Ng Teng Fong General Hospital in Singapore

Redesigning the hospital for more air, natural light

By Sanjay Prakash

If hospitals today seem to be built like boxes which hundreds of people enter with different diseases, it was not always so. Until the early 20th century, natural ventilation and daylight were considered primary architectural provisions for a hospital building, initially provided by Italian Renaissance architects.

By the 1950s, with the advent of antibiotics and improved aseptic practices, the medical establishment started believing that patient health could be maintained regardless of room design. (Some doctors even preferred the total environmental control offered by air-conditioning, central heating, and electric lighting.) Windows were no longer necessary for healthy hospitals, and by the 1960s and 1970s even window-less patient rooms appeared. Efficiency trumped health.

The pandemic has shown us that we should perhaps opt for less congested design. The pendulum is swinging. In 1984, hospital architect Roger Ulrich published an article that had one clear and influential finding: Patients in hospital rooms with windows improved at a faster rate and in greater percentage than those in window-less rooms.

The belief that the physical environment of a hospital could affect the recovery of patients has existed since ancient times. However, it is difficult to support this assumption because randomized controlled trials — although often conducted in medicine — are rarely adopted in architecture. However, this significant improvement in recovery time has lately been established beyond doubt.

Full-spectrum light prophylactically controls viral and bacterial infections and also significantly improves physical working capacity by decreasing heart and pulse rates, lowering systolic blood pressure and increasing oxygen uptake.

Inadequate light has a direct effect on fatigue, disease, insomnia, alcohol addiction, suicide and other psychiatric diseases. Through analyses of a large medical database, it has been demonstrated that patients with beds next to the window had a shorter length of stay than those next to the door.

Spanish philosopher Ivan Illich argued that a major threat to health in the world was modern medicine and that hospitals, in particular, caused more sickness than health. He popularized the word iatrogenesis to describe what he saw as a relentless increase in disease induced by doctors.

Can large hospitals also be naturally ventilated? Well, Singapore has demonstrated a modern example by doing exactly that! Despite its warm and humid climate, the Ng Teng Fong General Hospital has taken advantage of plant scaping and water bodies to produce a cool environment and naturally ventilated wards (see picture on next page). For those of us who tout Singapore as an example of a hyper-modern society that we would like to emulate, this is something to ponder.

Public health system design, however, is not the same as hospital design. Public health consists of a whole network of primary and community health centres that mesh with small and large clinics and hospitals. Good hospitals do not necessarily contribute to good health outcomes: it is the network of centres that creates good health outcomes.

The Indian network of healthcare systems is designed to be organized into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. The primary level centres are called sub-centres and Primary Health Centres (PHCs). At the secondary level there are Community Health Centres (CHCs) and smaller sub-district hospitals. Finally, the top level of public care provided by the government is the tertiary level, which consists of medical colleges and district/general hospitals. The number of PHCs, CHCs, sub-centres and district hospitals has increased in the past six years. The specifications are mandated by the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS), which operates under the National Health Mission. Since not all facilities are up to the standards set by IPHS, this system tends to be only a wishlist rather than a specification. It is still very far from reality.

Assuming that we can deploy the resources to fulfil the shortfall, both in terms of numbers as well as the quality of each such centre, we would need 40,000 PHCs (for rural areas alone) but we have (in rural areas) under 25,000 currently, many of dubious quality. There is a strong case for having smaller and locally accessible hospitals and health facilities — where undoubtedly the patient load would also be less. Given the backlog in hospital facilities, more hospitals/PHCs need to be built quickly.

