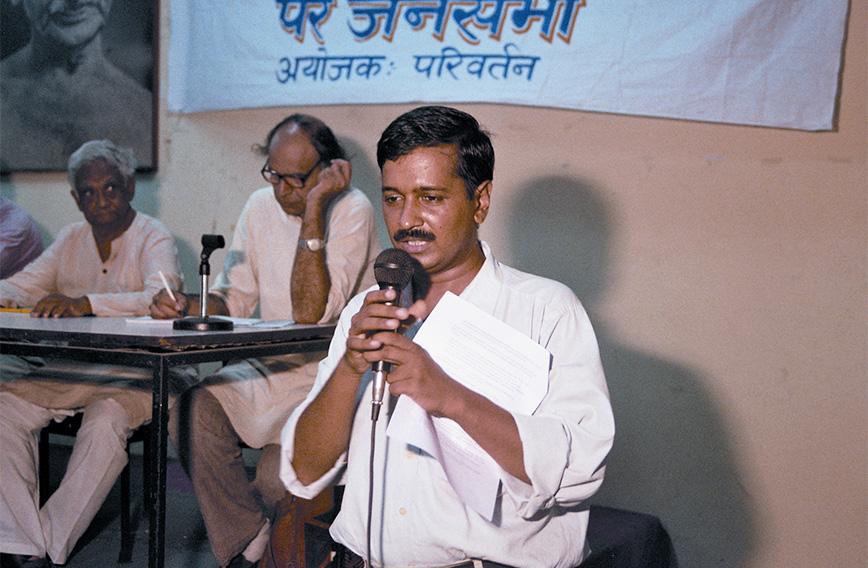

Arvind Kejriwal while working with Parivartan

Kejriwal writes

Arvind Kejriwal

Arvind Kejriwal wrote a column called 'Right to Know' for Civil Society from June 2004 to 2006. He was then running Parivartan, an NGO. The columns appear below.

The system sponsors corruption

June 2004

An aspirant for a licence for running a Kerosene Oil Depot has to appear before a panel of senior officials of the Food Department for an interview. One friendly kerosene dealer told us that he was asked in his interview how he would run his shop with very low commissions given by the government. The kerosene dealer replied, "Jaise sab chalate hain, waise hi main bhi chala loonga (I will also run it just like everyone else )." And he got the licence.

Corruption in our country is not only an outcome of degeneration of moral values. Often, it is the result of the existence of such systems, within which one cannot operate honestly and is forced to indulge in corrupt practices. The whole world knows that there are systemic faults, which are forcing the players to indulge in large-scale corruption. Those in power also know where exactly the problem lies. Yet, no action is taken to rectify the anomalies.

The Public Distribution System is a classic case of large-scale defalcation of food supplies taking place with everyone's knowledge. A kerosene oil depot (KOD) owner gets a commission of seven paise per litre of kerosene sold. The average quota of a KOD is about 10,000 litres per month. Hence, if a KOD owner works honestly, he would get Rs 700 as commission every month! Out of this amount, he has to pay rent, salaries, electricity, phone etc. He cannot make a profit if he works honestly. But the commodity he is dealing in generates huge profits for him if he diverts it to the black market. A KOD owner is required to sell kerosene at Rs 9 per litre compared to the market price of Rs 18 per litre. Thus, he has huge incentive to divert supplies.

Not that the authorities are not aware of these anomalies. Parivartan met an erstwhile food commissioner with a complaint of black marketing against a kerosene dealer. We wanted his licence to be cancelled because this dealer would not give any kerosene to holders of ration cards and would siphon off almost the entire stock. But the sympathies of the food commissioner were with the kerosene dealer. "You should not go overboard in your demands. They get such low commissions. They are forced to do all this. But I agree that everything should be done within limits." We were aghast to have to hear this argument. And do you know who has the powers to raise the commission of these dealers? It is the food commissioner himself. But still he would not do that.

The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) has prescribed rates for each type of work it undertakes. These rates were set in 1997. Now, bids submitted to the MCD have to state how much below or above the prescribed rate they are. Using the Delhi Right to Information Act, Parivartan sought copies of contracts of all the civil works done by MCD in two resettlement colonies in East Delhi during the period 2000-2002. When we took a look at these contracts, we were surprised to learn that in most of the cases, the contractors had bid to carry out works at rates much lower than 1997 rates. This was simply impossible. If we took inflation into account, logically, a contractor should have bid for at least 20% above the scheduled rates. But it is impossible to imagine how a contractor would work at rates 40% below 1997 rates. An assistant engineer told us that in such cases the contractor and the concerned engineers know that no work would actually be carried out and the money would be shared among them.

Parivartan verified all these contracts and found that in 68 contracts worth Rs 1.3 crores, work worth Rs 70 lakhs had not been done though payments had been made. A detailed report was presented to the Chief Minister, Chief Secretary, MCD Commissioner and Delhi Police to investigate and book the culprits. When confronted by a journalist after a few months as to what action he had taken on that report, the MCD Commissioner said, "Parivartan is not aware of the ground realities. They should understand the problems of the contractors. The contractors have to under bid so much to get any work that it is almost impossible for them to do a proper work at those rates." Such a statement on camera by the Commissioner was shocking. If the MCD Commissioner cannot take steps to rectify this position then who will?

Both the officers mentioned above are known for their integrity. Yet, just look at their willingness to justify a bad system. Is it because every bureaucrat inherently becomes a statusquoist?

The law works, Triveni and Nannu will tell you how they got their rations

July 2004

Right to information is redefining relationships between the government and citizens. Triveni is a matriculate. She was shocked to discover that her ration shopkeeper was siphoning off rations meant for her by making false thumb impressions on cash memos in her name. Actually, she didn’t receive any grains for six months. Whenever she would go to the shop, it would either be closed or the shopkeeper would say that there was no stock.

Triveni is a poor woman, who lives in a slum colony in East Delhi. She holds an Antyodaya card issued by the government to the poorest of the poor. However, it isn’t easy to get ration from a ration shop. In February 2003, Triveni filed an application under the Right to Information Act asking for the quantity of ration issued to her as per records and also copies of cash memos purported to have been issued to her. After a month, she received a reply stating that she had been issued 25 kg of wheat at Rs 2 per kg and 10 kg of rice at Rs 3 per kg very month in the previous three months. The cash memos showed thumb impressions having been made in her name. She is a literate woman and always signs. Naturally, the thumb impressions do not belong to her.

This shows that the shopkeeper had been diverting her ration by faking thumb impressions in her name. Triveni was shocked. But now she was equipped with evidence to proceed against the shopkeeper. But before she could take any action, the shopkeeper came to her house and pleaded with her not to take any action and that he would mend his ways in future. Since then, for the past year and a half, Triveni has been getting the right amount of ration at the right price.

Nannu is a daily wage earner. He lives in the Welcome Mazdoor Colony, another slum habitation in East Delhi. He lost his ration card and applied for a duplicate one in January this year. He made several rounds of the local Food & Civil Supplies office for the next three months. But the clerks and officials would not even look at him, leave alone attend to him or bother to tell him the status of his application. Ultimately, he filed an application under the Right to Information Act asking for the daily progress made on his application, names of the officials who were supposed to act on his application and what action would be taken against these officials. Within a week of filing application under Right to Information Act, he was visited by an inspector from the Food Department, who informed him that the card had been made and he could collect it from the office. When Nannu went to collect his card next day, he was given a very warm treatment by the Food & Supply Officer (FSO), who is the head of a Circle. The FSO offered him tea and requested him to withdraw his application under Right to Information, since his work had already been done.

