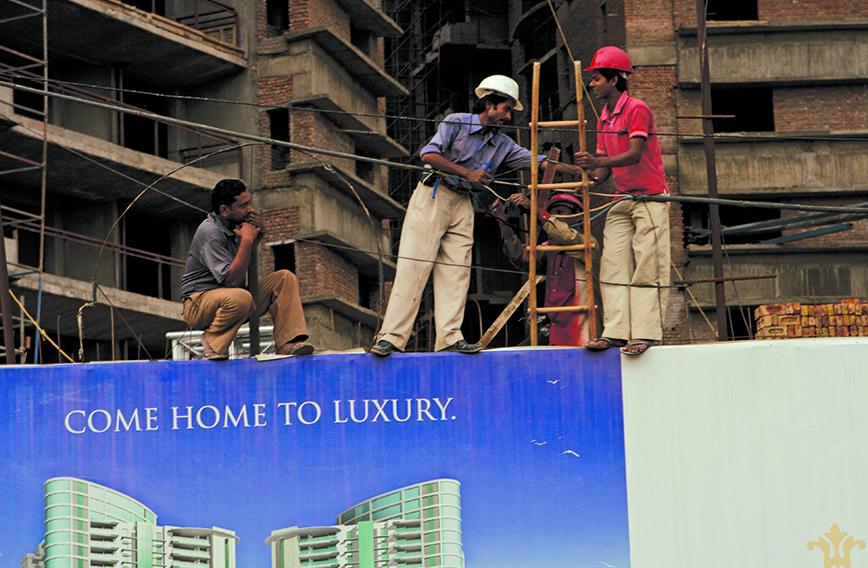

Labour continues to be underpaid and work conditions are perilous

Informal work has been growing and is as nasty

Rajiv Khandelwal

TWENTY years ago, the idea of establishing Aajeevika Bureau took seed in our minds. We were excited about the possibility of sparking lasting impact on the lives of millions of informal, especially migrant, workers. We were cognizant of the harsh realities of the problems confronting workers. Our early travels to exploding cities and rapidly growing industrial markets in neighbouring Gujarat brought to us the harrowing conditions confronting thousands of workers from everywhere in the country.

TWENTY years ago, the idea of establishing Aajeevika Bureau took seed in our minds. We were excited about the possibility of sparking lasting impact on the lives of millions of informal, especially migrant, workers. We were cognizant of the harsh realities of the problems confronting workers. Our early travels to exploding cities and rapidly growing industrial markets in neighbouring Gujarat brought to us the harrowing conditions confronting thousands of workers from everywhere in the country.

These were workers migrating due to persistent poverty at home. They accepted work in Gujarat for meagre wages and in high-risk and hazardous conditions. No one had any written documentation of employment or a formal contract. Provident Fund, ESIC (Employees’ State Insurance Corporation) cover or social security of any kind was almost entirely missing.

If accidents or illnesses happened — and they did frequently — workers headed home rather than attempting to navigate or avail of health services in cities. Workers on construction sites and in hotels and factories had been herded by contractors. Few, if any, had any inkling of who owned their site or the factory where they spent most of their working day.

Communication was tedious. Only the contractors or supervisors had cell phones, if at all. Workers remained largely unconnected with one another and with their families at home. Only a few had phones in their pockets and they could barely afford to recharge their SIM cards. Banks would routinely refuse to open bank accounts as proof of residence or introducers were unavailable.

Wage payments happened in cash. Wage frauds and leakages went without redress. Workers rarely kept records of their attendance. There was no written history of payments. Many workers, especially Adivasi ones, lived life on the cusp of survival and destitution. Chronic debt, severe malnutrition and illnesses marred their lives back home and these issues travelled with them to cities where they worked.

The dense and decrepit neighbourhoods in which they stayed were largely beyond municipal gaze. Congested chawls with dark, dank rooms shared by male migrant workers became dens of disease. Workers whose rural homes were a day or overnight journey away, fled back home regularly, with frequent breaks from work. The work and living conditions were too arduous to be suffered for long periods — rest, recuperation and immersive social engagements were needed. In one of our early surveys, we noted that the Adivasi males exited their jobs in cities permanently at the young age of 32 years — as wages remained stagnant, frequent illnesses disrupted work and many faced abuse and bondage at the hands of their contractors and employers. Twenty years later, many of these scenes continue to replay.

STAGGERING NUMBERS

Despite a massive increase in the workforce over two decades, the share of informal employment in total employment continues to be staggering. In the past 20 years it has witnessed a minor decline — from 93.2 percent in 2004-05 to 90.6 percent today. Even in the formal sector, informal employment has jumped from 4.2 percent to 9.5 percent in this 20-year period.

No wonder 63 percent of India’s entire workforce does not possess a work contract. Nearly 54 percent works without any form of social security. And nearly 47 percent of the entire Indian workforce does not enjoy a single day of paid leave. A 10-to-12-hour gruelling, high-risk work shift has become normal for many engaged in informal arrangements.

Wages across the board for informal sector workers remain nearly stagnant or record meagre increments that lag far behind the consumer price index.

