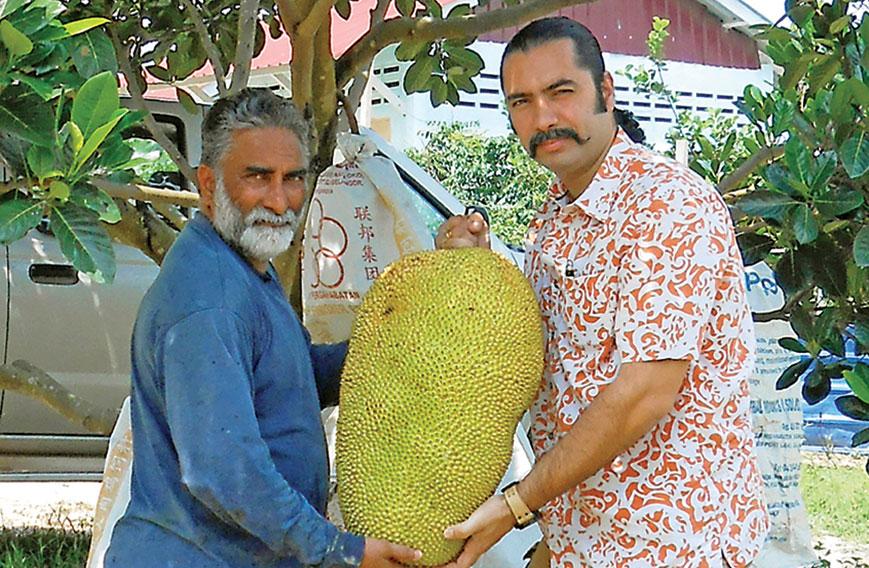

Manmohan Singh and Harvinder Singh with a prized jackfruit from their farm

Punjabi jackfruit quest succeeds in Malaysia

Shree Padre, Kasaragod

Jackfruit isn’t prized in Punjab. It doesn’t have the status of the aromatic basmati rice or the tongue tickling sarson ka saag. Yet two Punjabis, Manmohan Singh and Harvinder Singh, whose families migrated to Malaysia decades ago, are running a successful 30-acre jackfruit farm in Pahang district of Malaysia.

They started their farm in 2012 and named it Barqat, which means ‘blessed’ in Punjabi. In just four years they have become seasoned jackfruit farmers.

When Malaysia’s agriculture department recently held a jackfruit competition in Sarawak, many senior farmers sent their jackfruits to compete. Barqat Farms’ jackfruits walked away with the second prize.

“We started jackfruit farming accidentally,” say Manmohan and Harvinder. “We began with ‘zero’ knowledge, but now, after five years, we are happy to say we have learnt and we feel very content.”

While 38-year-old Harvinder Singh belongs to the third generation of Indians who settled in Malaysia, 55-year-old Manmohan Singh represents the second generation.

Harvinder’s grandfather, Gajjan Singh, came to Malaysia in the early 1900s and joined the police force. Harvinder works in a financial investment company. Manmohan’s father, Saun Singh, left India in the early 1950s. He too joined the police initially and then went on to join the IT sector before becoming a jackfruit farmer.

Both of them have reason to be proud. India doesn’t have a single state-of-the-art jackfruit orchard like the one they have in Malaysia.

HOW IT BEGAN

Five years ago Manmohan, while attending a meeting with his boss, came to know that the Malaysian government was giving land on lease for agriculture. The idea of farming appealed to him. His close friend, Harvinder, also showed interest.

Decades ago, Harvinder’s grandfather had started rubber farming in Malaysia. “I recalled accompanying my grandfather on his rounds of the farm with some nostalgia,” he says.

In 2002 the Malaysian government started a Permanent Food Park project named Taman Kekal Pengeluaran Makanan. Areas were identified that would grow only fruits and vegetables consistently. Planting rubber or palm oil was not allowed. Till date the Malaysian government has developed 54 such Permanent Food Parks. A new one started recently has set aside 3,600 hectares for food crops.

The land is given on lease to people keen to farm at 100 ringgits per acre per annum. Permission has to be renewed every year. The government has the right to take back the land if any terms of the agreement are violated.

The main crop most farmers have selected is jackfruit. Orchards of jackfruit cover roughly 52 percent of the area. The most popular jackfruit variety is J-33. Some farmers have planted J-37 (Mastura) and J-35 varieties.

