KIRAN KARNIK

NEVER before has science touched the lives of more people than it has in the last few months. “Touched,” literally: thanks to the Covid vaccine, now already administered to about three billion people around the world, including over 400 million in India. The near-ubiquitous mobile phone has, after more than two decades of widespread availability in India, reached about a billion people; a figure that may be overtaken within a year by the number of those vaccinated.

The successful development of multiple vaccines in under a year is one of the greatest triumphs of science. Scientists from academia and research laboratories in various countries worked with business organizations and hospitals to first develop and then test the vaccines, before rolling them out for general use. In an increasingly protectionist world, science has demonstrated the power and necessity of global cooperation and collaboration. It has also highlighted the importance of science, of creating and nurturing scientific talent, and of investment in R&D. A key element in this, one that underlies the success of science, is scientific temper.

Yet, in a negation of scientific temper, even as the country seeks to ramp up the vaccination rate from five million jabs a day to 10 million, there are signs of “vaccine hesitancy”. Based partly on a few cases of severe after-effects, this hesitancy is largely driven by vague fears, rumours and stories. Such reluctance and refusal to be vaccinated is limited but world-wide, including amongst the educated in “developed” countries. Despite the extensive use of the products of science in our daily life, a fair number of people lack a scientific temper.

In recognition of the importance of scientific temper, our Constitution says: “It shall be the duty of every citizen of India to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry.” But what exactly is scientific temper? The concept was popularized in India by Jawaharlal Nehru, who defined it (in The Discovery of India) as: “The scientific approach, the adventurous and yet critical temper of science, the search for truth and new knowledge, the refusal to accept anything without testing and trial, the capacity to change previous conclusions in the face of new evidence, the reliance on observed fact and not on pre-conceived theory, the hard discipline of the mind. All this is necessary, not merely for the application of science but for life itself and the solution of its many problems.”

Clearly, scientific temper — especially to question, search, and to be guided by fact rather than preconceived theories — is essential for the progress of science. However, it is the last part of Nehru’s elucidation that is particularly important, with scientific temper serving as a guide to our daily lives. In a recent paper, eminent scientist and thinker Dr Raghunath Mashelkar, former Director General of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), puts it well: “Scientific temper is a way of life, in terms of both thinking and acting. It consistently uses the principles embodied in scientific method. It involves the application of logic. Discussion, argument and analysis are vital parts of scientific temper. Elements of fairness, equality and democracy are integrally built into it.”

Dogma and theology are the very antithesis of scientific temper. They abandon logic, thinking and questioning, depending instead on given and eternal truths. If science followed this path, we would yet believe that Earth is flat, it is at the centre of the universe and the sun revolves around it. If dogma ruled, science would be dead, as would the agency and freedom of individuals.

Yet, even when we decry superstition, it is necessary to apply the scientific method. Thus, to those who believe that walking under a ladder is inauspicious, it is better to understand and explain that this must have originated from a few actual experiences of ladders falling on people. It is, therefore, scientifically wiser to go around — rather than under — the ladder. So also with much of superstition: given limited knowledge and data, certain behaviours or practices may have been appropriate. Now, with new findings and information, they must change.

In some areas there are “holy groves” or particular trees considered sacred. This must have originated from the need to protect trees, and in days gone by this was most easily achieved by either religious sanction or a feudal firman. This short-cut method may have saved many trees, but at the cost of obstructing thinking, understanding and science. It is, therefore, not a sustainable approach, nor one that can lead to a broader appreciation of ecological imperatives. Little wonder that we see massive cutting of trees and the denudation of forests with increasingly disastrous consequences.

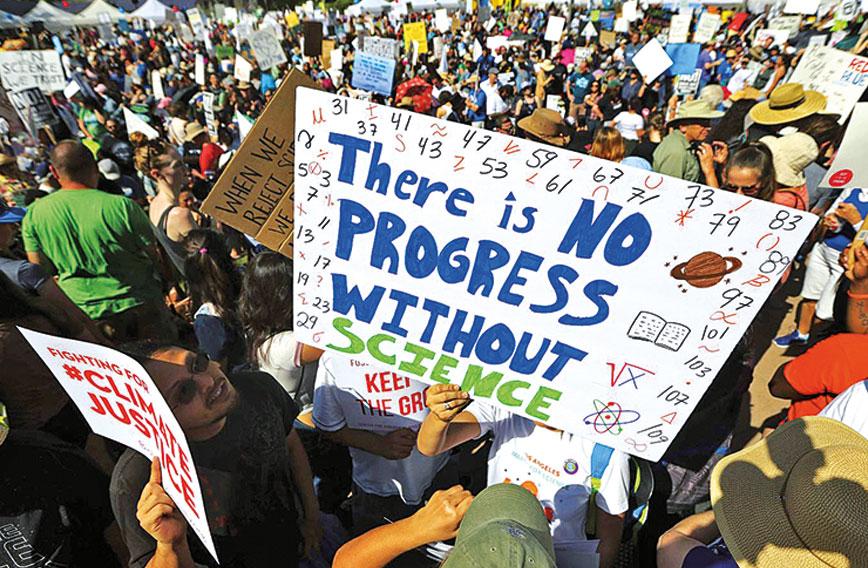

New ideas and theories, experiments and validation, new technologies and products — all are the result of the method of science, or scientific temper. Its emphasis on questioning, debate and dissent, with a constant search for verifiable truth, is of essence to the progress of science. It is also key to the progress of society, and a country without a widespread scientific temper is unlikely to lead in science or in societal innovation and well-being.

Despite many official pronouncements and much lip service, we are yet a society imprisoned by dogma and blind superstition. In recent years, with increasing emphasis on religion across communities, scientific temper has taken a big hit. Humility, openness and doubt, which stimulate questioning and dissent, have all been smothered and replaced by the smug and arrogant certitude of theology and dogma. This hardly bodes well for our progress.

Correctives are desperately and quickly required, if the country and individuals are to fulfil ambitious goals.

Kiran Karnik is an independent strategy and public policy analyst. His recent books include eVolution: Decoding India’s Disruptive Tech Story (2018) and Crooked Minds: Creating an Innovative Society (2016). His latest book, Decisive Decade,is on India in 2030.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!