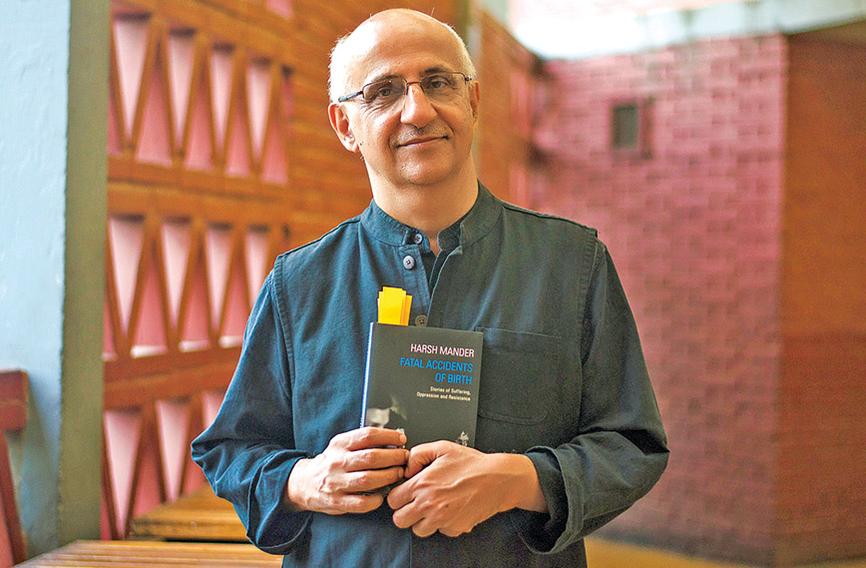

Harsh Mander: ‘For some people, life itself is a curse’

What battered Indians say

Anita Anand

Harsh Mander’s collection of stories is by no means a reader’s delight. Nor are they meant to be. Rather, they are a window, an intimate one, into the lives of boys and girls, men and women, families and entire communities who are born into and live on the margins of Indian society.

Through no fault of theirs, but by being in the wrong place at the wrong time, they have lost their lives, been attacked, molested, raped and burnt, their meagre belongings lost in the blink of an eye, taunted for being Dalits, Muslims, Sikhs, poor, unlettered and just being.

Mander dedicates the book to Rohith Vemula, a Dalit and doctoral candidate at Hyderabad University who committed suicide in 2016. He takes the title from Vemula’s letter which said, among other things, ‘…. some people, for them, life itself is a curse. My birth is my fatal accident.’

Mander is not an armchair writer. After a career in the Indian Administrative Services, he systematically began to work with survivors of mass violence and hunger, with the homeless, including street children. He and his colleagues have actively worked with the underbelly of the marginalised in India.

So, who are the people featured in the book? Naseeb, who was widowed when her entire family was wiped out in the aftermath of the Godhra massacre in Gujarat in 2002 and relocated in a colony for widows and their children. Krishna Gopal, a Dalit from Rajasthan who decided to build a Hanuman temple, as Dalits were not allowed to worship in the village one, and was boycotted and hounded out of the village, along with his family. Not surprising.

There is Sushila in Bengaluru, who was infected with HIV/AIDS by her husband, and her struggle to raise her two children. And other stories of children and adult men, women and transgenders who are reduced to begging and homelessness on the streets and rounded up by police, beaten and locked up. The institutions for orphans and homes for the destitute and mentally challenged are places where care is a distant word.

Underlying the stories in the book is a thread of failure and neglect — of governance, law and order, religious and educational institutions and community — that have turned their faces away from the suffering of those disenfranchised in society. Not only have they turned away, but often actively inculcated hate and intolerance — of Muslims, Dalits and the less fortunate.

While India may have a quota system for minorities and Scheduled Castes in educational institutions and government jobs, they are still treated as less than equal by Indian society. Laws on paper cannot change hearts and minds.

The stories, while depressing and sad, also show the resistance and resilience of the protagonists. Being beaten down is not in their vocabulary. Mander not only shares the stories as stories but also how human rights activists, lawyers and civil society organisations have stepped in to help bring about justice, and help people, difficult as it may be.

Reading the stories, I cannot imagine middle-class and privileged Indians coming close to overcoming the adversities of the poor and marginalised among our midst. Our sense of entitlement ensures that through connections, money and patronage, we do not suffer. In our blindness to those less privileged around us, we immerse ourselves in acquiring wealth, property, leisure and luxury. But, as it is said, the poor will always be amongst us.

For those who are in the NGO sector, the stories may not be new. Yet, some lessons can be learned. In one story Mander asks that we withhold judgement. A couple gave their daughter to a community person who offered to take care of her. In return, he paid off their debts. A police report was filed against them and the daughter was brought back to them. Four months later she died. The couple didn’t have enough to feed her. Would she have been better off in the home of the person who offered to raise her? We’ll never know.

Anita Anand is a development specialist and author of Kabul Blogs: My Days in the Life of Afghanistan.

Comments

Currently there are no Comments. Be first to write a comment!