These two incidents are not exceptions. They are daily occurrences in different parts of Delhi since the Right to Information Act was passed. Right to Information is redefining relationships between the government and citizens.

Ordinarily, what are the options before poor people like Triveni and Nannu? They could have complained to government officials. But no one would have listened to Nannu. No one would have listened to Triveni either.

There are no effective systems within governance, which hold government officials accountable. The officials know very well that nothing can happen to them. The chances of their inefficiency and corruption being detected and questioned are almost negligible. Hence, they thrive. Mr N Vittal, former CVC, once remarked that corruption is a business for corrupt government officials. The risks involved in this business are very low. If we have to make any dent, we would need to increase these risks.

Through the use of Right to Information, a powerless and poor person like Triveni suddenly gets equipped with evidence against the ration shopkeeper and the power equations between Triveni and the shopkeeper alter dramatically. If she wished, Triveni could have had the shopkeeper’s license cancelled. When Nannu asks for the daily progress report made on his application, the Department ends up admitting its officials’ inefficiency on paper. Nannu is asking them to furnish the names of the officials responsible for not doing his job forcing the Department to fix responsibility. Now, the chances of action against guilty officials or vested interests increase substantially.

This is precisely what the right to information does. The evidence of corruption and inefficiency, which was hitherto buried under red tape, comes under public scrutiny.

Let legislators be legislators

August 2004

One of my friends asked me the other day, “How is the new MP of your area? Do you think he will deliver?” For a moment, that set me thinking. What is an MP or an MLA supposed to do? What are his duties and what powers does he have?

The Constitution lays down distinct roles for the Legislature and the Executive. The Executive is supposed to run day to day governance. The legislature performs two important functions. It is supposed to make good laws. It is also supposed to keep a check on the executive. As a member of the Legislature, an MP or an MLA is to ensure that the government is run in accordance with the laws by asking questions in the Legislature, by actively and intelligently participating in debates within Legislature and by holding the Executive accountable through various Legislative Committees, of which he is a part. This is what the Constitution wanted a Legislator to do.

But suppose legislators started running the government. Then who would keep a check on them? The last decade or so has seen more and more Executive powers being conferred upon the legislators. The Constituency Development Fund is one such example. Every legislator gets roughly Rs 2 crores (for MLAs, it varies from state to state) every year to spend on the development of his constituency. In the state of Meghalaya, the MLA even issues letters to the contractors awarding them works, which have to be carried out of these funds. In Delhi, the MLAs are required to draw up the lists of beneficiaries of old age pension and widow pension. A number of legislators are co-opted in the Executive by making them members or chairpersons of various Boards or government companies.

In normal situation, any wrong work done by the government would be questioned in the Legislature. But glaring discrepancies brought to the notice of the nation in the use of constituency development fund by the CAG year after year do not cause any flutter in Legislature because the legislators themselves are at fault. Transparency International India, C. M. Michael from Meghalaya and several others have filed PILs in Supreme Court for scrapping of Constituency Development Fund scheme precisely for these reasons.

Recent times have seen an increasing trend of co-option of legislators into Executive. This trend has dangerous ramifications as it breaks down the internal checks and balances envisaged in the constitution. Parivartan sought lists of beneficiaries of old age pension and widow pension under the Delhi Right to Information Act for a small area in Delhi and found several discrepancies including bogus entities etc.

When action was demanded, we were told that no official is guilty as the lists were drawn up by the local MLA. Whom do you complain against the MLA? In Delhi, even the forms for these pensions are available only with the MLAs. The personal staff of some of the MLAs sell these forms, when the forms are supposed to be available free. Further, the forms are given only to their party supporters. Where do you complain? The normal vigilance machinery has no powers to proceed against legislators. Since the legislators themselves are indulging in these practices, the issue will never be raised in the Legislature.

A common citizen also needs to understand the role of a legislator. People rush to their elected representative whenever there is any problem in their area, including water, sanitation, electricity etc. A legislator is expected to provide solution to every problem. He is expected to call up the local government officials and order them to rectify the problem.

But that is not the role of a legislator. By doing this, a legislator directly interferes in the day to day functioning of the Executive, which he is not supposed to do. And by rushing to our local elected representative for every such problem, we are encouraging this trend. The people are expected to approach the local officials for redressal of their problems.

If they do not get a solution, then the elected representative is expected to either raise the issue in Legislature or seek a solution from the concerned Minister. However, I do not think any legislator follows this process.

The day to day interference of the legislators in the functioning of the local officials has become so rampant that it is commonly perceived to be their legitimate role. If any legislator refuses to do that, he is taken to be an insensitive and inefficient person.

But all this makes the role of a legislator quite unglamorous and dry. Following the above process would also need a lot of patience and understanding of constitution and democratic processes. How many of the present day legislators would qualify that?

Strong Lokayukta is the best answer

September 2004

Where does a common man report corruption in this country?

The role of people in our anti-corruption efforts has been largely neglected. All our vigilance and investigative agencies put together cannot match the information that the people have on corruption. With an efficient Right to Information Law in place, people can even dig out unimpeachable evidence. But where do they report corruption?

A road in Pandav Nagar in East Delhi was in a very bad condition. Residents of Pandav Nagar used the Delhi Right to Information Act to know when was it repaired in the last three years. They got a rude shock when they were told that the road was last repaired about a month back and had been repaired almost seven times in the last three years. This was a fraud because the road had not been repaired for the last several years. The stock register showed material having been issued from time to time for the "repair" of this road.

The people complained to the Deputy Commissioner of that area, CBI, and several other vigilance and anti-corruption agencies. But nothing happened to anyone. Not even an inquiry was ordered. One of the most important reasons why corruption has grown is that it is almost impossible to get any action taken even if one has solid evidence. More than anyone else, the corrupt know this very well.

Parivartan obtained copies of all the works carried out by the MCD in two areas in Delhi and found a shocking state of affairs. Payments had been made for 29 electric motors. None of them were actually installed. Out of 29 hand pumps paid for, only 15 actually arrived. Sixty-eight contracts worth Rs 1.3 crores were examined. Items worth Rs 70 lakhs were found missing. This report was submitted to the Chief Minister, Chief Secretary, MCD Commissioner, CBI, anti-corruption branch of police and many other authorities. No action was taken against anyone in the next one and a half years. When Parivartan filed a PIL in Delhi High Court, MCD responded by saying that they had carried out their own enquiries into the allegations made by Parivartan and had found all allegations baseless. One of the judges remarked how could a thief be asked to do one's own enquiries? The Court directed Delhi Police to hold enquiries and file a chargesheet against guilty officials within six months.

But how many people and organisations can approach Delhi High Court? The distressing aspect is that the entire anti-corruption set up has failed to contain corruption on its own and when people report corruption, the entire machinery gets into action on how to hush up the enquiries.

There is a very strong need for a body, which is independent of the government, can be easily approached and which can investigate corruption and deliver judgements quickly.

The institution of Lokayukta was created precisely for this purpose. The Lokayukta is normally a retired judge of a High Court who can only be impeached through a motion of the Legislative Assembly. A candidate is chosen through a process of consultation involving the leader of the Opposition and the Chief Justice of the High Court. All this imparts a reasonable level of independence to this institution. The institution of Lokayukta was created to hold its own investigations on allegations of corruption received from the public against elected representatives, and in some states bureaucrats too. The Lokayukta is expected to fix responsibility and recommend penal action against the guilty.

