ARUN MAIRA

IT takes a child to tell an emperor that he is not wearing any clothes. My seven-year-old grandson made me realize that the Planning Commission and the Government of India were not listening to the people. Driving with me in New Delhi, in my government car with a red light atop, past beggars at traffic crossings, he exclaimed, “What’s the government doing? Counting daisies?” The Planning Commission, of which I was a new Member, was trying hard in those days to prove, with statistics, that poverty had greatly reduced in the country since the liberalization of the economy.

I explained to Viren that evening what the purpose of the Planning Commission was, and I brought him the next day to the Planning Commission to show him my big office and to introduce him to the many personal staff attending to me, who spoiled him with biscuits and sodas. When Viren returned to his school in the US, he had to write an essay, like other students, on what he had done during his summer holidays. Viren wrote a 14-page book on the Planning Commission of India, with sketches he had drawn too.

At the end of his book, he referred to the Planning Commission as the “Planning Community of India”. There was a picture of a man in a big office behind a big table, across which sat a skinny man with folded hands. Viren wrote below it, “The Planning Community is a place where all the poor people of India can come, and there will be someone there to listen to them, and then they will not be poor anymore.” That’s how the Planning Commission should function, he implied. But it wasn’t. We were analyzing statistics and arriving at conclusions about the economy the ‘scientific’ way. We were not listening to real people to understand their real problems.

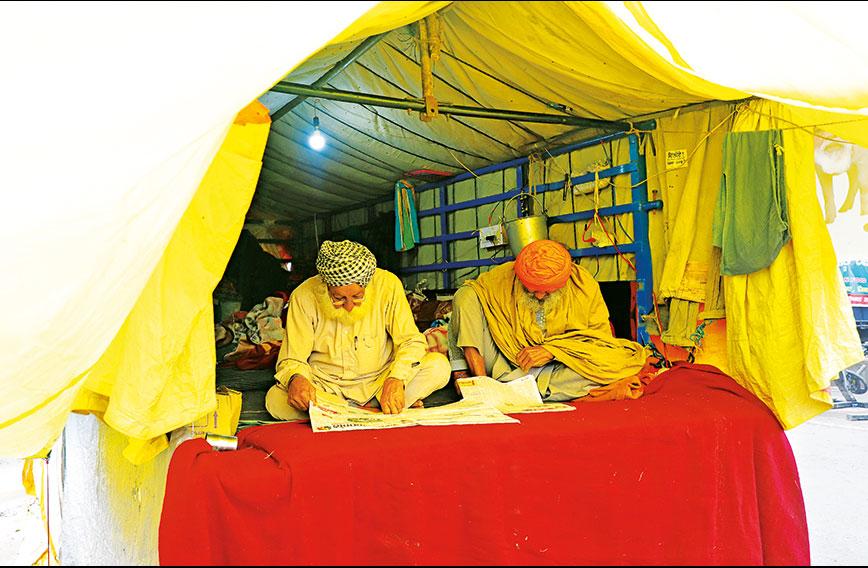

Thousands of farmers, many with their wives and old parents, camped around India’s capital for a year during the COVID-19 pandemic, demanding that the central government hear their views about the new farm laws the government had rammed through Parliament without even a discussion there. The government refused them permission to come into the city to make their views heard outside Parliament. The government claimed that the views of stakeholders had been considered already and these farmers were obstructing reforms that would increase their incomes. Experts had examined the data, it claimed, and the best scientific minds had opined. The farmers said the experts were misguided in their solutions.

The Supreme Court had to intervene to break the impasse. It appointed a committee to hear all sides. The committee submitted its report but the Hon’ble Court did not take further action. Meanwhile, the government conceded the farmers’ demand to withdraw the controversial laws. It is obliged to go back to the drawing board. But will it listen to the farmers this time, whose incomes the government had promised to double and has failed to, and who are the real experts about the conditions in which they work and live?

The committee which was set up to listen to farmers, who are the principal stakeholders in the reforms, seems not to have heard them much, as records of its consultations reveal. Perhaps that is why the Court chose to set apart its report. The committee had interacted directly, either through video conferencing or physically, with only 73 of the 306 farmer bodies it had invited for consultation. The committee also claimed that of the 19,207 representations it received as online feedback on its portal, two-thirds supported the farm laws. But the report also shows that out of the 19,207 responses, only 5,451 came from farmers. Similarly, of the 142 representatives who participated in the meetings of the committee, only 78 were from farmer organizations while 64 belonged to industry bodies and other organizations. It is also very likely that the industry bodies made their case in more modern scientific terms than earthier, less “educated”, tillers of the soil could.

I made it my business in the Planning Commission to observe how the government listens to citizens. The Maharashtra government mandated that city improvement plans be posted for feedback from citizens before implementation. Pune’s plans were posted on the municipal website and citizens were invited to comment within 30 days. Slum dwellers could not download the large files. Even if they could, they could not understand the experts’ language. When they could give any suggestions in time, the experts dismissed most as not making sense.

The Planning Commission used less high-tech, traditional methods. Selected representatives of citizens were invited, TA/DA paid, to meetings in the Planning Commission. They sat around U-shaped tables, a senior official of the Commission at the head. The official would make some opening remarks; then each person around the U would be allowed to speak briefly. They would be assured their views were noted; meeting ended. The overall numbers so cursorily consulted would be totalled. Reading the final plans full of numbers, the people knew they were not heard. The Commission was “counting daisies”, as Viren said, not listening to the people.

The greatest indignity for a human being is to be considered merely a number, like prisoners in concentration camps. When a human being is looked in the eye and listened to with respect, she is acknowledged as an equal human and becomes richer in dignity. Moreover, poor people in slums, those working in informal enterprises, and those toiling on farms and construction sites, who constitute the majority of Indians, have practical knowledge of their problems, and the possibilities in their circumstances. Tracking GDP and stock market indices cannot reveal the realities of the lives of 97 percent of India’s citizens who have no investments in markets, and for whom GDP is pie in the sky. If the government really listened to them, its urban renewal, agricultural, and employment policies would have greater effect in improving their lives.

So, let’s talk about how we can listen better to people not like ourselves, and also listen to the biases within our minds that are dividing us.

Arun Maira is the author of Listening for Well-Being: Conversations with People Not Like Us.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!