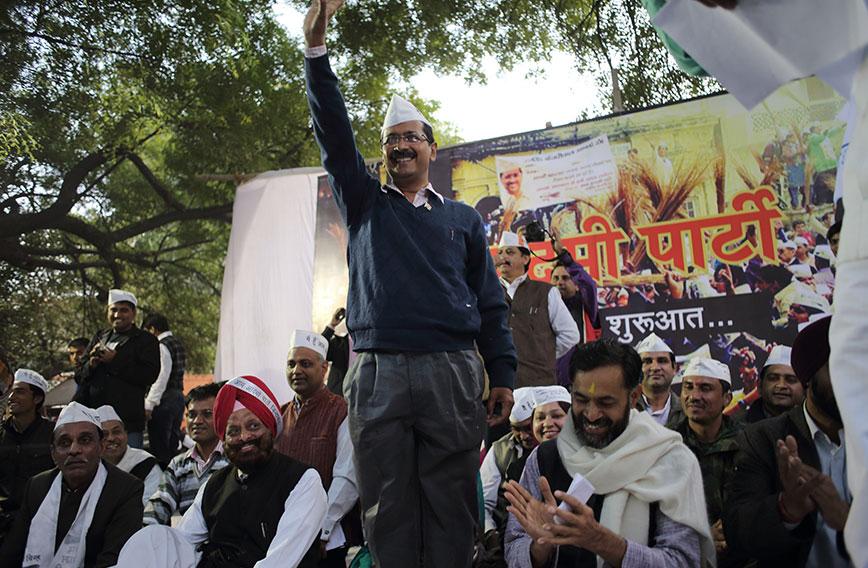

Arvind Kejriwal at AAP's victory rally

AAP and beyond: Broom as lightning rod

Civil Society News, New Delhi

This story appeared in Civil Society's January 2014 edition.

It was the day of counting and with the trends trickling in anonymous men and women, waving brooms, danced joyously in the street outside the office of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). As scenes go, the spontaneous cel- ebration told the story of the Delhi Assembly elections well. AAP’s gains, with its symbol of the humble broom held high, came from votes cast against both the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress, the two big parties.

In barely 16 months after it was launched, AAP had demolished the Congress and dented the BJP (by taking away two per cent of its votes) right in the heart of the Indian capital where money, influence and muscle power are known to hold sway.

It was an explosion of pent-up anger and resentment. For ordinary people, this was a victory over entrenched interests. The broom had served as the light- ning rod for their frustrations.

So, though in the final result the BJP got 32 seats, AAP 28 and the Congress eight, it was AAP that was really regarded as having won. When it did form the government, after some initial hesitation, there was in vast numbers of people unhappy with traditional politicians a sense of personal satisfaction.

Voters had sent out a significant message to the established parties and AAP’s success had proud owners among first-time candidates, volunteers and ordinary citizens with no previous taste of political involvement. They had all contributed and the impossible had happened.

Corruption, runaway inflation and collapsing urban services had sealed the Congress’ fate after three terms in office in Delhi. It was set to lose. But AAP’s audacious bid for power went beyond this. People saw in AAP an assertion of their own rights and an opportunity to shake a ruling elite obsessed with privi- leges.

In spirit, this was an uprising not unlike the one witnessed in Tahrir square in Cairo, with the difference that it was smaller, peaceful and within a democratic framework.

But barely had AAP begun enjoying its success when it found itself coping with the challenges of being in politics. Called upon to form the government, it shied away from the responsibility for two weeks. In a somewhat bizarre devel- opment, the AAP leadership decided to hold locality-level meetings and send out 2.5 million letters asking voters what to do. Voters were also told to sMs their advice.

Very quickly AAP began losing its newly earned goodwill. Questions began to be asked. Was it a movement or a political party or merely some kind of protest that had arrived on time to fill a vacuum?

To add to AAP’s stress, the Congress saw a Lokpal Bill through Parliament. A Lokpal, or ombudsman, to deal with corruption has been a key (some say the only) point on the agenda of the AAP leadership. But now the credit for creat- ing a Lokpal goes to the Congress and Rahul Gandhi and to the BJP, too, for sup- porting the Bill’s passage through Parliament.

Matters seemed to get stickier with Anna Hazare disowning AAP leaders like Arvind Kejriwal, indicating they had been opportunistic and manipulative in their politics. In the same breadth, Hazare welcomed the Congress’ Lokpal Bill.