But this institution has remained a non-starter in most of the 14 states where it exists, except in Karnataka. This is because the Lokayuktas have not been given necessary powers to fulfill their responsibilities. For instance, in the case of Delhi, the Lokayukta has the powers to investigate allegations of corruption against elected representatives only. The Act specifically debars him from entertaining any case against a bureaucrat. The corruption of elected representatives is so intrinsically linked to that of bureaucrats that it is impossible to investigate corruption against an elected representative without investigating against some associated bureaucrats. This has rendered the Delhi Lokayukta totally defunct. According to the figures provided by his Secretariat, the Delhi Lokayukta investigated just one case in the last five years after spending Rs 1.25 crores on its establishment.

Governments realise the potential of a strong and effective Lokayukta. Perhaps that is the reason why the Central Lokpal Bill, which was introduced in Parliament in late 60's, is still languishing.

Punish the guilty in Delhi

November 2004

The Food Commissioner of Delhi refuses to take any action against the ration shop owners found guilty of siphoning rations meant for the poor. And he is stubborn, brash, and arrogant about it. But can the public do something about it?

The Public Distribution System (PDS) seems to exist only in files in large parts of Delhi. A survey of about 182 poor families in Welcome Colony in East Delhi revealed that 93% of wheat and 97% of rice meant for them had been siphoned off in a particular month. Another survey of 46 families in R K Puram revealed that almost the entire rations meant for them are being misappropriated. The people of Ravidas Camp in Patparganj were told by the ration shop owner that the government had stopped sending rations. The people had not received any grains for the last several years. When the records of the shop owner, obtained under the Delhi Right to Information Act, were shown to them, they were shocked to see how rations meant for them were being diverted month after month.

The shop owners forge the signatures of the card- holders to divert their supplies. Almost every shop owner in Delhi is forging the signatures of almost every one of the card holders registered with him every month. Such is the quantum of evidence available if the government had the slightest desire to proceed against some of the shop owners and set an example. The state of records also indicates the active complicity of the food department officials. The stocks are not tallying and sales are shown to have been made to fictitious card- holders. Even routine inspections do not seem to be happening.

"Siphon off" or "misappropriation" are soft words to describe the state of affairs. It is daylight robbery. And that too of the most mean kind. The food meant for the poorest of the poor is being robbed by the shop owners in collusion with the Food Department officials.

And when the people obtain records under Right to Information Act, verify it with the field situation and then make complaints to the Food Commissioner with incontrovertible evidence, the Food Commissioner has the cheek to refuse action on such complaints.

And it is not just the food officials who are partners with the shop owners in this crime. Every arm of the State including the police actively supports them. Several complaints of forgery, black marketing and theft have been made by individual beneficiaries and various NGOs to the police so far, but the police refuse to even register a case.

The shop owners turned violent in a number of places in Delhi when their records were obtained and the information contained in them was disseminated. In Kalyanpuri, the local Pradhan, who is alleged to have been "purchased" by the shop owners, drew out a dagger to stop volunteers from doing any survey in that area. The shop owners of Nandnagari physically assaulted Parivartan workers in the office premises of the Food Department. The shop owners of Welcome colony physically assaulted women volunteers and burnt all the records when volunteers were disseminating the information contained in records. The self-styled Pradhan of R K Puram threatened of dire consequences if the workers did not stop their activities.

The issue here is not just rations. Such a situation exists in almost every sphere of governance. The powerful from all sections of society have united to save their own interests through illegal means. The battle lines are clearly drawn. On one hand are the exploiters, the vested interests or the powerful mafia, which are symbolised by ration shop owners in this case. They have successfully co-opted every arm of the state in their business. They continue their nefarious activities with strong assurance and support from the law enforcement agencies. These agencies, which had been employed to check and prevent unlawful activities, not only turn a blind eye but also resist and obstruct any kind of investigations against their "partners". The refusal of the Food Commissioner to proceed against any shop owner points towards that.

On the other hand there are the exploited - the poor, illiterate and hapless population. What are the options before the public? How does one break this nexus and force the law keepers to do their job and punish the guilty? Isn't it possible to take action against the officials who refuse to act in accordance with law and who refuse to punish law- breakers? Isn't it possible to punish such Food Commissioners, who defend the law- breakers so openly and blatantly?

Theoretically, it is. Section 217 of the Indian Penal Code says that if any officer of the government were to act against any person and if that officer does not do that in order to save that person, then that officer could be prosecuted and sentenced for a period not exceeding two years.

The first reading of this section raises so much hope. But there is a catch. Section 197 of Criminal Procedure Code says before starting to prosecute any officer, you have to obtain permission from the government. Do you think that the government (which means some brother officer of the guilty officer) will ever grant such permission if you ever approached the government? CBI has been either denied permission or the government just sat on their requests for long periods whenever such permissions were sought by them. Is it possible that such permissions would ever be granted to the common man?

I am told by a number of my lawyer friends, though I do not have any data to prove this, that Section 217 of IPC has been rarely used in the history of independent India, though there would have been several lakhs of instances which could be termed fit for its usage. The beauty of this piece of law is that it puts power in the hands of the people - to prosecute an officer who does not act in accordance with law.

So, should sec 197 of CrPC be removed and should it be made easy for a common man to prosecute any guilty officer? These laws were made during British times. The British Government did not want any of its officers to be tried by any native without the approval of the Queen.

There would still be merit in continuing with sec 197. Removal of this section would make government officials vulnerable to all sorts of cases and a government servant would have to spend most of his time defending himself in various courts of law.

However, there should be a fixed time limit within which the government should be required to either reject or permit prosecution of an officer. Inability of the government to take a decision within such time should be construed as an automatic permission. If the government rejects a request for such permission in any case, the people should have a right to appeal against such a rejection in a court of law.

Will Delhi Govt act on its law now?

February 2005

Santosh, a 20-year-old Parivartan worker, was attacked by an unidentified boy on 30 December with a blade when she was coming to the office from home in the morning. The upper part of her throat was slit, which had to be stitched. If it had been a centimeter below, it could have been fatal.

This is the second attack on Santosh within a fortnight by the ration shopkeepers, whose corruption she has been consistently exposing by seeking their records using the Right to Information Act. On 13 December also, two boys attacked her face with a blade. Her hair got cut but her face was saved. This is the sixth attack on Parivartan workers in the last year and a half by the ration dealers.

What did Santosh do that the shop-owners turned so violent? Every day, she helps poor women in Sundernagari, a slum colony in East Delhi, file complaints with the local Food office of the Delhi government when they do not get their rations properly. Sometimes, records of ration dealers are obtained using Right to Information and complaints are made on the basis of discrepancies detected. Discrepancies range from false entries made in distribution records to forged signatures on cash memos. More than a 100 complaints have been filed in the last few months. And at the end of every month, Santosh uses the right to information law to know the action taken on complaints.

The Essential Commodities Act requires that a shop-owner should be prosecuted for each of these offences. The punishment ranges from three months to seven years of sentence. Strong punishment is provided in Indian Penal Code too for some of these offences. In the case of PUCL vs UOI, the Supreme Court has directed that the licenses of such shops should be cancelled forthwith. The law, therefore, requires that local Food officials should suspend the shops immediately and register FIRs against them on receipt of such complaints. However, either no action is taken by the Food officials or at best, the shop-owners are let off with minor fines.

The complaints have proved to be a goldmine for the Food officials. A deal is struck to hush up each complaint. In one case, a shop-owner is believed to have paid about two lakh rupees to the Food officials to get one complaint against him scotched. In another case, a shopkeeper claimed having spent one lakh rupees. After taking the money, the shop-owners are told not to worry about any government action but to "take care" of Parivartan people, who keep nudging Food officials for action on complaintshence, the violence against Parivartan workers.