Manmohan and Harvinder got down to work as soon as land was allotted to them. All wild growth was swiftly cleared and a fence was built. Barely two months after getting possession, they completed planting.

How did two greenhorn farmers know what to plant and how? “The agriculture officers in Malaysia are quite knowledgeable and very cooperative. Whenever you approach them for guidance, they help you,” says Manmohan.

They also approached experienced farmers for advice, whenever required. One farmer, for instance, advised them on bud grafting or patch budding, a system that helps a sapling yield jackfruit in just two years.

“In addition to these two resources, you have another friend too — the internet,” quips Manmohan.

SEASONED MARKETS

Manmohan and Harvinder planted 1,300 trees on their 30 acres. While Manmohan looks after production and management of the farm, marketing is Harvinder’s responsibility.

They opted to plant the J-33 variety, popular in Malaysia. It is also called Tekam Yellow. J-33 sells for the highest price. Unlike India, Malaysia is very quality conscious about jackfruit.

Some Malaysian farmers grow varieties like Mastura and Subana too. “Our country has the saffron fleshed variety as well,” says Manmohan. “But customers don’t like it because it is not very crispy and tastes slightly sour. This variety sells for about 80 cents per kg, whereas the best quality fruits fetch thrice this price. Farmers who have planted the saffron variety are quite disappointed.”

Manmohan and Harvinder have invested equally. Each has spent 57,000 ringgits or about Rs 919,720. One great advantage Malaysia has is that jackfruit grows throughout the year though production declines in March and April.

Generally, trees start yielding jackfruit in three years. Barqat Farms got its first harvest in August 2015. Till last December, they were collecting 80 to 100 fruits per month. In the third year their trees yielded 330 fruits and they earned 6971.30 ringgits or Rs 112,485. Yields usually increase from the fifth year onwards. Manmohan and Harvinder are hoping to break even by then.

At present only one-fourth of the trees have started fruiting. Some trees grow fast and others slowly in the initial years. The two farmers are trying to boost the growth of slow-growing trees by giving them an additional quota of fertilizer. “Next year, almost all our trees will bear fruit,” they hope.

Jackfruit that weighs more than 10 kg is categorised as an ‘A grade’ fruit in the market and sold for about 2 to 2.60 ringgits per kg. Jackfruit below 10 kg is listed under ‘B grade’ and fetches around 1.50 ringgits per kg. If the fruit weighs 9.5 kg, it is still categorised as B grade.

Wholesale jackfruit traders in Malaysia are of two kinds — those who buy fruits for making vacuum dried chips and those who buy fresh fruit for consumption. The first category isn’t finicky about variety. The second buys only A grade fruit.

The carpels of B grade fruit aren’t big and thick enough. But weight doesn’t necessarily mean quality. “Jackfruit between 15-22 kg are considered the best,” says Harvinder.

For an orchard of jackfruit, Malaysia’s department of human resources has fixed a norm of two farmhands for 20 acres.

Manmohan and Harvinder have employed two permanent farmhands. Apart from monthly salary, they are provided accommodation, water, gas, electricity and an insurance coverage of 25,000 ringgits. Once production improves, more labour will be required.

Jackfruit trees provide good commercial yield for about 25 years, beginning from the fifth year. After that, yield starts declining.

Farmers then identify the old trees for replacement. The entire orchard is not replanted but replaced in a staggered way so that the farmers’ income doesn’t decline drastically.

Most Malaysian jackfruit plantations are irrigated, enabling fruit size and productivity to increase by about 20 to 30 percent. The Singhs haven’t started irrigating their farm though water is available. Irrigation infrastructure including pipelines requires considerable capital investment.

Manmohan visits the farm at least five times a week and spends a minimum of three hours. If required, he joins his workers in spraying, harvesting and other operations. During the weekend, he spends 8 to 10 hours working on the farm. Every week, the farm requires 40-50 hours of his time.

RAISING JACKFRUIT

Jackfruit farming is very advanced in Malaysia. Farmers decide not only the height of their trees but also the number of fruits the trees will yield and what their weight will be.

Six to 18 months after planting the grafts, farmers begin canopy management of the young trees. If two branches are growing too close together, they pull them apart and tie them. Or they tie a stone or any weight to one branch to keep it away from the other. A wider gap makes it easier to carry out agricultural operations once the fruit is ready for harvesting.

When the plant grows to a height of four to five feet, farmers cut branches at the lower level to increase ground clearance. A gap of two feet is created between the branches at the lowest level and the land.