Hazare, a crusader much feared in Maharashtra, had earlier been mentor to the AAP leaders. They had ridden to prominence on his shoulders during a national anti-corruption movement. His decision to disown them was embar- rassing and presented a moral challenge.

Delhi’s disparities

There are many ingredients in AAP’s election victory in Delhi. The city is the centre of political and administrative power. Those who corner influence and wealth think nothing of putting their status on display. For others, there are ris- ing incomes and aspirations. Migrants turn up here to earn more, but they don’t necessarily live better. The disparities in civic services are in fact stark. Even the middle class finds it tough to gain access to water, housing, schools, healthcare and transportation. The very poor have been picked up from slums and dumped in squalid resettlement colonies on the fringes.

Where reforms have worked, such as in electricity distribution, bills have shot up. Private power distributors are accused of inflating costs in underhand deals and burdening the consumer.

AAP has succeeded in being the timely voice of people struggling to cope with urban problems. The party has succeeded in resonating the anger of people. Its votes come from both the middle class and the poor because both were fed up of waiting for governance to improve.

At a victory rally held at Jantar Mantar a day after the results, emotions ran high. The slogan that truly defined the mood was the AAP cry: “Desh ka neta kaisa ho, aam aadmi jaisa ho! (What should a leader be like? He should be like an ordinary person.)”

Till well into the evening, Jantar Mantar overflowed with people who came from all over Delhi. They arrived by choice and when there wasn’t space on the road for any more of them, they climbed trees to get a view of the stage.

The AAP supporters were thrilled at having turned the tables on Delhi’s pow- erful. Loud cheers went up as the names of the winning AAP candidates were called out and their humble antecedents emphasised.

But the loudest approval was for the challenges thrown to the leaders of the Congress and the BJP.

“Let Arun Jaitley give up the comfort of the Rajya sabha and contest any Lok sabha seat in Delhi. We will take him on,” said Kumar Vishwas, one of AAP’s leaders. The crowd roared its approval.

Quick fix or solution?

AAP has clearly managed to strike a chord, but can it meet the expectations it has aroused? Is AAP a quick fix or a long-term solution? Have people found the answer to the problem of poor governance or is there a lot more churning com- ing up? The jury is out on such questions.

The challenge before AAP is to transform itself from a protest movement into a political party with vision and a long-term philosophy.

The anti-corruption agitation with Anna Hazare made headlines even if it delivered nothing substantial. It was certainly a wake-up call for politicians of all hues. A small band of agitators showed how they could rapidly build a big base of support on the issue of corruption and even force the mighty Central govern- ment into a corner.

similarly, the Delhi Assembly election was a David vs. Goliath encounter. The Congress and the BJP were too big to lose. But AAP, led by the redoubtable Kejriwal, changed the rules of engagement. The new party swamped social media and ensured it got coverage across newspapers and TV channels. It sent volunteers deep into neighbourhoods to take its message to voters in their homes.

AAP leaders and candidates were real – they could be touched and felt. They spoke a language people understood and raised concerns everyone easily shared. They were unlike the leaders of the established parties who were aloof and had forgotten what it is like to take a bus or walk on the street.

Competitive populism

But while AAP built its special identity by changing the rules of the game in multiple ways, the election promises it made laid it open to the charge of indulging in competitive populism. It offered all that the Congress has not been able to provide in three terms: good government schools and hospitals, free water supply, cheaper electricity, dependable public transport and safety for women.

The question is whether AAP can deliver on these counts or has the party put together an obvious laundry list to swing votes?

Dr Jayaprakash Narayan of the Lok satta party applauds AAP, but says he worries “about competitive populism at the cost of the long-term public good.” Lok satta was launched as a party in 2006 in Hyderabad because Narayan has

for long been a passionate advocate of clean politics and qualified people con- testing elections.

He says he needs to look much more closely at what AAP is promising the voters, but it is important to remember that the means are more important than the end.

“You have to curb your impulses,” explains Narayan, “because while you may improve the nature of the electoral process, I don’t think you will be able to improve the outcome in our country.”

He sees AAP as having scored high in dealing with money power and hered- itary power. But in the promises it is making to voters, there is the danger that it could be overreaching itself.

“That’s the tough thing,” Narayan says. “Lok satta has never yielded to that temptation. If anything, we spoke out quite vocally about (populist promis- es). I am sure they (the AAP leaders) will take a close look and review this.”