But the complaints had some positive impact. The cost of corruption became steep with the flood of complaints. As a result, the shop-owners started opening up shops. The people who had not received any rations for years started receiving their full quota. The ration dealers of Seemapuri told us that they have decided to give proper rations to everyone and not to give any opportunity to anyone to make a complaint.

The critical role in this drama was to be played by the "public servants". They did play a critical role but they acted against their masters. The people of this country pay through their nose and provide a comfortable living to these babus. The babus had the duty and the necessary powers to set the machinery right. They opted not to do so for purely selfish gains. Various surveys indicate that more than 90 percent of the rations are being siphoned off. Obviously, they are partners in the loot. As a result, the public has been suffering. When some citizens took initiatives to reform the system, these servants of the public created conditions to scotch these initiatives, even if it required violence. Simultaneously, they squeezed the ration dealers from all sides. In addition to regular hafta, they started extorting money from the ration dealers for settling complaints and providing protection against Parivartan. It needs to be understood very clearly that the real villains in this entire drama are these public servants. And their business is thriving because there is a total absence of any effective law under which they could be punished.

It is high time we had specific laws to hold them accountable and to punish them. Let the Government make certain basic commitments to the citizens of this country. Each Department should be asked to list down different types of interface that it has with the public. For each such interface, it should be clearly mentioned how and in what time would the work of a citizen be done. It should also be mentioned in how much time would complaints from the public be acted upon. These commitments should be non-negotiable. If any of these commitments are violated, the citizens should be able to appeal to an independent body like Lokayukta or a Public Grievance Commission (PGC). The PGC should have the powers to fix responsibility and impose penalties on the guilty officials within a fixed time frame for each case of violation.

When we approached the Delhi government after the attack on Santosh, a very senior authority remarked, "Jhanda utha kar chale ho to marna aur pitna to padega hi." (If you are fighting against injustice, be prepared to be beaten up). Are we fighting a foreign government? The governments cannot remain a mute spectator if the people exposing corruption are beaten up and murdered.

It was easy for the governments to enact Right to Information laws. It would need a very strong political will to take action on the corruption exposed through its usage. The governments would also need to provide strong support to the people who use right to information and expose corruption, as they would be increasingly attacked by the vested interests. Right to Information laws provide a unique opportunity to declare a war against corruption. It provides an opportunity to every citizen to participate in this war. If all right minded people, both within and outside the government, join hands in this war, I am sure we can together make India a better place to live.

Fighting corruption with Gandhi

March 2005

Mahatma Gandhi is still alive. his strategy of satyagraha still works. And it works better than any other method.

On Republic Day, a large number of people in Sundernagari, a resettlement colony in East Delhi, decided that they would forego their ration entitlements (wheat, rice and sugar) for one month in February to condemn the repeated violence on the people fighting against corruption in the Public Distribution System in Delhi and to express their solidarity.

In the last few months, there have been a series of violent attacks on people who had been exposing corruption in the distribution of rations to the poor people. The last attack took place on 30 December when the throat of a 20- year old girl in Sundernagari was slit by vested interests. Naturally, the people of Sundernagari were enraged. They wanted to protest. But the question was, how do they register their protest effectively? Should they take out a peaceful rally or should they sit on a day- long dharna? A series of meetings took place in Sundernagari in which this issue was discussed in detail. It was felt that a rally or a dharna of a few hundred people would hardly make a difference to the powers that be. The people said in these meetings that they wanted to take rations only if it were given to them with honesty and dignity. They did not want rations if it involved violence, corruption and abuses. It was also expressed in these meetings that the shops exist as long as the people take rations. The Food Department officials also exist so long as people take rations. If the people decided not to do so, neither would the shops exist nor would the jobs of Food officials. This thought gave that spark. It gave strength to the people. It was decided that the people should forego their ration entitlements for a month to express their solidarity and to condemn violence. It was a novel way of expressing protest, a gentleman's way, by undergoing self-sacrifice.

During Republic Day celebrations, speaker after speaker exhorted a gathering of about 700 people to forego their rations for a month. The decision was formalised and a letter sent to the Chief Minister of Delhi. And it had impact.

Since 1 February, almost unbelievable things are happening in Sundernagari. The Delhi Government is keeping a strict vigil on each of the shops. The Food Inspector is moving around with a video camera to record the movement in each shop. The Assistant Commissioner and the Food Officer are moving around to ensure that the shops are open and there is sufficient stock. The shops which used to open for just a few days in a month are opening daily (even during the lunch hour!). The supplies never used to arrive before the 25th of any month. This month, the supplies reached on the 1st day of February in all the shops. Earlier, the shopkeepers would abuse the poor people and cheat them, when they would go to the shops to take rations. The same shop owners are going to each house and pleading before the people to come and take rations. A daily report of the list of people who took rations in each shop is being prepared and pasted on a notice board outside respective shops. A copy of this report is also being sent to the top authorities in the Delhi Government.

Sundernagari has a population of almost a lakh of people out of which 9000 families possess ration cards. It is not that 100 percent of people in Sundernagari are foregoing rations. By the middle of February, as per government records, almost 2500 families had picked up their entitlements. But it should not be looked at as a game of numbers. It should not be looked at from the perspective of losses or victories. Such people, who wished to condemn violence, are doing so by foregoing their rations. The number of such people could be a few hundred or a few thousand. It would be cruel and unjust if we reduced it to an exercise in numbers. If a poor family is foregoing a month's ration, it is much more than a symbolic gesture. The sacrifice of each of these people needs to be recognised and appreciated. The reasons why they are doing this needs to be appreciated. And if things do not improve in future, this may be the first step to a more intense struggle.

A number of people had expressed fears that the rations that they forego might be siphoned off by unscrupulous elements. however, the Chief Minister assured that necessary arrangements would be made to allow people to inspect distribution records on the 5 March. The people will be able to see whether the rations foregone by them had been returned to the government.

Normally, the ration shop owners sell some rations to the regular card- holders and sell the rest in the black market by making false entries in their records. In the month of February, their illicit income is taking a severe beating because daily stock position and distribution records are being put up on the notice boards every day. They are unable to fudge entries this month because they know that their records would be thrown open for public inspection on 5 March. If any card-holder finds a wrong entry made in his name on that day, the shop could face cancellation and criminal charges. During February, the regular incomes of the shop owners has also taken a beating since a number of families are foregoing their entitlements.

This whole exercise raises some interesting questions. All this while, the people kept pleading with the government to provide them proper rations but the government claimed helplessness. The government forwarded complex theories on how there were serious systemic deficiencies and how the present system could not be made to work. But when the people declared their intentions to forego their rations, how did the same system suddenly start functioning? On receiving clear directions from his bosses, the local Assistant Commissioner came back to his area and simply directed all the shop owners that they had to deliver. And strangely, the shop owners followed his directions. Why is it that the shop owners suddenly decide to fall in line? Why is it that the same Assistant Commissioner was unable to tame shop owners earlier? This means that he has the necessary powers and resources to provide good governance. he did not have the intentions earlier.

This is true for all spheres of governance. Aren't the constraints talked about by the governments just excuses? The governments do have the capacity to provide clean and just governance. What lacks is its purity of intentions.

