RAJNI BAKSHI

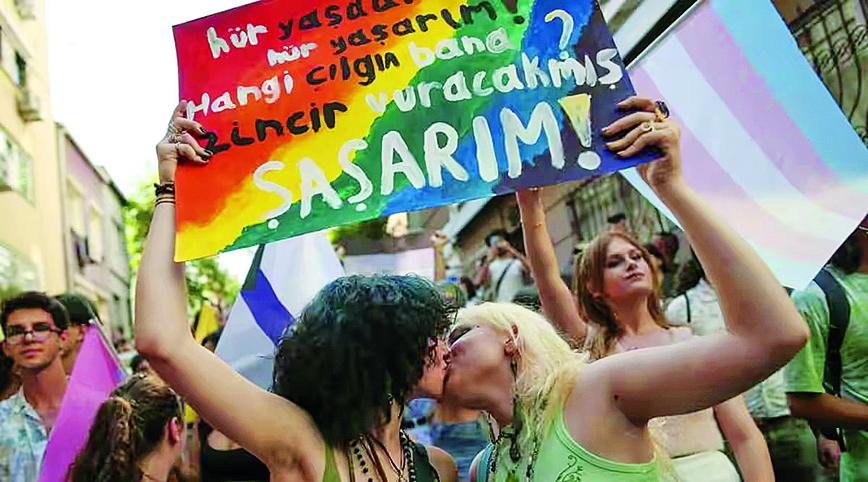

IT is ten years since the annals of nonviolent civil disobedience were enlivened by the ‘kissing protest’ in Turkey. In May 2013, scores of couples locked lips at a subway station in Ankara to protest against the authorities chastizing a couple for kissing in public.

This action quite flummoxed the authorities. What the police are trained to handle is protesters aggressively shouting slogans, waving banners and pushing against police barricades. But what could the police do with hundreds of people just kissing assiduously? Absolutely nothing.

As nonviolence trainer Srdja Popovic wrote about the defiant kissers in Turkey: “It’s not only that the amorous demonstrators aren’t breaking any laws; it’s also that their attitude makes a world of difference. If you’re a cop, you spend a lot of time thinking about how to deal with people who are violent. But nothing in your training prepares you for dealing with people who are funny and peaceful.”

This is an example of what Popovic calls ‘a dilemma action’—that is, an action that forces the authorities into a lose-lose situation. The underlying philosophy is ‘laughtivism’. This term, briefly referred to in the previous column, calls for closer attention.

At first glance ‘laughtivism’ may seem puzzling or even a bit contrived. It is, however, a serious term which refers to strategic use of humour and mocking in order to undermine the authority of those in power. The term has been coined and popularized by the Belgrade-based Center for Applied Nonviolent Actions and Strategies (CANVAS), founded by Popovic.

Much of Popovic’s writing is about the details of laughtivism. For example, an article he co-authored for Foreign Policy magazine in 2013 was titled “Why Dictators Don’t Like Jokes”. It was accompanied by a photo of a Tunisian demonstrator holding his bread stick like a weapon in front of advancing riot police.

The term laughtivism may be newly coined but its practice is well established. In cinema, one of the most iconic examples of this genre is Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator in which Chaplin lampooned Adolf Hitler—conveying powerful insights to his audience even as they laughed.

Popovic’s first step is to challenge the common assumption that laughing as you protest can only be a form of venting frustration but cannot actually make a difference. In his book, Pranksters vs. Autocrats: Why Dilemma Actions Advance Nonviolent Activism, Popovic draws on two decades of experience to demonstrate how an element of play not only melts the protesters’ fear, it can also unmask the weakness of those in authority.

According to Sarah Freeman-Woolpert, a student of Popovic, humour and irony were deployed often during the dark days of the Third Reich in Germany. Writing in the journal, Waging Nonviolence, Freeman-Woolpert says that laughtivism is now being used to counter the revival of Nazism: “Today, the resistance takes the unlikely form of clowns—troupes of brightly dressed activists who show up to neo-Nazi gatherings and make a public mockery of their hateful messages. This puts white supremacists in a dilemma: their own use of violence will seem unwarranted, yet their machismo image is tainted by the comedic performance. Humour de-escalates their rallies, turning what could become a violent confrontation into a big joke. Cases show that anti-Nazi clowning can also turn into a wider community event, bringing local people together in solidarity and fun.”

These experiences show that dilemma actions and laughtivism are potentially as effective against hate-mongers and xenophobic extremists as they are against government authorities. For example, in 2012 local authorities in Russia banned public demonstrations that were bringing thousands out on the streets in protest against the election scandal. Activists in the Siberian city of Barnaul staged a ‘toy protest’.

If people had carried the anti-Putin placards they would have immediately been detained. Instead, protesters propped up the placards on teddy bears and Lego characters. Sure enough, the Siberian authorities removed the placards and banned future toy protests. But, as Popovic writes: “…the government’s clumsy reaction, videos, images, and stories of their decision made national and international headlines.”

Similarly, in 2007, the Panties for Peace campaign highlighted human rights violations in Myanmar. Women across the world sent female underwear to Burmese embassies in various countries. Their purpose was to insult the military junta leaders who apparently believed that any contact with female undergarments — clean or dirty — would sap them of their power.

In two-thirds of the cases of dilemma actions that CANVAS has studied, they found that the actions were replicated by others. You may well ask: What is the good of this ripple effect if authoritarian regimes remain in place? Surely keeping the spirit of defiance alive is an end in itself. And, in the long arc of struggles that challenge brute force with the power of humane values, even momentary achievements command respect and can deepen resolve across generations.

Rajni Bakshi is the founder of YouTube channel Ahimsa Conversations

Comments

-

Chandralekha Anand Sio - Sept. 14, 2023, 12:36 p.m.

Authority should not be confused with complete power. Change should be considered in a positive way when a section of people is unhappy with existing rules or situations.

-

Ravi Duggal - Sept. 13, 2023, 11:15 a.m.

Great piece Rajni. Enjoy reading your column. Nonviolence can indeed be a very powerful tool but the responses of the current regime are increasingly pushing honest and concerned protesters towards the use of violence. And movies like Ungli, Jawan etc promote it to seek justice against failure of governance