Narayan questions the wisdom of going back to the voters for approval on issues like forming a government or not. “I can appreciate the anxiety to involve people in decision-making, but beyond a small number, direct democracy does not work,” he says. “As a representative it is your job to lead people and not just give them what they want. Very often what people want is in the short term. As a leader it is your responsibility to think of the long term.”

Movement or party?

Dunu Roy of the Hazard Centre, which works closely with the urban poor, says it is unclear how AAP hopes to keep the promises it has made.

“I am not sure you can bring down the cost of electricity by 50 per cent unless you subsidise it. so I don’t know how they are going to do that. They say they are against privatisation, but they don’t say where the government will find the money to substitute private investment needed for economic growth,” says Roy.

“Whether it is housing, water supply, healthcare or education, AAP’s promis- es are not matched by strategies,” says Roy.

Roy believes that AAP has benefitted from the breakdown of governance in the country. “It has tapped into widespread disaffection with the Congress and in the process made promises it may not be able to keep,” says Roy.

Roy regards AAP as at best a protest against corruption, which has caught the attention of people. He wouldn’t give AAP the status of a movement because a movement is defined by a vision for the future. Nor can AAP be called a party, according to Roy, because it hasn’t formulated policies around the ideas it says it stands for.

Professor of sociology, Dipankar Gupta’s assessment is somewhat similar. “AAP is a good idea, but it is built on negativity, which is okay for this round, perhaps. It is a party meant for today, but I don’t know about tomorrow,” says Gupta, whose book, Revolution from Above: India’s Future and the Citizen Elite, has recently been published.

Gupta sees AAP as more of a movement than a party. “A movement by defi- nition is suicidal. It works towards its own annihilation when it is successful,” he says. “A party continues and this party has a strong movement element built into it.”

Gupta finds a lack of vision in AAP. “They are saying they will not be using cars with beacons, will not be corrupt. There is no health policy, no education policy – which the others also do not have.”

Gupta draws an interesting parallel between capitalism and democracy. “Whenever capitalism makes a breakthrough it is not out of sheer desire to make more money, but to see something new and adventurous happening,” he explains. “Likewise, in democracy, if you see the history of democracy, when things did change it was because people thought differently and that brought them votes. They didn’t think votes and then make those changes.”

Far-reaching change comes from the citizen elite or “citizens of calling,” says Gupta, because they can look beyond the needs of the present to aspirations of the future.

While liberty and equality are important, it is in fraternity and the strength- ening of citizenship that democracy thrives. societies that have made big leaps have invested in fraternity in the long term and created lasting foundations. A citizen elite has led the way.

AAP’s leadership seems to fail to qualify as “citizens of calling” because they prefer to mirror today’s realities rather than shape the future. In this respect AAP has shown itself to be no different to the other parties.

India’s big leap would come from a citizen elite with the vision to usher in universal healthcare, education, housing and so on from which will come a stronger economy. such a vision needs to go beyond the arithmetic of election victories and annual GDP growth figures.

Anupam Mishra of the Gandhi Peace Foundation is known for his documen- tation of traditional water systems in India. He has also worked among commu- nities at the grassroots and been a keen observer of movements.

“AAP must first of all understand why people have voted for it,” he says. “It shouldn’t confuse slogans with vision. You can’t run a government on slo- gans. Fighting corruption, for instance, is necessary, but it cannot be the basis for governance. In fact, sometimes corruption is the fuel that the sys- tem runs on.”

Mishra says water is an issue on which AAP could have shown it is a party of the future. Instead of promising people in Delhi free water, the party should have prepared them for the truth.

“It is not sustainable to bring water to Delhi from distant locations. What is needed is a culture of conservation and collection. Politicians who wish to make a difference need to lead people to such an orientation.”

The Delhi election verdict has raised hopes that politics can change. AAP has shown that people across professions are ready to be actively part of an election process.

AAP’s idea of consulting people through multiple referendums may not be entirely workable. But the fact is that mohalla sabhas or neighbourhood assem- blies have been held in large numbers across Delhi, fostering participation by ordinary people on a scale never witnessed before.