It also shows the people's power. That the people are not helpless. That the role of the people in making democracy work is critical and that when the people act, the vested interests run for cover. The people will have to tell the governments in an unambiguous and determined manner – "We want clean and just governance. If you can provide it with honesty and dignity, we will accept it. Else we do not want your services." This simple statement made with determination has the potential to shake the existence of the governments.

The big mess in Delhi’s water

June 2005

At the instance of the World Bank, the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) requested a consortium of consultants consisting of Price Waterhouse, DHV Consultants of Netherlands and TCE Consulting Engineers Ltd, to write a prescription for the ailing water sector in Delhi. This group of consultants has submitted a series of reports. The Delhi government has already started implementing their recommendations.

Solutions to Delhi's water shortages are closely linked to the working of DJB. The consultants have observed that it is in a financial mess and depends on a subsidy of Rs 350 crores a year from the Delhi Government.

DJB's poor finances, the consultants say, are the direct result of the extremely low tariffs that it charges for its water. They recommend a steep increase. According to them, the water sector should be run on commercial principles, like any business. Tariffs should be raised to a level so that DJB recovers the full cost of operation and maintenance, including depreciation and debt charges, in a phased manner. Presently, political considerations keep the government from raising tariffs. Therefore, the power to fix tariffs should be vested with an "independent" regulator who would be guided by purely economic considerations.

The consultants recommend that government subsidies should be phased out. But what would happen to DJB's finances if the subsidies were phased out? Where will the money come from? Even if the steep hike, as proposed by the consultants, were implemented, the annual cash flow projections for DJB for the next decade or so show that DJB's finances would continue to be in the red and keep mounting every year. To overcome this, the consultants recommend that annual cash "grants" be given by the Delhi Government to the water utility to meet the balance cash requirements. Rather than decreasing, the cash grants keep increasing every year and reach Rs 1045 crores by the year 2011. What is the difference between a subsidy and a cash grant? they want the Delhi Government to stop giving subsidy but start giving cash grants!

The consultants also want cross subsidies to be phased out. Presently, domestic consumers consume 87% of the water and contribute 48% of the total revenue, whereas industrial and commercial consumers use 13% of water and contribute 52% of the total revenue. The consultants consider this situation as unfair and want it to be rectified over a period of time. Hence, they recommend a very steep increase in prices of domestic water. The consultants have projected an increase by more than10 times in revenue from Rs 69 crores in 2002- 03 to Rs 725 crores in 2011-12 from domestic consumers. For the corresponding period, they have projected a three-fold increase in revenue from commercial consumers from Rs 38 crores to 107 crores. And an increase of just a little more than double from industrial consumers from Rs 22 crores to Rs 56 crores.

Why do the consultants have such a strong bias in favour of commercial and industrial consumers? the consultants have not given any convincing explanation why they want the cross-subsidies to be removed. If better profits are available to DJB from the commercial and industrial sectors, why should it forgo this advantage? It does not seem to make business sense. And since water is essential for human survival, the first right over water should belong to individual human beings for drinking and other purposes. Commercial and industrial purposes should have last right over water. They should, therefore pay much more than individuals.

In Delhi, water charges include sewerage charges. Now, the cost of collecting, conveying and treating effluents is much more than that of treating and distributing water. The consultants admit that commercial and industrial users put a much greater burden on sewer system than the domestic users. Therefore, they should be made to pay much more. However, the consultants have not quantified the extra burden put by the commercial and industrial sector on the sewer system.

Interestingly, the consultants do not recommend any hike in water prices in the NDMC and cantonment areas. For NDMC areas, the revenue collections are projected to increase from Rs 17 crores in 2002-03 to Rs 18 crores in 2011-12. In the corresponding period, the revenue collections would increase from Rs 4.9 crores to Rs 5.3 crores in cantonment areas. This means that the people living in MCD areas would end up heavily subsidising the NDMC and cantonment areas. What is the reason for this bias in favour of the NDMC and cantonment areas? It seems that the consultants have not been guided by sound economics.

According to the consultants, the total cash requirements of DJB would be Rs 8669 crores in 2011-12. The water availability, net of losses, would be 3388 MLD. If we assume that by then subsidy and cross-subsidy were completely phased out as per the consultants' prescription, the cost of water would be Rs 71 per KL in 2011-12. This means that a middle class family of five with an average consumption of 30 KL of water would have to pay Rs 2100 per month against their present monthly bill of Rs 192. A family of five living in slums and consuming 6 KL of water would pay Rs 425 per month against their present monthly bill of Rs 75. The consultants say that tariff rationalisation will bring the following additional benefits:

- The wastage of water would be reduced.

- People in water surplus areas will use less water thus making water available for deficient areas.

The above two advantages seem theoretical and simplistic. There isn't evidence to show that the wastage of water by consumers is a significant issue in a water balance sheet. So, one is not sure if any significant savings in water would happen through tariffs going up. Besides, inequitable distribution of water has no relation to tariffs. It is either due to systemic problems or a conscious decision of DJB to supply more water to certain areas than to the others. Against an average 100 litres available to a person per day in the MCD area, 400 litres of water is available to a person living in the NDMC area. If the consultants were serious about stopping wastage and checking inequitable distribution of water through tariff, they should have increased tariffs for NDMC areas rather than MCD areas.

Let us see who gains and who loses from these prescriptions. Industrialists and shopkeepers, all across Delhi, gain in terms of lower water tariffs. The people living in NDMC and cantonment areas gain similarly. But 93% of the population living in MCD areas lose tremendously. Their water tariffs are likely to skyrocket to a level where water just might become unaffordable, not only for the poor, but even for the middle class.

Do these steps benefit the government? the government would continue to dole out huge amounts every year, as it is doing at the moment. Presently, the element of cross-subsidy reduces the government burden. Removal of crosssubsidies is likely to further increase the government commitment from the Rs 350 crores subsidy at present to Rs 1045 crores as "cash grants" and Rs 2310 as loans by 2011. This is projected to keep increasing thereafter. So, the government will continue to bleed.

So, what exactly do the consultants hope to achieve? To my mind this seems an elaborate exercise not to improve water services in Delhi but maximise the profits of the private companies that will finally takeover from DJB.

Delhi’s murky water plans

July 2005

At the instance of the World Bank, the Delhi Government is handing over the operations and maintenance of two zones of the Delhi Jal Board DJB) to companies under management contracts.

The zones are South II (S II) and South III (S III), which include both poor and middle class areas. The contracts will be for six years initially. The companies to which the contracts are awarded will be responsible for the day-to-day running of the entire gamut of services relating to water supply: distribution, collection of revenues, addressing consumer complaints etc.

Two years after these contracts, DJB's operations elsewhere in Delhi would similarly be handed over to other companies. Presently, most of the areas in these two zones receive less than four hours of water supply every day. Water pressure in many areas is so low that people have to install booster pumps. Repeated complaints to DJB yield no results.

The private companies are expected to put such systems in place that there will be continuous water supply to each person living in these areas 24 hours a day seven days a week. These companies will also be expected to provide efficient complaint handling systems.

The zones South II and South III have middle class areas that include Kotla Mubarakpur, Defence Colony, Dayanand Colony, Jangpura, Bhogal, Okhla, Sriniwaspuri, GK, Girinagar, Nizamuddin, Malviya Nagar, Gulmohar Park, Saket, Madan Gir, Tughlakabad, harkesh Nagar, Dakshinpuri, Madangir, Green Park, hauz Khas, Dr Ambedkar Nagar and Sangam Vihar. Poor areas include several slums, resettlement colonies and urban villages.

GKW, a consultancy firm, has provided a road map for the distribution of water by private companies.