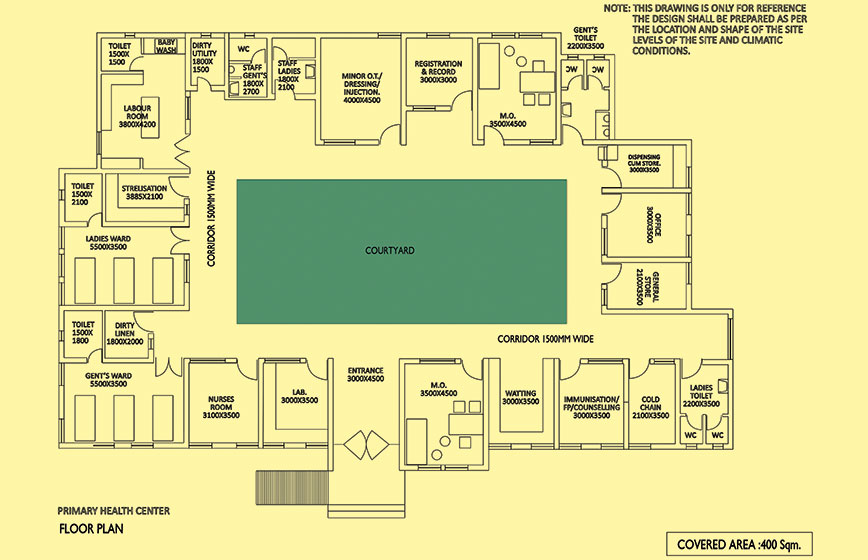

Plan of a redesigned hospital with a courtyard

Plan of a redesigned hospital with a courtyard

Also, unfortunately, while this network is designed to be a network of referral centres, there is a tendency to shortcut the process and treat referral institutions as primary centres. Due to our tendency to self-medicate, patients flock to referral facilities directly. In any case the network is conspicuous by its absence and we treat each centre as an independent entity.

At the CHC or PHC, as well as at sub-centres and sub-district hospitals, the IPHS does not specify air-conditioning (except for specific spaces within the facilities such as blood banks, operation theatres, ICUs, NICUs, post-mortem and heat stroke rooms). IPHS does say that the spaces should be well-lit and ventilated with as much use of natural light and ventilation as possible. It also allows that the layout may vary according to the location and shape of the site, levels of the site and climatic conditions.

Unfortunately, these documents provide sample layouts for various levels of facility, and these tend to become the standardized design used by government agencies and replicated all over the country.

Can these same designs be naturally lit and cross-ventilated? The answer is a simple yes. SHiFt, an architects’ office, has worked out how, for a single-storeycentre, cross-ventilation can be achieved either with a depression of the corridor ceiling and providing ventilators, or, for a four percent extra area, reworking the layout so as to become singly loaded around a courtyard, thereby making it much better for patients (see drawing on previous page).

Though the IPHS specifications seem to emphasize infrastructure, the government is not in the way of providing small and well-lit naturally ventilated facilities.

The IPHS asks for the location of a health centre to be central and accessible with an all-weather road, water supply and a proper boundary, but there is no mention of central air-conditioning. It is only sought for larger facilities such as a sub-district/sub-divisional hospital.

Even here it says that good natural light and a pleasant environment would also be of great help to both patients and staff. Of special interest is the stipulation on ventilation, which states that this may be achieved by either naturally or by mechanical exhaust of air.

Unfortunately, due to the difficulty of designing well-lit and ventilated spaces, most architects design spaces to be centrally air-conditioned (a lazy way to design), especially in the private sector (where air-conditioning is associated with being able to charge a higher fee).

This malaise has grown so bad that we have come to associate all hospitals and clinics with black boxes with central air-conditioning and artificial light. This expectation is disastrous for the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19, of course.

There is also a need to look at supplying oxygen which will be easier to provide in ventilated spaces — in fact, such spaces will tend to require less provision of oxygen.

Now let us look at the temperature setting. The IPHS specifies that the temperature for neonatal care should be maintained at 28 degrees C plus or minus 2 degrees C round the clock, preferably by thermostatic control.

The temperature inside special newborn care units (SNCU) should be set at the level of comfort (22 degrees to 25 degrees C) for the staff so that they can work for long hours, by air-conditioning provided the neonates are kept warm by warming devices. Unfortunately, once provided, air-conditioning systems are set to deliver temperatures of 22 degrees to 25 degrees C, not 28 degrees C plus or minus 2 degrees C, thereby making it impossible to achieve that lower temperature by natural ventilation and light alone.

As acclimatized Indians, we do not complain of the heat as long as temperatures remain under 30 degrees C, so it is possible (but requires research) that all air-conditioning should aim to deliver only 30 degrees C, not (much) lower temperatures. Not only will this save energy use, it will also be much healthier for not causing hospital-induced infections, which is a common occurrence.

Sanjay Prakash is principal consultant at SHiFt - Studio for Habitat Futures

Comments

-

Amit Kumar Bose - Aug. 2, 2021, 8:21 p.m.

Very interesting point of view! Stands to reason.