ANITA ANAND

I worked in Afghanistan from 2004 till 2016 on short assignments with the UN system and national and international CSOs (civil society organizations), designing training modules for journalists, conducting training, doing evaluations and assessments of projects, and assisting CSOs with strategic planning. I met Afghan homeworkers, cleaners, cooks, drivers, translators, students, ministers, government officials, antique and kilim sellers, donor agency staff and expats. And people on the street. As an Indian I moved around rather freely till 2012 and later 2016, when my movements were further restricted, due to security concerns.

During these two decades, Afghanistan moved from an area of darkness — being in conflict for decades, occupied by the Soviet Union from 1979 to 1989 and under the Taliban from 1996 to 2001, with a civil war in between — to a modern nation state.

The Taliban have taken over a very different Afghanistan from 2001, when they were ousted. In 2004, a 500-person Jirga (gathering of elders) adopted a Constitution forming the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, based on democratic principles. It was a first for the country.

The Constitution recognized civil society as an essential pillar of democracy in Afghanistan. As a new nation, systems had to be put in place for the functioning of CSOs/NGOs. They had to be registered with the Ministry of Economy (MoE). In 2018, according to the Directorate of NGOs of the MoE, 1863 NGOs were registered, implementing 2,537 projects with a total cost of $876 million. Sixty-nine percent of the projects, with budgets amounting to $603 million, were implemented by national NGOs, employing 85,000 persons, and around 1,000 foreign nationals.

In some ways, CSOs as we know them are not new to Afghanistan. Researchers Mehreen Farooq and Waleed Ziad point out that for centuries, the backbone of Afghanistan’s civil society has been its community-based shuras (councils), jirgas (tribal assemblies of elders), and religious institutions. The latter include mosques, madrassas, khaniqas (Sufi centres for cultural and spiritual advancement), and shrines — all key public spaces, in rural, urban, or tribal settings. Mosques, like the Jami Masjid of Herat, have for centuries addressed community concerns and conflicts. In 2006, while I was in Kabul, riots broke out and a week-long curfew was in force. The Imam of the Pul-e-Kshisti mosque in his Friday talk pleaded for calm and peace.

Despite modern governance systems in place, surveys indicate that most Afghans perceive traditional dispute resolution mechanisms to be fairer and more effective than the modern state courts. Newly formed CSOs, recognizing this valuable resource, worked with religious, tribal, and youth leaders to improve their efforts. In Kunduz province, which is prone to ethnic tensions and Taliban violence, CSOs have worked with jirgas, providing them training in anger management and mediation skills to mitigate conflicts in their communities.

Though most of these tribal and religious norms, institutions and community-based organizations tend to be rather conservative, even reactionary, they undoubtedly constitute an important asset in ensuring ‘good governance’ in rural Afghanistan — though there are some that, far from positively promoting good governance, undermine it through pursuit of their sectional interests.

And CSOs are often suspect. Many Afghans blame the suffering and the upset they have endured on alien ideas, foreign weapons, money, and the foreigners who accompanied them. The CSOs are mostly foreign-funded and bring systems that are alien to traditional Afghan values. Transparency, human rights, and rights of women, youth and minorities are contentious issues in Afghan society which is traditionally a tribal and non-inclusive society, patriarchal and hierarchical.

So much so that, since the Taliban took over in August this year, calls for inclusiveness in the government and for protection of women and their rights are falling and will fall on deaf ears, as the Taliban are intent on a strict enforcement of Sharia, which has no room for this inclusion or recognition of rights.

Mainstream media analysts have, since 15 August, focused on how the US involvement in Afghanistan, in trillions of dollars, has been for nought. Nothing could be further from the truth. My experience is quite the opposite. Since 2004, I have witnessed a nation change and grow, mature and bloom. Not everything has gone right, but not everything has gone wrong either. And much of this change has been possible by foreign donor funding, to lay the foundations of a democratic and modern state.

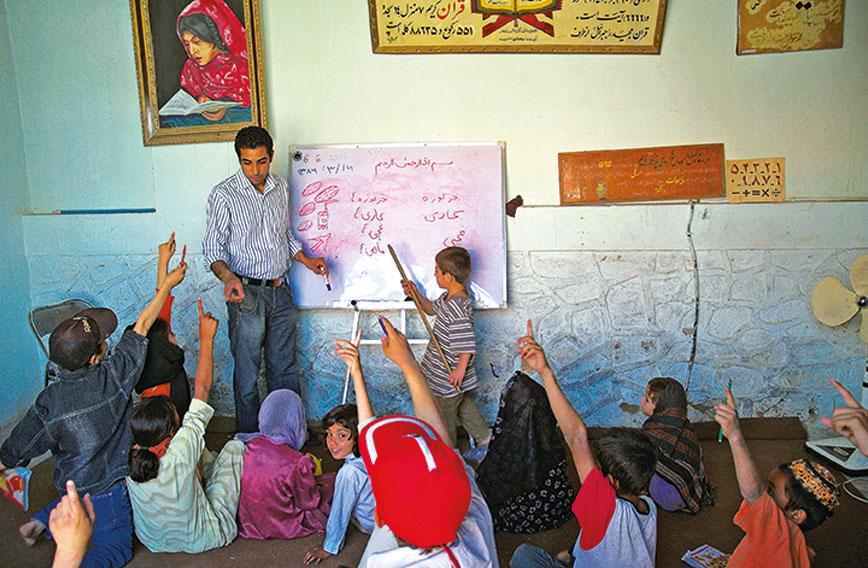

Perhaps the best success story has been the blossoming of CSOs. Women’s organizations, many under the umbrella of the national Afghan Women’s Network (AWN), have successfully lobbied for policies and programmes to mainstream women into Afghan society, focusing on empowering women at the community level, which traditionally has been a male prerogative.

In 2009, during the general election, the AWN initiated the five million women campaign to get women to register to vote. To counter the high rate of domestic violence, women’s groups have initiated shelters to provide a safe space and offer skill development. One shelter in Kabul even opened an all-women’s restaurant a few years ago.

Like women’s organizations, the media too has blossomed. Private and government print and AV media are in all 34 provinces. Social media has been a boon for CSOs to meet, organize campaigns, strategize and lobby the government. On a 2012 visit to Kabul, I met representatives of CSOs from various constituencies —youth, women, minorities, physically challenged, and so on. I heard their concerns and felt that the challenges they faced were no different than in other developing countries, including India. The anxiety over funding, increasing control by the government and lack of capacity plagued many CSOs. The lack of experience and exposure was a hindrance to many CSOs being more effective.

As security concerns increased over the past few years, the government came down on CSOs, with restrictions and arbitrary reporting and financial requirements. In July 2020, Amnesty International warned this development was a “serious threat to the existence of civil society”. The International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law reported that as of January 2021, the MoE had deregistered 3,371 NGOs since 2005 because they could not report to the ministry. As of January 2021, the Ministry of Justice too had terminated 1,600 associations for similar reasons since 2013.

The takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban does not bode well for institutions, including CSOs. However, the foundations established by CSOs cannot be dismissed that easily. How this will play out in the future is yet to be seen.

Anita Anand is a development consultant and author of Kabul Blogs:

My Days in the Life of Afghanistan

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!