The promise of 24X7 : Where will the water come from?

Let us see whether there is enough water available to provide it all day seven days a week. According to GKW, if continuous water were to be provided to S II areas, 226 MLD of water would be required in the first year. Subsequently, the private company would take steps to reduce leakages and reduce requirement to 190 MLD by the end of three years. even after this, there would be a substantial gap between water demand and supply. Similarly, if continuous water were to be provided to S III areas, 180 MLD of water would be required in the first year. This requirement would reduce to 150 MLD by the end of three years.

Where would the additional water come from? GKW says it is DJB's responsibility to provide additional water! If DJB provides this much water to S II and S III, then the private company will be able to provide universal 24X7 supply.

Where will DJB get this water from?

There is no clear answer. It was expected that the Sonia Vihar water treatment plant would become operational by the time these management contracts were given out. It was planned that these zones would then be provided all the water necessary to enable the private companies to provide water 24X7.

But the Sonia Vihar plant is not functioning as yet. So, will the water be diverted from other areas to these two zones to help new managers demonstrate their efficiency? The consultants say that "success" in these two zones would be showcased so that management of other zones can be similarly handed over to private players. But if success is achieved either by providing additional water from Sonia Vihar or by diverting supply meant for other parts of Delhi, then how could the credit for its success be given to the "efficiency" and "expertise" of the private firms who have taken over from DJB?

Is there a 24X7 water supply for poor people?

Water sector reforms hold out the promise to provide supply 24X7 to rich and poor alike. But there are no concrete suggestions as to how the poor will be served.

There are no water connections for 53,000 households living in slums in the S II zone. It is the same story in other poor localities. These areas do not have any distribution networks. Almost 265,000 people depend on unreliable and ad hoc supply from standposts, water tankers or through illegal tapping of water mains. Just about 10 litres of water is available per capita per day to these people, which isn't sufficient for even drinking and cooking purposes. Similarly, 14,000 poor households in S III are not a part of the regular water distribution network.

Water reforms envisage putting an end to the stealing of water from mains. Water supplied through tankers and standposts will be seen as non-revenue water (NRW). There will be annual targets for reducing NRW. Penalties are planned if these targets are not met. each bucket of water provided to the poor would increase NRW. So, all the "illegal" sources of water to these areas would be plugged without making corresponding legal arrangements for providing water to these areas. Forget 24X7, it is not clear how these areas will get any water at all after reforms.

The private company will have to pay a penalty to DJB if it fails to provide 24X7 water to people with regular water connections. Naturally, in the case of any shortfall etc, water would be diverted from poor areas to areas.

Why should these people remain permanently out of the mainstream? Why shouldn't the water distribution network be extended into these areas? Why shouldn't they also be provided regular water connections? Why shouldn't they also be a part of the proposed 24X7 systems?

Evaluation of private company on its promise of 24X7 supply

It is proposed that a penalty would be imposed on the private company if it fails to provide 24X7 water. Sounds good. But how does it work?

This performance is conditional to the DJB making a promised quantity of water available. Given the difficult water supply position in Delhi, DJB may not be in a position to fulfil this commitment most of the time, thus freeing the private company from his commitment of 24/7.

Even when the DJB supplies that much water, performance of the private company will be assessed not on the basis of whether you received 24X7 water in your house, but on the basis of whether the private company provided 24X7 water at the input point of each district metering area (DMA) or not. each zone is being planned to be divided into several DMAs. The DJB has to supply the required quantity of water at the input point of each zone. The private firm has to ensure 24X7 water supply at the input point of each DMA in that zone.

Thus, if you are not getting water for the last three months in your street due to some local fault, the manager could still be assessed to have provided water 24X7 in the entire zone and could still get his bonus for good performance as long as water is available at the input point of all DMAs.

Isn’t DJB paying out too much?

August 2005

The Delhi Jal Board has 21 zones. As part of a World Bank funded project, the management of each zone is being handed over to a foreign water company, which would operate and run it. As a result, it is not clear whether water would flow from taps or not, but money will certainly flow from the public's pockets to the coffers of private water companies. The contracts proposed to be signed between the water companies and DJB seem to be a financial bonanza for the companies.

Management fee: A fixed 'management fee' of about Rs 6 crores per annum would be paid for running each zone. This would go towards meeting the salaries of four experts at $24,400 per person per month. It comes to an additional expenditure of Rs 126 crores per annum for 21 zones for employing 84 'experts'. This is almost 20 percent of the existing O & M expenditure of DJB.

Bonus and Engineering consultancy fee: In addition, the water company would be paid a bonus, if it exceeded its targets. The company would also be paid an engineering consultancy fee every year to suggest what additional steps should be taken by the DJB next year to further improve services in that zone. Despite our repeated requests, we could not obtain the figures of the bonus and engineering consultancy fee proposed to be paid.

Annual operating budget - a blank cheque?: DJB is obliged to make an annual operating budget available to the water company to run the zone. The company would decide the amount of budget. No upper cap has been prescribed. This is almost like a blank cheque. The water company could also seek upward revision any number of times during the year. Internationally, it is seen that this is the most abused clause. In Puerto Rico, the operational expenses claimed by the water company (Vivendi) went up so high that PRASA's (the counterpart of DJB in Puerto Rico) operational deficit increased from $241.1 million in 1999 to $685 million in 2001. The Government Development Bank had to contribute emergency funding on multiple occasions. As a result, Vivendi had to go. It was replaced by Suez, which promised to cut losses by $250 million per annum. But as soon as they took over, they demanded an additional $93 million to run the water utility citing that "economic realities were very different from initial projections". Suez also had to go within two years.

Possibility of arm-twisting by water companies: Once they sign the contract, the water companies tend to blackmail and arm- twist the governments. They repeatedly approach governments with additional demands for funds. They threaten serious adverse impact on services if the demanded amounts were not made available to them. Water being a sensitive sector, it is not politically possible for the governments to ignore their demands or to even negotiate beyond a point. The governments end up obliging them most of the time.

Is it possible to improve DJB? Questions are being raised about the impact of the proposed project on water tariffs and whether there would be any concrete benefits flowing to the people. The DJB plans to give so much money and freedom to a water company to manage a zone. Presently, an executive engineer heads a DJB zone. Give all this to an executive engineer. Sign a performance MOU with him. Give him and his employees the management fee of Rs 6 crores (or much less than that). Give him the money and discretion to make capital investments. Give him the operating budget required. And insulate him from any interference. Give him absolute freedom to run his zone. Hold him accountable through terms and conditions specified in the MOU. He will run it at much less cost and maybe do a much better job. The DJB employees know the entire system in its minutest details. We never give the required freedom, powers and resources to our government employees and so we could never hold them accountable. The Delhi Metro is in the government sector but it is performing much better than any private sector, because Mr Sridharan enjoys the freedom and resources required to function.

Problem of governance: The present functioning of DJB leaves a lot to be desired. But it is not clear how handing over its management to private water companies would improve its functioning. It is basically a problem of governance. If a government cannot run a water utility because of its corruption and inefficiency, then such a weak government will never be able to 'regulate', 'control' or 'enforce' the private water company to abide by the rules. A private monopoly under such a weak and corrupt government is bound to play havoc on the public. We have already seen this happening in the power sector. So, the issue is not whether the water utility is in government or private hands. The real issue is whether we have an efficient, honest and strong government. Unless we have that, we will never get good services.

For democracy try panchayats

September 2005

A lot has been written on the deficiencies in our electoral system. That it involves huge amounts of money to fight an election. That it is almost impossible for an ordinary and good citizen to fight an election.

