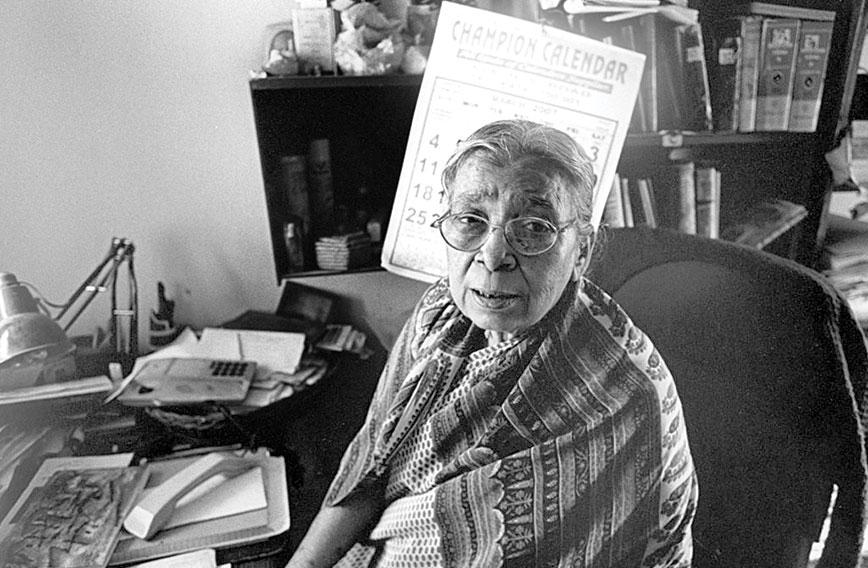

Mahasweta Devi, the compassionate writer

Mrittika Bose, Kolkata

"I have always believed that real history is made by ordinary people.... The reason and inspiration for my writing are those people who are exploited and used and yet do not accept defeat."

This is how Mahasweta Devi, who died at the age of 90 on 28 July in Kolkata, described her work as a writer who dedicated herself to telling those stories that challenged the established order in India.

Her writing stemmed from her political beliefs and activism. She was fiercely committed to fighting oppression in any form and spent a lifetime giving a voice to the unheard. Mahasweta Devi raised her voice several times against the discrimination of tribal people in India. Her activism resulted in the freeing of the statue of noted tribal leader Birsa Munda by the Jharkhand state government in June 2016. The statue showed Birsa in chains as was photographed by the then ruling British government. Her 1977 novel, Aranyer Adhikar, was on the life of Munda.

She spearheaded the movement against the industrial policy of the earlier Left Front government of West Bengal. She stridently criticised confiscation of large tracts of fertile agricultural land from farmers by the government and giving them to industrial houses at throwaway prices.

Old age did not deter her from leading the Nandigram agitation when a number of intellectuals, artists, writers and theatre workers joined together to protest the Left Front's controversial land acquisition policy in Singur and Nandigram. She supported the candidature of Mamata Banerjee in the 2011 West Bengal Legislative Assembly election that resulted in ending the 34-year rule of the Left Front.

Born in 1926 in Dhaka in undivided India to literary parents Manish Ghatak, a well-known poet and novelist of the Kallol movement, and Dharitri Devi, a writer and social worker, Mahasweta Devi's larger family included several culturally distinguished members. Noted filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak was her paternal uncle and noted sculptor Sankha Chaudhury and Sachin Chaudhury, the founder-editor of the Economic and Political Weekly of India, were her maternal uncles. After finishing school in Dhaka, Mahasweta Devi moved to West Bengal after the partition of India. She graduated in English Honours from Rabindranath Tagore’s Vishvabharati University in Santiniketan and completed her Masters in English at the University of Calcutta.

In 1964, she began teaching at Bijoygarh College — then an institution for working-class women students — affiliated to the University of Calcutta. Simultaneously, she also worked as a journalist and a creative writer.

The tribal communities of West Bengal, the Lodhas and Sabars, women and Dalits interested her keenly. She set out to create her own literary identity. One that transcended gender differentiation and all forms of conservatism, totally disregarding the mellow, romantic tradition of Bengali literature. One that was moulded by awareness, experience and sensitivity towards society. The stark reality in her literary pieces was precisely what mainstream readers would rather avoid. Yet these were too strong to ignore.

Mahasweta Devi’s first novel Jhansir Rani, published in 1956, was an indication of the genre of her future literary work. She toured Jhansi extensively, collecting facts and myths, from local people and folk songs, on Laxmibai, the rebel queen. She went on to prove that traditionally recorded history was woefully inadequate as she penned novels like Aranyer Adhikar, Amrita Sanchay, Andhar Manik and numerous short stories often based upon meticulous research, conducted sometimes by unconventional means like oral history and folklore about the people she wrote about.

Bengali readers were jolted out of their comfort zones by Basai Tudu and Hajar Churashir Ma. In many of her novels and stories she brutally laid bare the inadequacies and weaknesses of Indian society. Mahasweta Devi had the sensitivity of a literary writer and the mind of a keen social researcher. The amalgamation gave her writing its uniqueness.

Critics and a section of readers did not spare her for her temerity to rip the sugar coating off the make believe world of Bengali literature. While they tried their best to deride her creations, the revolution in the Bengali literary scene towards realistic writings continued.

She wrote over 100 novels and more than 20 collections of short stories in Bengali, many of which have been translated into other languages.

The quarterly Bortika magazine that Mahasweta Devi edited from 1980 had been a mouthpiece for the most downtrodden in Indian society — the dispossessed tribals and marginalised segments like the landless labourers of eastern India. It was the most natural thing for her to invite a rickshawpuller, Monoranjan Byapari — who asked her the meaning of a difficult Bengali word after ferrying her home in his rickshaw — to write an article about his life in her magazine. He went on to become a prominent writer in the Bengali literary circle.

She was very fond of her sisters, who were all very talented. I remember her looking with immense pride at an impromptu flamenco performance by one of her sisters at a family wedding.

Mahasweta Devi married renowned playwright Bijon Bhattacharya, who was one of the founding fathers of the Indian People’s Theatre Association movement. In 1948, she gave birth to Nabarun Bhattacharya, who became a novelist and political critic. She worked in a post office but was fired from there for her communist leanings. She went on to do various jobs, such as selling soap and writing letters in English for illiterate people. In 1962 she married author Asit Gupta after divorcing Bhattacharya.

I was witness to Mahasweta Devi's softer side twice. The first time she walked across and introduced herself to me. “I have come to make your acquaintance only because of your daughter,” she said, pointing to my toddler daughter whom I had accompanied to her friend’s birthday. Her friend happened to be the author’s grand niece. “She is a lovely child and we have become friends,” she chuckled.

A few years later I went to meet her at her residence to request her to conduct a storytelling session for children at a school fair commemorating Satyajit Ray. I was at first greeted with a curt, “Why have you come?” When I explained that I had grown up enjoying her stories about the super cow 'Nyadosh' published in the children’s magazine Sandesh (co-edited by Satyajit Ray) and had come to request her to regale the schoolchildren with such stories, her face broke into a smile. “You knew I couldn’t refuse such a request, didn’t you?” she said with a twinkle in her eye.

At the fair, the kids sat glued listening to her tales laced with humour, adventure and a unique grandmotherly touch. Surrounded by the wide-eyed eager little bunch, she answered the strangest questions that only children can ask, with perfect ease.

Comments

-

Raynes - March 10, 2017, 6:21 p.m.

It's a pleasure to find such rationality. Welcome to the debate.

-

Kaninika Mitra - Sept. 29, 2016, 8:46 a.m.

Very well written