Chandra Bhushan

The District Mineral Foundation (DMF) was conceived as a transformative institution to ensure that those who bear the brunt of mining activities also share in its benefits. Established in March 2015 under the Mines and Minerals (Development & Regulation) Act, the DMF is designed to channel a part of its mining royalty into improving the lives and livelihoods of affected communities. However, a decade later, DMFs are struggling to fulfil their mandate. A detailed assessment of 23 states and key DMF districts by us paints a concerning picture.

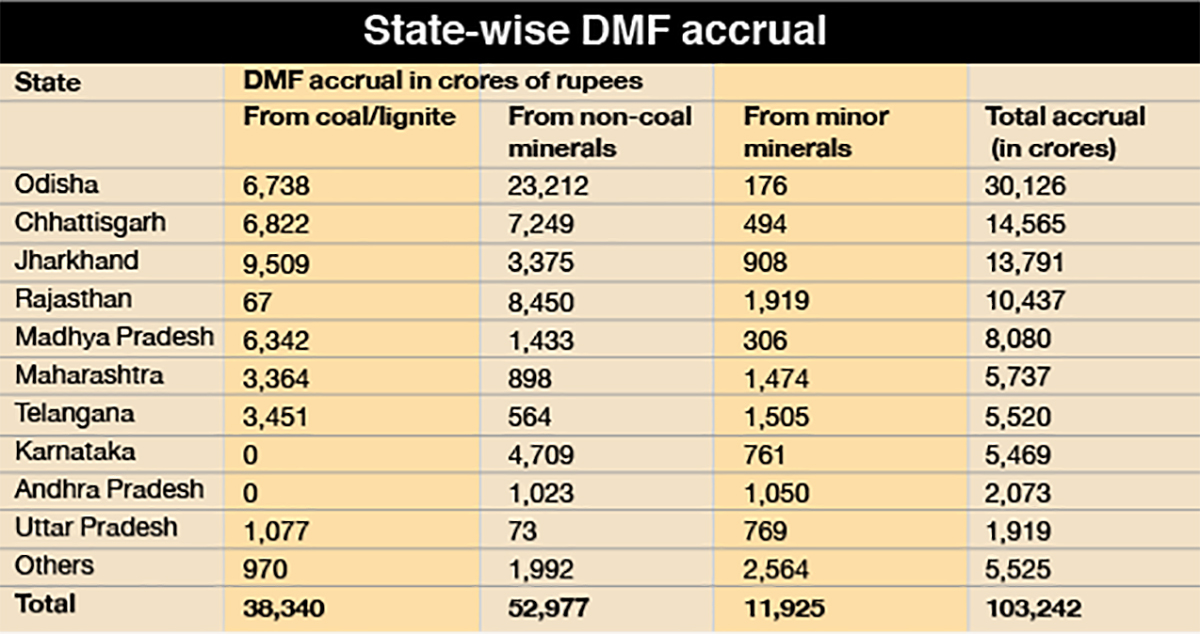

While DMFs across the country have collected over `103,000 crore, only about 40 percent of the funds have been utilized. Worse, much of this spending has been directed towards capital-intensive projects — roads, bridges, buildings, parking lots, and water pipelines — projects that should ideally be funded by state and Central government budgets. The projects that matter most to mining-affected communities — livelihoods, skills, education, health, support for small businesses and freedom from destitution and hunger — have received minimal support.

With India’s continued economic growth and increasing mineral demand for energy transition and net-zero goals, this fund will continue to expand. Our projections indicate that over the next 10 years, `250,000 crore to `300,000 crore could be collected. If this money is utilized prudently, it can transform the lives of millions of the country’s poorest people. We must therefore ask: Will DMF be yet another noble initiative that failed to deliver, or will it evolve into a truly participatory and people-centric institution working for the benefit of mining-affected communities?

Intent vs reality DMF came into being after a decade-long discussion in the country on the issue of the ‘resource curse’. The fact that India’s richest mining districts are inhabited by some of its poorest people prompted the government to set up DMF as a non-profit trust. Mining companies are required to contribute an amount equal to 10 to 30 percent of royalty to DMFs for investments to improve the lives of mining-affected people. In September 2015, the Government of India launched the Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana (PMKKKY) to guide the DMFs on the planning, prioritization, and utilization of these funds.

At present, DMFs exist in 645 districts but the funds are largely concentrated in 50 districts. In fact, the top 21 districts, which have each collected at least `1,000 crore in the past 10 years, account for nearly two-thirds of the total DMF accruals. These districts are also largely tribal-dominated with high multi-dimensional poverty.

Our assessment shows that the biggest challenge with DMF implementation is governance. DMFs in all districts essentially function as extensions of the District Collectorate, with district collectors/magistrates chairing both the Governing Council (GC) and Managing Committee (MC), undermining the accountability of the institution. Additionally, the GC and MC are dominated by officials, MPs, and MLAs/MLCs, with minimal representation of mining-affected communities, despite legal provisions for their participation. Worse still, none of the districts has identified mining-affected people, making it easier for DMF projects to be dictated by district administrations rather than community needs.

Planning for investments is also unstructured in most districts. While annual and perspective planning is mandated under the PMKKKY, no DMF has developed a structured annual plan or published a five-year perspective plan. Most projects are approved in an ad hoc manner without comprehensive needs assessments involving the gram sabhas, which is another legal infringement.

The failure of the institution has translated into misallocation of funds. Consider the case of Jharkhand, where over 40 percent of DMF funds have been allocated to large piped drinking water projects, which are delayed. Decentralized projects would be better. Similarly, in Chhattisgarh, education funds have been spent building schools and hostels instead of on teachers and learning materials.

The lack of investment in human capital is particularly concerning. Our analysis shows that across the country, less than 5 percent of DMF funds have been spent on employment generation initiatives. In mining districts like Dhanbad and Kendujhar, where thousands of workers have lost livelihoods due to mechanization and mine closures, DMF has failed to provide meaningful alternatives. To make DMFs an effective instrument for social justice, the following reforms are critical:

Reform governance: DMFs should be independent and community-led. Mining-affected communities should have one-third representation in the GC and MC.

Participatory planning: All DMFs should be required to develop five-year perspective plans based on comprehensive community consultations.

High-priority sectors: The revised PMKKKY guidelines should be strictly enforced to ensure that at least 70 percent of DMF funds are spent on critical needs like healthcare, education, livelihoods, and skill development.

Oversight: DMFs should be subject to mandatory social audits and financial reviews by independent agencies and the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG).

Endowment fund: DMFs should create endowment funds to support economic diversification and just transition strategies for workers and communities affected by mine closures.

A decade after its creation, the DMF remains a work in progress. The problem is not a lack of funds but rather a lack of vision and political will to ensure that the DMF serves its intended purpose of improving the lives of people impacted by mining.

Chandra Bhushan is one of India’s foremost public policy experts and the Founder-CEO of International Forum for Environment, Sustainability & Technology (iFOREST)

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!