Prithvi Reddy of the AAP National Executive tells us in Bengaluru that AAP has 12,000 registered and engaged members. Asked if AAP can influ- ence an election in Karnataka, he says: “If I crunch the numbers it looks very achievable. In the past few Lok sabha elections in Bengaluru the winner has got about 350,000 votes or maybe 400,000 votes. This means we need about 1.2 million votes to win the election. simple math tells me that 12,000 volun- teers need to ensure that each gets the support of 100 people. We are saying get one vote for AAP per day. This then has a compounding effect and becomes a bigger movement.”

such confidence would have been difficult to come by earlier. so also the involvement of someone like Prithvi Reddy, who is an entrepreneur. There are innumerable others like him who have come out of the anti-corruption agita- tion. But whether they can seriously impact Indian politics and make AAP a party that prepares India for the future remains to be seen.

AAP’s candidates inspired trust

Civil Society profiled four new leaders with a difference

Surender Singh

Army cantonment

Surender singh is a busy man. After his win from Delhi Cantonment, every- one wants to talk to him. Dressed in military attire, he is holding rallies all over, thanking his voters and trying to address the problems in his area, one at a time.

He is no stranger to a jam-packed life. Having served the Indian Army for “14 years, 3 months and 10 days,” he has seen action in the Kargil war, Operation Parakram and Operation Black Thunder as an NsG commando during the 26/11 terror attacks in Mumbai.

Pointing to the hearing device on his right ear, singh says, “I lost my hear- ing in a grenade attack during the 26/11 operation. I didn’t get any proper medical attention.” For over 19 months, he had to run from one ministry offi- cial to the other in order to receive his pension. He believes dirty politics was at play behind this. “The ruling Congress party had to face the brunt of the public anger. The recent elections simply reflected that,” he says.

singh is one of the founding members of the AAP. He says, “The AAP has helped reduce the distance between the public and the ministers. There is now a sense of trust and connection between the two.”

His army background makes voters trust him, he says. “Indian citizens respect the army. They believe that an armyman can bring about efficiency in the governance system,” he says.

During campaigning, he went from door to door in his constituency. “We spoke to them personally, promising to solve all problems once we came to power,” he says.

According to singh, the biggest problem in his area is lease mutation and freehold property. “Due to the actions of corrupt ministers, the houses didn’t belong to residents. In order to renew the lease or even for repairing broken roofs, the officials asked for huge sums of money. We will put a stop to this,” says singh.

He adds, “The other major problems are the poor condition of parks, care- less disposal of garbage, low availability of drinking water and security of res- idents. Wherever I am going, I am talking to the responsible authority there and trying to solve the issue as soon as possible.”

Asked about the road ahead, his response was like a veteran war hero’s. “Once you are in power, it is not hard to accomplish tasks. All you need is willpower.”

Akhilesh Pati Tripathi

Model Town

Akhilesh Pati Tripathi came to Delhi aspiring to be a civil servant. Having cleared the IAs mains twice, he failed to crack the interview. However, unlike other heartbroken students, this simple fellow from UP turned his attention to helping out the residents of the Lalbagh slums.

The soft-spoken Tripathi comes from an entirely non-political family; his father is a retired schoolteacher. With his bearded face and simple clothes, he looks an ordinary citizen.

Tripathi volunteered during the anti-corruption movements led by Anna Hazare. When the AAP was formed, he became a full-time member and was selected as the Model Town candidate for the polls. He went on to defeat BJP stalwart Ashok Goel.

But it wasn’t an easy win. He lived in the Lalbagh slum to be close to peo- ple. “I wanted to have a closer look at the public issues in Lalbagh, Kishorebagh, Kishorenagar, Kamlanagar and Gulabi Bagh areas. so I started living in Lalbagh and centred my protests in those areas,” says Tripathi.

The biggest problem was the non-availability of ration items. “The ration mafia made it difficult for the residents to avail of the ration system. I led a movement against them.” As a consequence, he was beaten up by the mafia and was in hospital for a week. He says, “The mafia attack somehow helped me gain the trust of the slumdwellers. After that, they rallied behind me.”

He launched the Nashamukti Andolan, to get rid of marijuana and alcohol in Lalbagh. “We also went ahead with the ration and oil campaign, along with

a campaign for clean drinking water, which resulted in regular supply of pure water via tankers in the slums,” says Tripathi.

He was jailed several times. “I was imprisoned three times during the anti- corruption movement and once when I raised the issue of the rape and mur- der of a girl in the Rana Pratap Bagh area,” says Tripathi. “Opposition leaders alleged that I was involved in the murder and had me arrested along with 18 colleagues of mine.” Tripathi and the others were released after 12 days, due to relentless rallies and protests staged by the AAP.

