Maccoman was a part-Bengali, part-Hindi performance of Macbeth | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Shadipur curates a theatre fest

Sidika Sehgal, New Delhi

Shadipur is an unlikely locality for a theatre festival. A lower middle class colony in West Delhi, it is inhabited by working class people. There are Hindu and Muslim blocks within Shadipur and the neighbouring colony is dominated by Sikhs. Houses are small, tightly packed and criss-crossed by narrow lanes. Nearby Ranjeet Nagar is where many daily wage labourers live.

This isn’t a place that a high-brow theatre-going crowd would visit. But then the Shadipur Natak Utsav was not for them. It was for the locals of Shadipur and the plays were specially handpicked by five residents of Shadipur.

The idea of organising a community-curated theatre festival came from Studio Safdar, an independent space for art and activism. “Some of our inspiration came from knowing the people here. They are interesting in so many ways,” said Sudhanva Deshpande, founder-trustee of Studio Safdar.

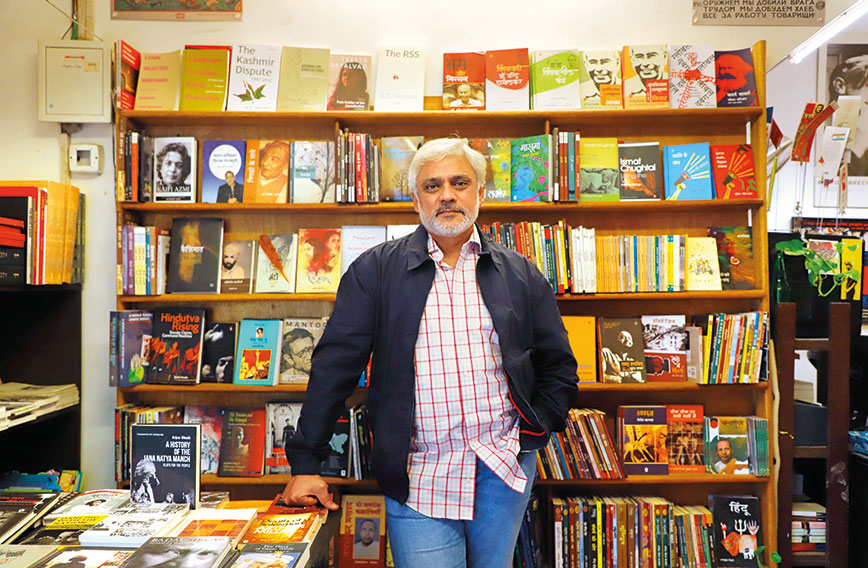

Sudhanva Deshpande, founder-trustee of Studio Safdar Trust | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Sudhanva Deshpande, founder-trustee of Studio Safdar Trust | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

The curators of the festival were Ravi Kumar Otwal, a tea shop owner, Poonam Rajput, a teacher at DAV school in Vikaspuri, Iqbal Hussain, owner of an automobile workshop, Naseem Akhtar, who runs a leather boots business in Sahibabad, and Kamlesh Kumari, who worked for MTNL for 39 years before retiring in 2017.

Over piping hot cups of tea, Otwal recounted his work in a commercial photography studio before he set up his tea stall 25 years ago. He was never much of a theatre-goer till Studio Safdar set up shop in Shadipur in 2012, he admits.

Rajput confessed that the only plays she had seen were the ones held in Studio Safdar. But the influence theatre wields is not lost on her. “What people are unable to communicate through words can reach people very effectively through the medium of theatre,” she says. Otwal echoes her opinion. “You get to learn new things through plays. Something about the country, something about the home," he says. All the curators said they saw theatre as a medium to spread awareness about issues of relevance.

Kumari now grows organic vegetables on the terrace of her Shadipur residence and takes great pride in it. She recalls that when she was working and looking after her children, there was no time to think of much else, least of all theatre. But her daughter is now pursuing a PhD in theatre from Jawaharlal Nehru University. Kumari talks of the excitement of watching a live performance. “It’s not like a film,” she says. “Here you can go and talk to the artistes afterwards.”

Deshpande says that these five people almost self-selected themselves as curators. In June this year, Studio Safdar called a meeting of their 30-odd friends in Shadipur and suggested the idea of a community curated theatre festival. People were taken aback. All this while Studio Safdar would organise the event and the community would support them. But this time the relationship was turned on its head. The brief was that they had to curate the festival and Studio Safdar would provide support.

Deshpande says that these five people almost self-selected themselves as curators. In June this year, Studio Safdar called a meeting of their 30-odd friends in Shadipur and suggested the idea of a community curated theatre festival. People were taken aback. All this while Studio Safdar would organise the event and the community would support them. But this time the relationship was turned on its head. The brief was that they had to curate the festival and Studio Safdar would provide support.