Theoretically, an MLA or an MP is a people's representative. But in reality, he is far off from the people. Most people do not even know who their elected representatives are. There is absolutely no mechanism whereby the people, whom he represents, can hold him accountable for his daily actions. The number of people that an MLA or an MP represents is so large that it is practically impossible for a significant number of his constituents to meet together at some platform regularly and discuss matters related to governance. So, once elected, he is totally unaccountable. People have that 'once in five year' tenuous and vague control over him when they can elect him out, if they were dissatisfied. But this control hardly provides any relief to a citizen in his daily life.

A lot has also been written on the party system. Today, the Congress is in power. Therefore, the BJP has to criticize them, irrespective of the merits of the issue. The converse would happen if the BJP were in power. Top bureaucrats are appointed largely on the basis of their political loyalties rather than their competence. Every little thing is looked at from the lens of party politics rather than from a national perspective. In Parliament, an MP votes on the basis of the party whip rather than his own judgement and conscience.

Is such a system inherently capable of delivering? Most people would say no, not because they have understood the system but because they are certainly disillusioned with its performance so far. The present political system does not offer any relief to a common man in his day- to- day life.

Is there a way out? Today power flows from the top to the bottom. This has to be reversed. It has also been seen that a good MLA or a good MP does not make much difference to the lives of people as much as good panchayats or good Resident Welfare Associations can. It has also been seen that people have much greater say and control over the affairs of their panchayats and RWAs than they have over their MLAs or MPs.

I suggest the following as food for thought. The party system should be abolished. Panchayats should form the core of polity. Direct elections should be held only to panchayats. There should be a panchayat for every two to three thousand voters. For urban areas, a Resident Welfare Association (RWA) could act as a panchayat. The Election Commission should conduct elections to both urban and rural panchayats. The panchayats should have the power to directly deal with most local issues. They should have complete powers to plan and spend all the money meant for that area. however, the panchayats would simply act as an executive to implement the decisions taken by the 'collective body' of voters of that area, which would meet regularly, say every two months.

The 'collective body' would decide which roads to make, which parks to develop, how to spend the money, what action should be taken against officials whose performance is questionable, how and which officials to reward, etc. The panchayats would simply implement the decisions taken by the collective body. The local bureaucracy would directly report to the panchayat and the 'collective body'. The ‘collective body’ should also have the power to recall any member of the panchayat, at any time during the tenure of five years, through a laid down process, for misconduct or non-performance.

Members of the Legislative Assembly would not be directly elected. Representatives of panchayats or a group of panchayats would form the Assembly. Any MLA would conduct himself in the Assembly, not on the basis of any party whip, but according to the directions received by him from the collective bodies of panchayats that he represents. There would be no opposition party, as understood today.

The composition of the opposition would change depending on the stand taken by Members on each issue. The issue would be important, not the party, which in any case would not exist. The State Assembly and the State Executive will have powers only on such subjects, which have trans-panchayat bearings. here too, the directions on what decisions to take and which issues to take up would come from the collective bodies of various panchayats. So, power would flow from bottom to top unlike what happens presently.

Likewise, the State Assemblies would elect the national Parliament. The Central Government would also function similarly. however, the Central Government could have some powers to deal with extra-ordinary circumstances related to various forms of external and internal aggression or to deal with inter-state relations.

Such a system has several benefits. It will cut down costs of elections substantially – both for the state and for those contesting elections. There would be direct elections only to the panchayats, and not to State Assemblies or the national Parliament. The people would be directly involved in setting the agenda of the Assembly and Parliament. The decisions would also be directly dictated by the people. Such a system would be directly accountable to the people on a day- to- day basis. Every action of the government would reflect the aspirations of the people. It will be a true democracy, where people will actually run the government. And elected representatives will think of the country rather than their party.

Open letter to Shekhar Gupta

November 2005

I had responded to Indian Express chief editor Shekhar Gupta's article on citizens' protests over the Delhi government's proposed water reforms. Mr Gupta did not acknowledge my response. I have therefore chosen to use my column to write an open letter to him.

Dear Shekhar Gupta,

In your article in the Indian Express titled, "Our poor little rich", you have written, "the Socialites of South Delhi are now asking for more. Several RWAs are threatening to stop paying their water bills unless the Delhi Government junks water reform."

First, allow me to correct you with a few simple facts. The campaign against Delhi's water sector "reforms" is not confined to the middle class. It cuts across all sections of society. In the last few weeks alone, there have been more than 10 rallies and protest meetings in various slum areas. In several of these meetings, the people demanded withdrawal of this project, else they would stop paying their water bills. More than 70 people from resettlement colonies met Sonia Gandhi in the second week of October and requested her to have this project withdrawn. All of these events were sent to the press for coverage. Unfortunately, none of them were reported. However, when residents of South Delhi protested, the media immediately took note. This does not mean that the movement against this water project is exclusive to the South Delhi-based middle class, but only reflects an apparent bias in the media.

There is an assumption in your article that this water campaign proposes perpetuation of previous subsidies. This is simply incorrect. We want the April water tariff hike to be redesigned, for several reasons: the recent tariff hike includes fixed charges, which violate basic principles of efficiency; this structure militates against fundamental principles of water conservation; this structure was determined by the World Bank and its consultants, to the total exclusion of the people of Delhi, to ensure guaranteed profits for water companies. All of these facts are supported by government documents, which we would be happy to share with you. All of us at the campaign admit that water tariffs before the recent hike were abnormally low and needed revision. However, tariff revision should have been worked out through public consultations and should have promoted efficiency and conservation. When the Government failed to do that, we carried out that exercise ourselves, though to a very limited extent. We have had quite a few public consultations on this issue in the past few months. These consultations have thrown up a tariff structure, which, while providing water to the poor at cheap rates, would also wipe out the losses of DJB without requiring any subsidies from the Government. In fact people want good services, not subsidies.

The Delhi Government is implementing a completely bizarre project in the name of "reforms". We are not alone in recognising this. After their own, independent analysis, 50 professors from IIMs and several engineers from IITs have written to the Delhi Government requesting withdrawal of this project. We have ourselves made detailed presentations to various officers of the Delhi Government, including the Chief Minister. But the Government refuses to listen. When the Governments become both deaf and dumb, what are the citizens supposed to do? In these circumstances, the people are resorting to non-payment of water bills to force the Government to listen to them, an action termed by you as "anarchy". You have written, "for the most privileged and prosperous section of Delhi's elite to refuse to pay their water bills is sheer anarchy and can be put down in 24 hours; just one night spent under a rickety fan in the police lock up would do."

Anarchy is the absence of order; this is not anarchy. On the contrary, governance on the whole is in anarchy. Government schools are in anarchy. Government hospitals are in anarchy. Government water systems are in anarchy. The decision of the Delhi Government to even consider implementing such a bizarre project is anarchy.

I offer myself, and many others do as well, to be put in police lock-up for the "crime" committed by us. I can only assure you - that won't stop us. We will continue with our demands. We will oppose this project steadfastly, until the very end.

When discussing such an important issue, we should not be dogmatic. Several people "believe" that if the State did everything, it would solve all our problems. Many others "believe" privatisation would solve all our problems. My old grandmother used to "believe" that Lord Shiva could solve all our problems. It is extremely important that we look at each problem separately and give ourselves the best possible structures and solutions specifically suited for that problem, rather than address issues superstitiously.