Work continues to be perilous for Indian workers. Work sites in India are amongst the most dangerous in the world. Even official estimates — which are severely under-reported — provide alarming evidence of workplace hazards. In 2021, the Union labour ministry informed Parliament that at least 6,500 workers died on duty in factories, ports, mines, and construction sites in the preceding five years. Over 80 percent of these fatalities were reported in factories. In fact, deaths in factories increased by 20 percent between 2017 and 2018.

Most of these deaths were reported from the top industrialized states, including Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu. Let us not forget that for every death that occurs, there are multiple cases of grievous injuries and accidents that happen and that bring life-long disability to workers.

DILUTION OF SAFETY LAWS

Undoubtedly, the rising graph of industrial accidents is strongly correlated to the dilution of industrial labour and safety regulations everywhere. It is also strongly linked to another reality — the fragmenting of industrial production where manufacturing, processing, assembling, grading, recycling work gets outsourced to smaller sites and units. For smaller players, investments in workers’ training, safety infrastructure or an ecosystem of prevention are too remote (and possibly too expensive) to be implemented.

Since the initiation of India’s industrial era was led by the public sector, the discipline of occupational health and safety became embedded in large factory units and sites. This has yet to find its way to millions of smaller enterprises and units where downstream manufacturing occurs and where workers are exposed to utmost risk. For all the modern advances in India’s celebrated industrial clusters, the industry supply chains and their workers largely sweat it out in an era reminiscent of medieval times.

New forms of work and work arrangements have also emerged, probably unimagined two decades ago. Many of these are driven by advances in digital technology which has given impetus to a massive increase in e-commerce and the advent of app-based services and work.

Gig work has redefined the standard notion of work and the core employer-worker relationship. It is creating a large underclass of workers who are unable to claim stable wages or social security and whose incomes are tied to complex algorithms that push workers unsustainably harder to earn a decent return. Legislation to govern work and the work conditions of these workers is still in the early stages of being formulated.

In the labour markets familiar to us, we’ve also been witness to other technology-related shifts that overburden workers by significantly increasing and expanding their load. One of the most telling examples of this shift is in the colossal power loom clusters where hundreds of thousands of migrants find work. New and rapid machines have reduced the demand for workers on the shopfloor. However, machines now allotted to workers have increased in number, making shifts longer and more exhausting and their earnings more volatile.

COVID AND BEYOND

It took the Covid pandemic for the migrant experience to find its voice. The sheer magnitude of misery inflicted on migrant workers trapped in unfriendly cities and their treacherous journeys back home elicited sympathy for their fragile condition. Much was said about the need to create databases of migrants and track them, provide affordable housing, create a portable Public Distribution System (PDS), improve services for their stability and stand by their rights as citizens. But except for some new and local initiatives, much of the migrant discourse seems to have faded away.

At the national level the e-Shram programme to register all workers has resulted in workers being logged. However, registration is unlikely to result in any shift in the informality that corrodes workers and work conditions. For this, stronger labour governance and laws are needed, not less. Not just for the migrant worker community but for workers at large. The gaze of labour rights has firmly shifted to the smokescreen of massive welfare schemes for workers. In this single-minded pursuit of registration, enrolment (usually digital) and seeking schematic benefits, the core attention to wages and work conditions has been considerably diluted.

Over the past two decades, new migration streams have etched their routes on the labour mobility map. Transportation and communication infrastructure has made it infinitely quicker for workers to move from one part of the country to another. Climate induced distress in rural areas is pushing out larger numbers to look for survival farther from their regions. There is a rising number of women entering the migrant workforce even from societies such as Rajasthan where social orthodoxy inhibits women’s mobility. Long distances, long-duration migration among women is a sure sign of regions nearing destitution — the push of poverty is too severe for women to remain at home. Women’s entry into the workforce as migrants poses new challenges of ensuring security and parity with male workers. Even more important is the onerous task of reducing the burden of care duties among women, as they attempt to find dignified work.

As earlier, Dalits and Adivasis continue to be the most significant proportion of low-waged, unskilled, hazard-prone and casualized workers across all sectors. Social hierarchies and exclusions are routinely and brutally reproduced at work. This is unlikely to change within the foreseeable future.

INDICATORS OF CHANGE

Yet there are many strong signs of hope. We find a new sense of political consciousness and awareness of rights among migrant communities. This is encouragingly true among otherwise reticent Adivasi workers who are asserting their rights, seeking entitlements and are not fearful of fighting frauds of wage and compensation. We have an astounding traffic of wage disputes being registered across the country by workers who will no longer make peace with reconciliatory settlements by their employers. Encouragingly, women workers have begun to approach legal assistance directly as well.

Our advocacy with governments that calls on them to be a more forceful regulator and enforcer of labour rights does not usually go very far. We have, however, begun to see some signs of hope for responsible change in business practices that affect workers’ rights. This consciousness is rising on account of the concept of ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) and initiatives like Social Compact that are invoking, not moral responsibility, but an imperative of common cause among workers, employers and the economy.

Rajiv Khandelwal is co-founder of the Aajeevika Bureau.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!