The tree is pruned when it reaches a height of 12-15 feet. This technique prevents the tree from growing vertically and induces it to grow laterally. The tree is generally permitted to grow up to 12-15 feet. This restriction helps to harvest the fruit by standing on the ground. You don’t have to climb the tree.

“Since we have limited labour, we harvest fruit twice a year,” explains Manmohan. “The height of an average man is between five to six feet. His hands can reach another two to three feet. We create a situation whereby our staff doesn’t have to climb the tree at all. So tragic incidents of people falling from jackfruit trees don’t happen here.”

Pruning serves many purposes. It contains the height of the tree and ensures branches spread out in different directions so that the entire tree gets air and sunlight. Productivity increases and so does the quality of fruit.

Thinning is another important agronomic practice. That means removing excessive fruit. Every month farmers here cut off young fruits that sprout at the top of the tree so that they don’t need to harvest fruits from that height.

Also fruits growing at the top can break branches. Sometimes if branches are weak, farmers use props to hold them up.

Thinning has many advantages. The fruit grows bigger and carpels too turn thicker, bigger and tastier. Since thinning prevents fruits from overlapping, the likelihood of an insect attack is lowered.

Certain norms are followed. Only two fruits per month are harvested from a tree. Not more than two fruits per branch are grown to ensure quality and prevent the branch from breaking. Keeping tree health in mind, farmers prefer to grow fruits in a layered way on different branches. This management practice ensures fruits of uniform size too.

To control fruit fly menace, the fruit is bagged when it is tender. The date of bagging is painted on it so that the farmer knows when the fruit should be harvested. In areas where there is theft, instead of writing the date, a code is used to confuse the thieves.

Generally, jackfruit takes 120 days to ripen. The bags are opened exactly 110 days after bagging. To check if the fruit has ripened, the fruit is tapped with fingers. A hollow sound means the fruit is ready for harvesting.

“Jackfruit can be harvested within 100 days,” explains Manmohan. “But it’s better to wait for 115 days. Transport and reaching the end consumer takes another four to seven days. So when the fruit reaches the final buyer, it is just ready for eating.”

DEMAND AND SUPPLY

In the Pahang Food Park, five people with roots in India are cultivating jackfruit. In Malaysia, jackfruit plantations are extending in a big way. Currently it is a very popular and remunerative crop. But is the proliferation of jackfruit orchards a matter of anxiety for these partners?

“Right now, demand is exceeding supply. We don’t need to worry for a decade. What will happen after that, we don’t know,” says Manmohan.

Since there is good demand for fresh jackfruit, Malaysia hasn’t tried value addition apart from making chips. Reassuringly for farmers, jackfruit hasn’t witnessed a market crisis or production failure so far. Systematic thinning and permitting only a limited number of fruits to grow have ensured that the market is not flooded with fruits.

Some Malaysians use tender and raw jackfruit as a vegetable. Harvinder says you need a 20-acre plantation to make jackfruit cultivation a viable financial proposition.

But, for the two Punjabi families, jackfruit still isn’t a fruit they feast on.

Although they grow tonnes of jackfruit they don’t consume even one full jackfruit a month. “Jackfruit isn’t a popular fruit in both our families. Maybe because it grows bountifully on our own farm, even our children don’t eat it with interest,” says Harvinder. “They do eat jackfruit chips, though, and they love farming.”

Contact: barqatplantations@gmail.com

Comments

-

ranadeer - June 4, 2018, 4:42 p.m.

Best

-

Gurmel Mouji 2 - Feb. 1, 2018, 5:51 p.m.

Very nice and valuable article for the Punjab farmer in dire need of viable diversification in cropping patterns and currently trapped into growing water-guzzling rice and wheat.

-

Ang GH - Oct. 24, 2017, 6 p.m.

Interesting to know your comment about the demand and supply of jack fruit in Malaysia. I just wonder if you can make jack fruit chips from your farm there will be good market. I am looking for dried jack fruit. Thanks.

-

Basavaraj - Sept. 3, 2017, 12:05 p.m.

Dear sir, I would like to cultivate jackfruit plantation ie J 33.So please let me know the marketing aspects and details for cultivation. With regards Basavaraj. Shivamogga, Karnataka,India.

-

musoke Deo - Feb. 5, 2017, 9:50 p.m.

I need to know the various processed products that can be obtained from jackfruit.

-

Mneme George - Dec. 6, 2016, 1:18 p.m.

Good article by Shree Padre. Makes and interesting reading and informative throughout.