He believes that all those hardships have made him a stronger man. He says, “Having seen the reality up close, I will work for the people by being among the people.”

Bandana Kumari

Shalimar Bagh

A few years ago, at a parent-teacher meeting in her son’s school, the principal asked Bandana Kumari, “What do you want your son to be?” she replied, “I want him to be an IAs officer.” Her son retorted, “I don’t want to be an IAs officer, I don’t want to be a minister’s servant.”

Bandana still recalls her son’s response with a shudder. “There is a negative impression regarding politics and politicians among the public. It is necessary to change this perception,” she says.

Winning from shalimar Bagh by a landslide, she aims to change the way politicians are publicly perceived.

Even before joining AAP, she had been fighting for poor women’s rights. “Whenever I saw a situation where a woman was abused or harmed, I rushed to help in whatever way I could,” she says.

Her NGO, Nayi Pehal, works for women’s empowerment and awareness of girl child rights and safety. “When we approached any ministry official to release funds for our work, they asked for hefty commissions. If we didn’t pay, they simply wouldn’t release the funds,” she says. she has worked in the insur- ance sector, in a private lawyer’s office and in a book company, and has found that, in every sector, it’s common for government officials to seek commissions. “The system is not corrupt,” she says, “the people who run it are corrupt.” According to her, the police are not irresponsible by choice. “Even they are under pressure from corrupt politicians,” she points out.?she has been involved with the AAP since the Jan Lokpal protests in 2010.

“I literally lived in the Ramlila grounds during the protests for over 13 days, supporting Anna Hazare’s cause and fasting with him.”

She could relate to Arvind Kejriwal’s saying that the only way to cleanse dirty politics was by getting into the dirt oneself. “I enrolled for candidature from my constituency,” she says, “I was shortlisted with a few other volunteers and was selected after the public voted for me as a candidate.”

During campaigning, she visited most of the houses in her constituency, talking to the voters, listening to their problems and promising a change for the better.

After winning, she has promised to address the issue of rising electricity tar- iff and prices of vegetables, groceries, gas cylinders and other consumer items. she says she will continue working for women’s safety.

Now that she is a people’s representative, has it become hard for her to stand up to expectations? “Not at all. I will continue working hard. There is a slight increase in responsibilities now, but I am ready for it,” she says.

Saurabh Bhardwaj

Greater Kailash

Saurabh Bhardwaj is one of AAP’s young faces. Born and brought up in Chirag village of New Delhi, he won the Greater Kailash seat by a landslide. But back in 2005, he was just another software engineer based in Hyderabad.

One morning, while surfing the news on TV, he came across a poor blind man’s story. His seven-year-old daughter had been molested by her aunt’s brother-in-law in Maharashtra but he couldn’t appeal to the authorities because the hospital never gave him the child’s medical report. Bhardwaj helped him recover the report by filing RTIs and approaching the state Human Rights Commission.

Even then, he couldn’t move the Maharashtra sessions Court as the lawyers made a fuss over translating the case into Marathi. Frustrated by the lawyers’ attitude, Bhardwaj decided to study law. He enrolled in Osmania University, Hyderabad. “My uncle is a lawyer, my grandfather was one too. I always had an interest in the law,” says Bhardwaj. His tireless work on the case led the court to convict the accused for a five-year term.

In 2011, he shifted to Delhi and started working in a Gurgaon-based IT company. “It was then that Anna Hazare’s anti-corruption movement took place. Every day, I would go to the protest site. I could relate to Anna’s stand against corruption.” Bhardwaj became a full-time volunteer for the AAP on its inception in 2012. “I took part in various AAP protests. But I was just a vol- unteer and never a party office-bearer,” he says. When candidates were being enrolled in April 2013, Bhardwaj registered his name. “I got a lot of help from my party colleagues and volunteers during campaigning. I never even thought I would be selected a candidate, let alone win,” he adds.

Now, people are pouring into his house throughout the day. some are con- gratulating him while others are keen to tell him about the problems they face. Asked how it feels to be recognised as a political leader, he says, “It feels strange. When I was making rounds of polling booths on voting day, people who didn’t even know my face would come and say that they voted for me.”

Herein lies the core power of AAP, he feels. “This is not a leader-driven party. This is a party driven by the people.”

He identifies traffic congestion and water availability as the two biggest concerns in his constituency. “We will hold town hall meetings in each area. The MLA fund will be transformed into a Janata Fund for public use only.”n

Reported by Shayak Majumder

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!