Clearly, we have a corrupt and inefficient Government. So, we decide to privatise the water utility, which is a natural monopoly. But we do not get the benefit of the "market" or "competition", which are necessary to hold the private sector accountable. In a competitive environment, the market decides the price and quality of services. In a monopoly, there is no market. So, we leave the responsibility of "regulating" the powerful and vested private sector in the hands of the same inefficient and corrupt Government. There is an inherent contradiction here. How would a Government incapable of replacing faulty meters, collecting bills or replacing leaking pipelines regulate the activities of complex commercial entities in the private sector be they the Tatas or Reliance or some foreign company?

Therefore, we have reached a stage when we need to address governance. We cannot skirt this issue any longer. If we had an efficient and honest government, we would get good water services whether they were in government hands or in private hands. But since we have bad governance, we will get bad water services irrespective of whether they are run by the government or by private companies.

Mr Gupta, I understand that you are a very busy man. Still, I would request you to kindly make time in your schedule to investigate the government's proposal that we are opposing. Should you convince us that we are wrong, we will withdraw our movement. Or if you are convinced, instead, then I am sure you would join us in declaring non-payment of your water bills to have this absurd project withdrawn.

Yours truly,

Arvind Kejriwal for Right to Water Campaign

For a more responsive DJB

January 2006

The Delhi Government has withdrawn its loan application to the World Bank. It has put its plans to privatise Delhi's water on hold. But now lies the real challenge. What do you do with the Delhi Jal Board, which is in a complete mess? We need to find answers to this question.

The Delhi Jal Board (DJB) was set up through the Delhi Jal Board Act in 1998, before which it was part of the Municipal corporation of Delhi (McD). DJB is responsible for providing drinking water and sewer facilities to 1.5 crore people. However, DJB has miserably failed despite the fact that there is surplus water available in Delhi and there are surplus water treatment and sewer treatment capacities. Large parts of Delhi get water ranging from a few minutes to a few hours every day and many times, the water is dirty. On the financial front, the Delhi Government has to provide Rs 350 crore annually to cover its losses.

With surplus capacities, why is it that the DJB cannot provide services? Because there are large-scale leakages of water and money. We know how much goes into the system. But no one knows what happens after that. And there are no effective institutional methods to seek accounts and hold someone responsible.

Imagine an executive engineer. He heads a zone. He is never asked to account for the water that entered his zone. that's the position of every officer from the Junior engineer to the chief executive Officer. Whether the DJB runs losses or makes profits, whether the people of Delhi get good water supply or not – it does not affect anyone's life at the DJB in any manner. So, why should they perform? Why should they try to improve the system? Why should they listen to the people? Isn't it a farcical system? And where do the people stand in this entire system? People do not have any role in the decision-making process. there are no formal platforms to consult people. People do not have any role in deciding expenditure plan – how much money should be spent where and on what; deciding expenditure priorities – which project should be done first; designing projects – the designs are often unrelated to the needs of the people; project implementation – whether a project was carried out well, as per people's needs and satisfaction. Often crores of rupees are spent on projects and schemes, which do not bring any benefits to the people. And sometimes, a little expenditure could solve the problems of thousands of people, but they are never implemented. For instance, Bhalaswa resettlement colony came up in the late nineties. the people were promised regular water supply. However, it does not exist till date. People have petitioned all officials and local elected representatives. But no one is willing to solve their problem. not that there is a shortage of funds. Just that solving their problem is no one's priority.

Officials are not accountable to the people because the people do not have any role in assessing the performance of the officials. Many officials ranked "outstanding" by their superiors would be termed "horrible" if people rated them.

Therefore, DJB is largely a political problem. the entire decision-making and its implementation are concentrated in the hands of some bureaucrats and technocrats to the complete exclusion of the people. What is the way out? transfer effective control over finances and officials directly to the people. How do we do that? Let there be one Water council in every zone, whose members would be elected directly by the people of that area. Roughly 2000 households could elect one member through an election to be conducted by the State election commission. the council would decide the expenditure plan of an area, expenditure priorities, broad outlines of projects and assess the performance of officials. no expenditure could be made in that zone without the approval of the council.

The people of that zone, through the council, would therefore decide how much to spend, where to spend and when to spend. For instance, the water representative from Bhalaswa can now get the necessary expenditure sanctioned in the council meeting to get water to his area.

The council would assess the performance of the officials on the basis of annual and monthly targets. the council will have the power to award punishments and incentives to the officials. In every council meeting, the executive engineer would be required to account for the money and water supplied to him. DJB had set aside Rs 1.8 crores per zone under the World Bank project to be awarded as bonus to the companies, if they exceeded their targets. this amount should be made available to the council to disburse as cash incentives to the employees who perform well.

What if the water representative did not listen to the people or did not even consult them, as most of the elected representatives do now? Some steps could prevent this eventuality. Anyone from the public should be able to attend council meetings. this would enable the people to witness their representative's performance. If dissatisfied, there should be a mechanism to call him back and replace him in the middle of his tenure. Also, the representative would take only such stands in a meeting as he is authorised by the people of that area. A week before every council meeting, there should be a compulsory General Body Meeting (GBM), which would advise representatives what stand to take on various agenda points and what additional points to raise.

What if the local MLA or some political party co-opts the representative? Let him be from any party. We have to see how to force him to act according to the people's wishes. If the people felt that their grievances were not getting resolved, they should themselves attend council meetings, watch their representative's performance and replace him if dissatisfied.

What if the number of proposals received at the council is much more than the money available to fund them? Rather than rejecting a proposal, the council will then have to discuss the urgency of each project and prioritize them. Perhaps some projects may need to be postponed for some time. However, our hunch is that there isn't a dearth of funds. Just that the money is not deployed rightly.

Further, ensure equitable distribution of water all over Delhi and bring transparency in water distribution. Water enters Delhi from various states every day. this water should be accurately measured, which is not happening at the moment due to faulty meters. this water is fed into various treatment plants. the water entering and leaving these plants should be accurately measured. From water treatment plants, water should be distributed to various zones in proportion to population, which is not happening at the moment. the Mehrauli zone gets 13 litres per capita per day (lpcd) of water against Rohini, which gets more than 350 lpcd, nDMc gets 450 lpcd and Delhi cantonment gets 550 lpcd. Water supplied to each zone should be accurately measured through bulk water meters. excess or shortage of water received on any day should be distributed equally amongst all zones. the meter readings of all the meters starting from the entrance to Delhi right up to the zonal level should be displayed on a website daily so that people know how much water entered Delhi and how much reached their zone. Such daily display of meter readings would create necessary public pressure to keep water distribution as equitable as possible.

RTI getting stuck with bureaucrats

April 2006

The Central Information Commission (CIC), set up by the Central government under the Right to Information Act 2005, has been facing criticism for its maladministration and lack of professional competence to handle the job at hand.

The Right to Information Act 2005 became effective on 13th October 2005. It is rightly being touted as one of the most significant legislations, post independence. Globally, the Indian Act is one of the most progressive amongst all right to information laws. It empowers every citizen to seek any information from any public authority, inspect any government documents, take copies thereof, inspect any government work and take samples of materials used in any government work.

If the information is not provided in 30 days, the applicant could appeal to the officer senior to the Public Information Officer (PIO), who was supposed to provide information in the first place. If the applicant is not satisfied with the order (or no order) of the senior officer, he/she could appeal to the CIC for Central government departments and the State Information Commission for the State departments. Information Commissions have to interpret the law and decide whether the information sought by the applicant should be provided or not. They have the powers to impose penalties up to Rs 25000, to be deducted from the salaries of guilty officials, for delay or malafide denial of information.