This was unknown territory for most residents and they were initially reluctant to participate. But with a bit of nudging, the five curators emerged. The diversity among curators was a conscious decision — there are two women, two Muslims and one Dalit in this panel of five.

In September, well-known theatre personality Sanjana Kapoor, who is also a trustee of the Studio Safdar Trust, conducted a workshop with the curators. Kapoor’s role was to help them understand who their audience would be and which plays they would want their community to see. There was a play about same sex love which didn’t get selected, but the curators were keen that young people in Shadipur watch the play.

“Do we think about what the play would look like onstage, or do we look at the acting? Is the theme more important? The way she put it, these were points to mull over before taking a decision,” recalled Moloyashree Hashmi, founder-trustee of Studio Safdar. The intent of the workshop was to help the five curators articulate what they liked or disliked about a play. Kapoor was simply moderating their discussions.

Over three days, the curatorial team watched video clips of some 50 entries and selected seven plays. “The curators were aware of the fact that they must bring diversity to what they were curating,” said Deshpande.

Over three days, the curatorial team watched video clips of some 50 entries and selected seven plays. “The curators were aware of the fact that they must bring diversity to what they were curating,” said Deshpande.

The seven plays which they finally chose all had different themes — Kabutar Ja Ja Ja was a solo play about an urban housewife, while Romeo Ravidas & Juliet Devi was about casteism. Shakuntalam – Agar Pura Kar Paye Toh was a comedy in which three clowns tried to perform Shakuntalam. It was the most well-received play.

Each play had its own flavour. Maccoman, The Power Play, was an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth by Madhyamgram Natomon Natya Sanstha, Kolkata. Macbeth became Maccoman in this part-Hindi, part-Bengali performance. The play concluded with the thought that our obsession with stories of kings is actually symptomatic of our desire for power.

Romeo Ravidas & Juliet Devi was an intense play and confronted the audience with uncomfortable contemporary realities. It was loosely based on the murder of Pradip Rathod in Gujarat and the life of Kausalya Shankar, an Indian activist. In March 2018, Rathod, a Dalit, was killed by upper caste men in his village for owning and riding a horse. In March 2016, Shankar’s husband, who was a Dalit, was murdered in an honour killing.

It was a two-actor play in which the duo sang and played instruments. Sharmistha Saha, director and co-writer, said that the play was inspired by the two real-life incidents. A lot of caste and gender issues were brought up during rehearsal. “But it didn’t seem difficult because the discussions were very rich,” she says.

One of the highlights for the performers and for the team at Studio Safdar was that children came in large numbers for the festival. They arrived at the venue before time, bought their tickets and patiently sat through serious plays like Romeo Ravidas & Juliet Devi.

No child was barred from watching a play but they were encouraged to bring some money. “We want children to grow up with the idea that performance is something you should pay for,” says Deshpande. The amount didn’t really matter — some brought a rupee or two, but there were a few who gave 10, even 20 rupees.

Children eagerly wait for a performance to begin | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

Children eagerly wait for a performance to begin | Photograph by Shrey Gupta

A four-level pricing structure was worked out for the festival. For Shadipur residents, the ticket was a mere `20. For people from across Delhi, the cost of the ticket was `200. Children could pay whatever they wished while entry for daily wagers was free. “We just knew that if a rickshawwallah comes, we’re not going to ask him for `20,” said Deshpande.

This differential pricing is a significant indicator of what Studio Safdar stands for. “Just before Safdar (Hashmi) died, he had begun to plan a cultural centre in a working class area,” said Deshpande.

What does it really mean to be a cultural space in a working class area? Studio Safdar and their Mayday Bookstore are designed as spaces where anyone from the local community can walk in and feel at home. Every Sunday, children from Shadipur come to read books and every Wednesday, a film is screened for them.

Deshpande explains that Delhi is culturally skewed in favour of the elite and the rich. All the best restaurants, art galleries, performance spaces, and bookshops are in South Delhi or Central Delhi. In West Delhi, there are a few bookshops and a sparse sprinkling of performance spaces. They wanted Studio Safdar to be in East Delhi or West Delhi. Shadipur is where it all worked out in the end.

The community-curated theatre festival, which was held from November 15 to 22, added a certain effervescence to Shadipur. It was the first iteration of the event and Deshpande doesn’t know what shape it will take, going forward. But it has been a huge success.

Kumari said that many people came up to her to say the selection of plays had been very good. The five curators are happy their choices were appreciated by the community. As Hashmi said, “They realised that they can also curate. It’s not something that can’t be learnt.”

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!