, Sumita Ghose.

HALL OF FAME

The Civil Society Hall of Fame became our magazine’s annual event for recognizing changemakers from all over the country. After a recognition ceremony, Indian Ocean, the iconic fusion band, would perform in what we called the Everyone is Someone Concert. It used to be among their best performances.

The women of Bundi being felicitated at the Hall of Fame event in Delhi

The women of Bundi being felicitated at the Hall of Fame event in Delhi

Entrants to the Hall of Fame can’t apply. They can’t want to be famous. They are identified for their work through our networks. Mostly, they are surprised that they are on any kind of list at all.

Over the years, the Hall of Fame has come to include doctors, scientists, insurance agents, farmers, vaidyas, human rights activists, tribal leaders, government schoolteachers and headmasters, social innovators, administrators.

The list is too long to be reproduced here. We have brought them to Delhi and feted them at an event in the heart of the capital. They have come dressed in their own local styles and spoken about their work in their own local languages, requiring translators for the Delhi audience.

If the Hall of Fame has drawn a large audience each time it is because the diversity it showcases is magical. The people it honours are each different from the other, exceptional in their own ways. They represent the great diversity and energy that exists in the corners of our country.

Twenty years is a fair length of time to keep a magazine running. Journalism offers a perch like no other from which to observe a nation caught up in the processes of change. We have more stories than we can tell and an archive with many gems.

If there is one thing we would like our magazine to be known for, it is that it offers a unique perspective into Indian civil society. It is a hopeful perspective that throws light on the many Indias and the many Indians who make our nation and society so vibrant, so creative and yet so challenging. We would like to see ourselves as messengers from this changing India.

Comments

-

Shashank - Feb. 5, 2024, 10:32 a.m.

I loved the title because this magazine has always been seeking out stories that one barely gets to see elsewhere. Kudos to you for reaching out beyond headlines and bringing the lesser known unsung heroes among us into the much needed limelight.

-

Sanjukta Bose - Feb. 5, 2024, 10:30 a.m.

So well articulated and engaging. It really does bring out the essence of what this magazine stands for. Thank you for keeping this independent endeavor up and running for 20 years. Wishing Civil Society a very happy anniversary and hope to read more such pieces in the years to come!